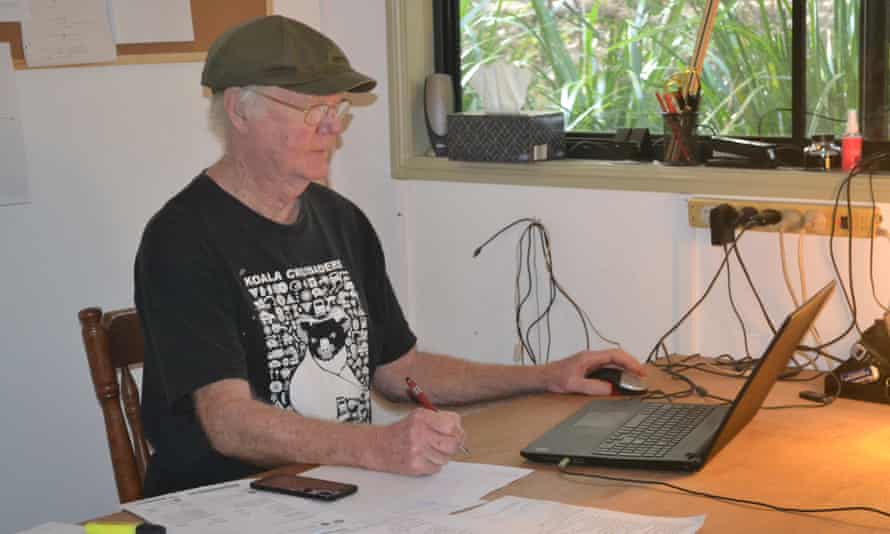

The NBN rollout may have been completed, but Richard Proudfoot is still using an old ADSL internet connection, and he has to juggle his Zoom meetings around his partner’s work.

He runs a small IT business from his home in Maleny, on the Sunshine Coast, about 100km north of Brisbane, while his partner is a part-time university lecturer.

Due to their property’s terrain, NBN Co has told him he is not able to connect to fixed wireless or fixed line. While he has the option of satellite, many users have reported poor speeds and reliability. He has stuck with ADSL for the time being because he believes the tree cover and weather would adversely effect his service.

“We are very, very dependent on a reliable internet ADSL connection. To make it work for us given the limitations, we schedule internet use based on need … we cannot do concurrent Zoom meetings so we rearrange diaries in order to cope.”

The Coalition and NBN Co declared the rollout of the then $51bn network complete in 2020. There are now 12.1m homes able to connect, and 8.5m homes on the NBN.

The high-speed network was meant to resolve the digital divide in Australia, but two years on from its completion there remains a stark difference between the haves and have-nots; those who have a decent internet service and those still waiting or suffering from poor speeds and reliability on their NBN service.

The Liberal MP Julian Leeser wrote a scathing review of the NBN in a submission to the federal government’s regional telecommunications review last year, describing it as “too slow with countless delays”.

Leeser’s northern Sydney electorate, Berowra, is a mix of suburban and semi-regional locations, meaning his constituents are living with the spectrum of NBN technologies, from fixed to wireless and satellite.

“There is too much variability in the quality of coverage across the various NBN technologies,” he said.

The pandemic forced many people to work from home and rely on their home internet more than ever before.

Leeser said that teachers had been forced to work out of McDonald’s car parks to leech the wifi for online classes, people were unable to work from home or undertake telehealth appointments, and some had even been forced to move out of the area due to their poor NBN connection.

Sign up to receive the top stories from Guardian Australia every morning

Unlike the 2010 and 2013 elections when the NBN rollout was a hot topic, it has yet to grab the headlines this time around, but it appears it is still front of mind for some voters.

Many Guardian Australia readers raised problems with the project when asked what their major concerns were ahead of this month’s federal election.

One reader, Cate, who lives in Killarney Heights in the Sydney electorate of Warringah, missed out on full fibre or cable that some nearby suburbs have access to.

She says she was originally connected via the Optus internet cable but was moved over to fibre-to-the-node (FttN) on the NBN.

“Using Optus cable we rarely had dropouts. I could count on one hand the number of times over five years that we lost internet for any noticeable length of time,” she says.

Now she says they experience daily interruptions.

“Our modem takes five to 10 minutes to reconnect so this can often mean at least 25 to 50 minutes a day of disruption to our service and this is still considered acceptable by NBN and they will do nothing to fix it.”

She says she is rarely able to get the top speeds promised. In speed test results Cate provided to Guardian Australia taken between 2pm and 3pm on a weekday, the results ranged from 1.3Mbps to 40Mbps, compared to 100Mbps on her previous Optus cable.

Where to from here?

The communications minister, Paul Fletcher, argues it would not have been possible for so many people to work from home during the pandemic under Labor’s original NBN plan..

“If we had stuck to Labor’s plan, when the pandemic hit and millions of people moved overnight to working and studying from home, Australia would have been in a terrible mess,” Fletcher said in a CommsDay Summit speech this week.

Fletcher’s argument, however, is based on modelling undertaken in 2013 that NBN Co’s current management has since distanced itself from.

In late 2020, the Coalition announced $4.5bn in upgrades to 8m premises to get speeds of up to 1Gbps by 2023, including 2m homes on FttN. Around 100,000 premises can now order these upgrades – provided they agree to pay for a higher speed service.

There is also a $750m upgrade to wireless announced in March as part of a $1.3bn regional communications package which will also allow more people on satellite to shift to wireless and free up space on the satellite service.

The Coalition is also funding upgrades through the Regional Connectivity Grants program. Many of those grants upgrade whole towns in regional areas from satellite to full fibre to the premises. However, as Guardian Australia has previously reported, two grants in the first funding round were given to upgrade a single business to full fibre in the New England electorate.

Leeser told Guardian Australia he believes his community’s concerns with the NBN would be addressed through the wireless upgrades and opening up the grants program to semi-urban areas such as Kenthurst and Dural in his electorate.

Labor is promising to match the spending, but go further. It has conducted detailed modelling of the rollout and determined 1.5m more homes can be upgraded to full fibre, at a cost of $2.4bn. It will mean seven out of eight FttN premises would have access to upgrades by 2025.

The shadow communications minister, Michelle Rowland, said too much had been wasted by the Coalition downgrading the NBN from full fibre, only to backflip with the planned upgrades now, costing $58bn.

“This is $29bn more than what the Liberals said it would cost – double the original promise – yet delivers less than the original fibre plan,” she said in a speech this week.

“What Australians want is more reliable and faster connectivity.”

Fletcher dismissed the plans as “vague” and targeted only at marginal electorates.

Whoever wins, it will be a race against time. Around 119,000 premises that are connected to the NBN via FttN still can’t get the minimum 25Mbps download and 5Mbps upload speeds. Due to the ageing copper and environmental conditions, FttN connections will continue to get worse over time.

In February, the NBN CEO, Stephen Rue, admitted the bit rate – the number of bits that can be transferred across the network per second – would degrade between 2% and 4% every year on average across the 4m FttN connections.

The other looming factor is people switching the NBN off. Customers frustrated with the NBN might look to 5G or another service like Elon Musk’s Starlink, and threaten the ability of the network to make a return on the taxpayer investment.

In the Sunshine Coast, Proudfoot has not reached that point yet, partly because the transfer of customers from satellite to fixed wireless could benefit him and partly due to the cost of Musk’s Starlink.

“This is galling because as taxpayers we have all paid to have a universal, reliable internet connection and we haven’t got it. Instead, with after-tax money flowing directly to a US billionaire, we are paying twice for ultimately what is still an inferior product.”