Browse the site of a retailer like Revolve, and whether you realise it or not, you’ll probably see inventory that’s there because an algorithm decided it should be.

Fashion businesses haven’t only been leaning into AI to make smarter forecasts. A number are also embracing a data-driven “test-and-learn” approach, where they produce small batches of goods and then use algorithms to quickly crunch the data on top performers to reorder. Those reorders and tasks like distributing items to the right stores and warehouses can even be automated, helping brands push the speed limits set by their supply chains.

It’s like a tech-forward version of the model pioneered by Zara more than a decade ago and supercharged more recently by Shein, but even brands at higher price points and in categories other than clothing are leaning into variations of the approach to minimise their inventory risks.

Revolve has said this read-and-react model helped it weather the pandemic-induced disruptions in the market and in supply chains that have hampered some of its competitors. The company highlighted it as a major contributor to its growth in sales and profits in 2021.

“Since we have automated so many aspects of the decision-making process, we can leverage data much faster than others to identify trends and make merchandising decisions in a very quick, accurate and efficient way,” co-founder Michael Mente told investors in February.

At Lulu’s Fashion Lounge, an online retailer that does much of its business selling items like $100 event dresses, 70 percent of sales in the six months through July 2021 came from reorders of items it previously tested in small batches, it revealed in its filing to go public last year. David Creight, the company’s chief executive, told investors last week while discussing the company’s latest quarter, which saw it raise its full-year outlook, that “algorithmic driven purchasing” accounted for 70 percent of its revenue.

“There’s been a transformation more broadly in terms of the merchant business model and rethinking the infusion of data science into inventory planning and analysis,” said Oliver Chen, a managing director and senior research analyst at Cowen.

Executing this model can be harder than it first appears since it requires having the fabric and materials available to quickly reproduce orders and a fast-moving supply chain to manufacture and distribute items.

But brands have strong incentives to make it work, especially in recent months. After two years of being able to keep stock lean, many brands are seeing inventory pile-ups again. With inflation also making consumer spending less predictable, they’re seeking to be smarter and faster in matching supply to demand.

Companies able to put the model to use can reap benefits like freeing up capital, since less of it is tied up in large inventory orders, and importantly, selling more items at full price.

A Data-Driven Model for Merchandising

Online, direct-to-consumer retailers like Revolve and Lulu’s are arguably best-suited to operating this way since they can put a small number of units online and immediately start to see how customers are responding. Chen has noted in his research on Revolve that it will buy on average about 50 units of a style, and then the company’s proprietary dashboard automates reorders by considering click-through, browsing behaviour and conversion data.

In an interview, Chen said these companies tend to be more agile and have different organisational structures than legacy retailers, too. Though even companies like Macy’s are moving to be more agile by removing unnecessary layers in their decision-making, he added.

The DTC footwear brand Rothy’s is able to decide whether to order more units within 48 hours of an item being live on its e-commerce site, Erin Lowenberg, the company’s senior vice president of merchandising and product, told BoF. The company isn’t yet using AI to make the decisions, she said, but it keeps a close watch on indicators like sales, shopper behaviour and activity on social media to decide whether to invest more in a product.

It can also use the information in other ways. If one shoe silhouette is selling well in a particular colour, Rothy’s can introduce that colour in another shoe style, or in a handbag.

Rothy’s has an advantage in that it owns its factory, giving it more control over its production than most brands. It also makes everything with the same recycled plastic yarn, so having the right materials on hand typically isn’t an issue.

But it’s not only companies like Rothy’s and Revolve putting the model to use.

