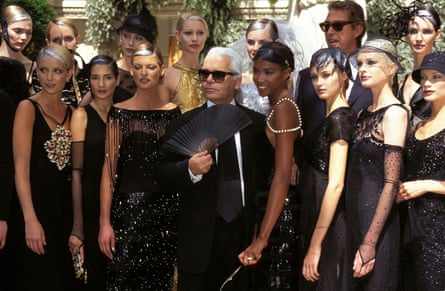

Costume historians will doubtless look back on the day Karl Lagerfeld died in February 2019, leaving in his will lavish instructions for the ongoing care of his Birman cat Choupette, as the precise moment when the fun finally went out of high fashion. Yes, it’s possible another full-blown eccentric will one day preside over a big house. But it doesn’t feel, in the era of the global conglomerate, terribly likely. “Creation,” as Lagerfeld once put it, “is not a democratic process.” The more people (I may mean accountants) who stick their oar in, the more likely we are to get half a dozen good camel coats on a catwalk than the kind of show, raffiné but wildly exuberant, that could reduce the late André Leon Talley, of American Vogue, to tears of joy. The cape-clad, fan-carrying, monocle-wearing, be-ponytailed Lagerfeld was the last of the last and he deserves a serious biography.

Does Paradise Now: The Extraordinary Life of Karl Lagerfeld do the job? Or is it, like a toile, only about halfway there? William Middleton, its author, certainly has the fashion chops: he used to head the Paris bureau of Women’s Wear Daily. But the trouble with insiders is that their respect is usually too ardent, and their need to remain on good terms with their world’s big names too powerful, for the distance required of biography. Yes, he gives us in its entirety the long reign of Kaiser Karl, from his peculiar childhood in Germany to the lonely months at the end when he was secretly fighting cancer, leaving out – or so it feels – not a single one of the parties he threw along the way.

Among his interviewees are the designer’s muses Inès de la Fressange, with whom Lagerfeld famously fell out, and Amanda Harlech, whom he pinched from under the nose of John Galliano. He even gets to the heart of Lagerfeld’s bizarre relationship with the love of his life, Jacques de Bascher, a French dandy who died of an Aids-related illness in 1989 (and who cheated on him with Yves Saint Laurent). Somehow, though, he makes rather a dull job of it all. The book wants for something that its subject, who liked to drink Coca-Cola in Lalique goblets, knew all about: vulgarity. In this case, the vulgarity involved in seeking out enemies as well as friends, and in casting a droll eye on the ridiculous, the stupid and the frequently obscene.

Lagerfeld was born in 1933 to polyglot parents who forced him to read Goethe as a boy. His father had made his money in condensed milk; his mother was a one-time member of the Nazi party – a photo exists of a four-year-old Karl standing in front of a flagpole at the family’s country estate near Hamburg, at the top of which flaps a swastika – who often treated her son with contempt. “Your nose is like a potato!” she liked to tell him.

Lagerfeld, though, was not one to cry in a corner. At four, he asked if he might have a valet for his birthday. By the time he was 19, he’d left for Paris, where soon after his arrival, he won the Woolmark prize for his design for a “cocktail coat” (it had three-quarter sleeves, patch pockets and – here was the minor revolution – a plunging neckline at its back). Thanks to this, he was soon apprenticed at Balmain, and from there everything else followed. In 1958, he joined Jean Patou. In 1962, he began designing for the up-and-coming Chloé. Three years later, he was also working for Fendi. Finally, in 1983, he took over at Chanel. Before his arrival, Chanel had only one boutique, and scent accounted for about 90% of its business. In the course of his 36-year reign, he took it from near bankruptcy to $11bn (£9bn) in sales.

A workaholic, he designed 14 collections most years, including for his own label. But he was also a photographer, a publisher, a collector and a doer-upper of grand houses, his estates extending across Europe to the point where the reader loses track (are we in Cologne or Biarritz now?). Such freneticism often shrouds an inability to be intimate, and the reader senses this in the case of Lagerfeld. The more Middleton describes his elaborate interiors (an early flat had an orange awning “to give guests a good complexion”) and his opulent parties (at a buffet dinner for 900 at his Paris apartments, guests were served by waiters in 18th-century-style white wigs, red breeches and buckled shoes), the stronger the whiff of loneliness grows. “I hate rich people who live below their means,” he said. But perhaps he just hated people – or at any rate, those who came too close.

His relationship with de Bascher, cut cruelly short, was a strange pantomime, possibly sexless, though he was easily Lagerfeld’s match when it came to kitsch. (In 1978, he arrived at a Venetian-themed party hosted by Karl with a model of the Rialto Bridge built across his shoulders and arms, which were sticking out, and thus somewhat impractical in a crowd situation.) A decade into their relationship, Lagerfeld decided that his lover simply must get engaged to a princess – in this case, his friend Diane de Beauvau-Craon, a minor Spanish-French aristocrat. “I paid for everything,” Lagerfeld said. “Which didn’t bother me at all.” The wedding would never take place. By the end of his life, the designer communicated with those friends of whom he was fondest by sending them little messages from his cat Choupette, a beast to whom Middleton devotes an entire chapter.

Still, it isn’t for his heart that Lagerfeld will be remembered, but for his eye. There were, perhaps, more missteps than Middleton allows (he picks out for special opprobrium a neoprene bag for Chanel’s spring/summer ready-to-wear collection of 1998 that was – the horrors! – shaped “something like the headrest of an airline seat”). But he understood the spirit of Chanel, the brocades and the boleros and the pearls, better than anyone else. Metaphorically speaking, he determinedly unpinned the client’s immaculate chignon. His updates, playful twists that spoke of fun as well as of taste and money, were delightful, even if he wasn’t – and even if no one but an oligarch could possibly afford them. He saw the future, and it was paved all over with logos.