Images and Article from theconversation.com.

In this new series, Remaking History, academics take a look at the ways they are recreating historical practices, and how this impacts their research today.

Although I have been sewing as a hobby for many years, making and wearing historical clothing was not something I imagined myself doing when I first began researching the history of corsets and hooped skirts.

But many years on – and many corsets later – the experimental process of reconstructing 400-year-old garments has taught me many things about historical making practices, women’s experiences and about not believing everything you read.

In my research, I look at women’s clothing from the 16th and 17th centuries. There are very few sources from this time where women themselves describe what it was like to wear “bodies”, “stays” and “farthingales” – the names given to corsets and hooped skirts at the time.

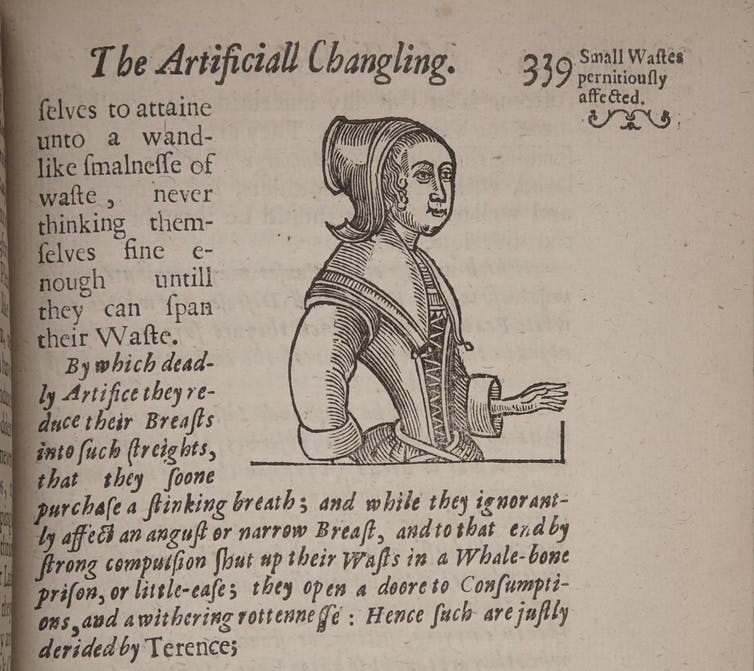

The philosopher Michel de Montaigne portrayed these garments as torture devices women used to become slender, reflecting their inherent vanity.

Other men blamed women for deforming their own bodies and that of their children, for causing infertility or miscarriage, and even for hiding sexually transmitted infections.

Wellcome Library London

Yet, in the face of these criticisms, corsets and hooped skirts went from being elite garments worn by a few aristocrats in royal courts to common among many different classes of women in Europe. During the 17th and 18th centuries, women led the way in purchasing these garments and in dictating to their tailors what they wanted and why.

Despite the demonstrated popularity of this clothing among women, many myths persist. Without physical or historical proof to interrogate whether these garments were as restrictive or painful as they were made out to be, such myths are hard to overcome.

This is where reconstruction comes in.

Read more:

Remaking history: how recreating early daguerreotype photographs gave us a window to the past

Reconstructing early corsets

My work follows other approaches that have reconstructed surviving historical clothing.

I focus on making my corsets to the patterns and dimensions of surviving garments.

Sarah A. Bendall, Author provided

All my corsets (except one) were completely hand sewn using techniques and stitches visible in the originals.

For many of the reconstructions I kept an online diary of the making process, noting both my successes and failures as I attempted to replicate the work of master craftsmen with many more years of experience than myself.

Reconstructions of historical garments can never be exact replicas: it is always an act of interpretation. Informed compromises between modern and historical materials are necessary.

All my reconstructions are made from natural fibre fabrics that were available in the past such as silk and linen, but differences in modern fabric manufacturing make it impossible to precisely replicate historical fabrics.

Historical corsets often got their shape and stiffness from whale baleen. Commercial whaling was banned in 1986 and so I used modern synthetics specifically designed to mimic the properties of baleen.

Despite these challenges, making historical corsets taught me to think like a tailor, to understand why specific materials or techniques were used and to assess the artisanal making knowledge that we have lost.

Lessons in the wearing

Once the corsets were made, it was time for them to be worn. I both wore them myself, and observed other women in them.

Sarah A. Bendall, Author provided

I instructed models to sit down, bend over and reach up to test the ways these garments limited or impeded movement. I found corsets spanned a wide spectrum of comfort and restrictiveness depending on the design of the garment: the cut, the length and how much it was boned.

Early modern corsets could be uncomfortable if not fitted to individual measurements or made correctly. This shows the importance of well-tailored garment in times before modern off-the-rack standardised clothing made from stretch fabrics.

Most 17th-century garments are front lacing, giving women control over how they wore the garment at different times of the day. A woman could wear it loose or tight laced. She may also have worn it every day or only for formal occasions.

Sarah A. Bendall, Author provided

My experiments also showed the slenderising effects of these early corsets observed by Montaigne were largely due to the optical illusion of their cylindrical shape. My corsets didn’t reduce body measurements by much. I found the most restrictive feature of 17th century corsets to be their off-shoulder straps that limit arm movement, but this is not something unique to corsets.

One of my reconstructions was a maternity corset from the late 17th century. Placing it on a model with a simulated pregnancy bump showed how the design accommodated pregnancy: it supported the breasts and back, while not restricting the abdomen. This is far from the picture painted by sensationalist male moralists that warned of the dangers to pregnancy.

Sarah A. Bendall, Author provided

We may never know precisely how a 16th or 17th-century woman felt when she wore a corset, nor exactly recapture her bodily experiences. However, reconstructions can help us to assess how much written sources do or do not reflect the lived experiences of historical women – and go one step further in showing how many myths about early corsets written by men are exaggerations.

Read more:

Long before Billie Eilish, women wore corsets for form, function and support

Article shared from theconversation.com