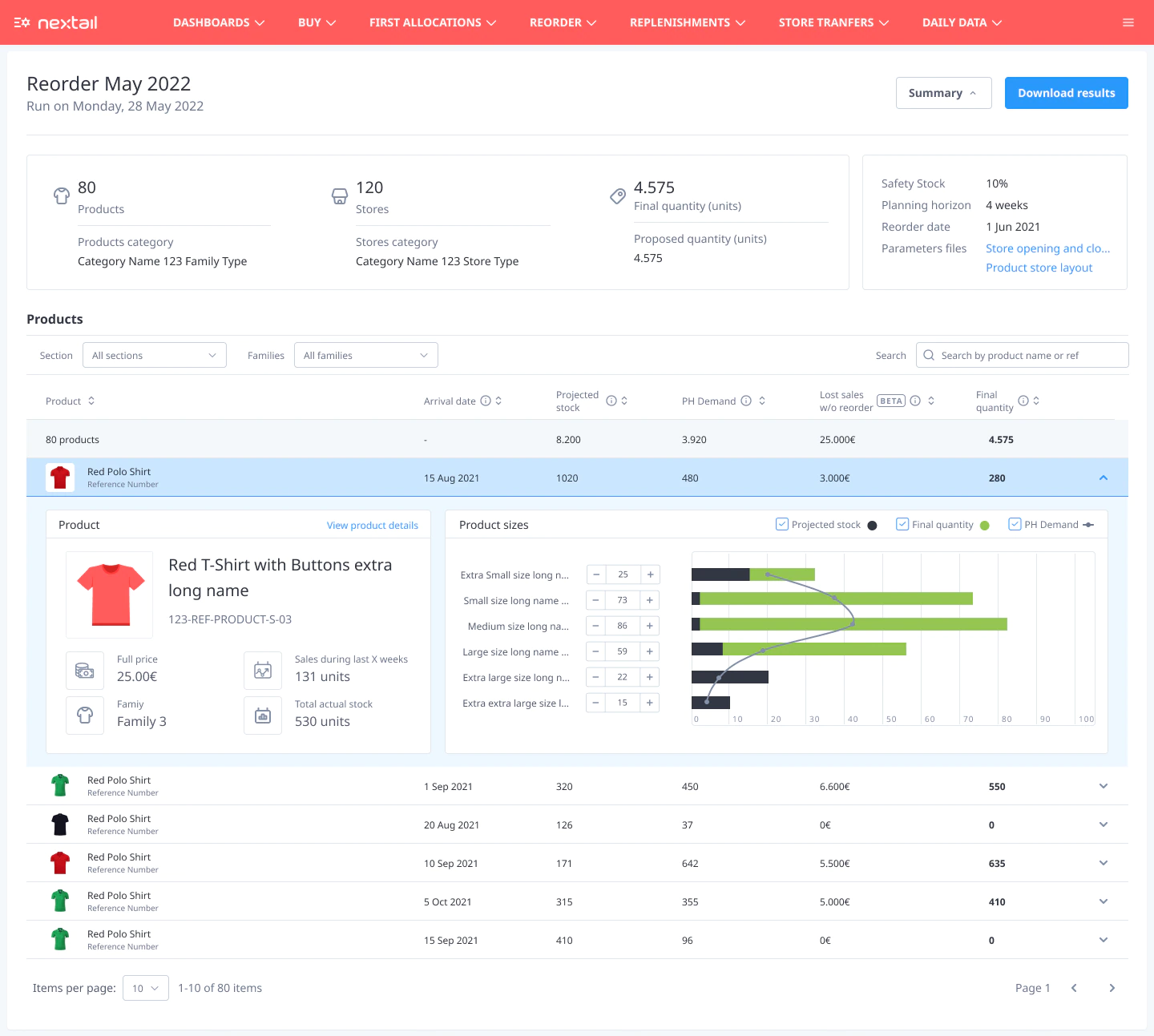

Guess and Spanish jewellery brand Aristocrazy have started using a newly introduced feature for fast reorders from Nextail, a data-focused merchandising platform, according to Nextail’s chief revenue officer, Brian Crain. Companies like these may move at different speeds in restocking inventory, but the point of Nextail’s reorder feature is to allow them to be quick enough to restock within the same season, Crain said.

The platform monitors transactions and behaviour at the level of individual items across a brand’s stores and uses predictive algorithms to forecast demand. Nextail typically counsels clients to measure performance for at least a week to make sure there’s enough data to draw statistically valid conclusions. Its platform also automates decisions that would have traditionally been handled by a team using Excel spreadsheets or similar software.

“Think about Guess or a company like that with 1,000 stores all over the world,” Crain said. “Because technology is in such a place that we can leverage scalability and AI, we can automate the decisions in terms of what SKUs in what quantities go to what stores.”

Risks and Rewards

In their disclosures to investors and in earnings calls, Revolve and Lulu’s have both called out what proponents of this type of merchandising say is one of its biggest benefits: more full-price sales.

“Illustrating the efficacy of our data-driven merchandising, in 2021, approximately 87 percent of our net sales were at full price, which we define as sales with a price of not less than 95 percent of the full retail price,” Revolve said in its report of its full-year results.

At Lulu’s, of the 70 percent of sales from reorders in the first half of 2021, 94 percent were sold at full price, it said in its filing to go public.

Because they’re reordering styles they already know are in demand, retailers should end up with less leftover inventory that needs to be marked down. That keeps margins healthy, which is “just core to driving profitability,” Chen said.

Both Lowenberg and Crain said there’s also a sustainability benefit as there’s less waste when supply more accurately matches demand.

There is, however, a risk in small-batch testing. If a company produces too few units to start and the product sells well, stock can run out. When that happens, it leaves money on the table and customers dissatisfied. It’s an issue Lulu’s has struggled with, according to Chen.

“It’s had a lot of stockouts, and that’s negatively impacted customer satisfaction,” he said but added he’s optimistic they’ll eventually solve the problem.

Lulu’s declined to be interviewed for this story.

While Rothy’s always makes sure to have stock in its core styles, outside of those items it can be a challenge at times to ensure the right stock is available, Lowenberg explained.

“It is the constant battle,” she said. “Scarcity in inventory is a good thing when we have the ability to move really quickly. It’s something we have to hold hands-on and know it’s ok if something sells out because we actually have the next better thing coming.”

And given the choice of problems — to sell out of an item or end up with too much left over — most companies would probably choose the former.