The most memorable collection of clothing designed by John Bates, who has died aged 87, had just 35 garments plus a few inspired accessories, all of which could be put together into unrepetitive combinations. It was designed very impromptu in 1965 for an imaginary wearer – Emma Peel, heroine of the television series The Avengers, played by Diana Rigg – and deserves all its many entries in style histories for its high concept, and for marking a major change in fashion.

Bates’s great commission nearly did not happen. The wardrobe of the previous Avengers lead actor, Honor Blackman as Cathy Gale, had been created for the earlier series by Frederick Starke, an establishment designer of womenswear. Blackman’s clothes mixed an old-movie glamour with Paris Left Bank beat fashion, including long boots; for fights, she was clad in heavy black leather.

Female viewers responded to the beat outfits, and a few copies were tentatively marketed. Male television executives were more excited by the leathers, and when in 1965 the show’s parent company, ABC TV, proposed to shoot a new series not in grey video but in black-and-white film, for distribution in the US, its buyers insisted that Blackman’s replacement should retain them. The casting choice was Rigg, a decade younger, and also taller, rangier and larkier, than Blackman.

All those involved realised that the costume design, even the leathers, had lost their edge in the 18 months between series, and felt dangerously genteel. Anne Trehearne, then fashion editor of the glossy magazine Queen, was urgently called in for a restyle. She recommended Jean Muir, whose label, Jane & Jane, was popular among well-off young people for its cleverly cut dresses. Muir accepted, but could not meet the show’s deadline. Bates had a label, Jean Varon, for the same sort of customer base, and in four days he came up with a strong theme for Emma Peel – mostly black-and-white graphics to capitalise on the monochrome filming and the current chic of op art.

He used inexpensive synthetics such as PVC and stretch fabrics, as well as furs and lace, to fill the capsule wardrobe head to toe, from a beret appliqued with a bullseye target to striped tights, added trouser suits – then fairly new for women – and above-the-knee skirts, cut away the shell of the fighting suit and popped a soft blouse beneath. (Although Bates persuaded Rigg to lose weight the better to display his designs, he emphasised her non-model shape.) Trehearne defended him against US backers panicked by minis and bare midriffs; and he cut and finished Rigg’s skirts precisely to their intended length, so there was no hem that could be let down.

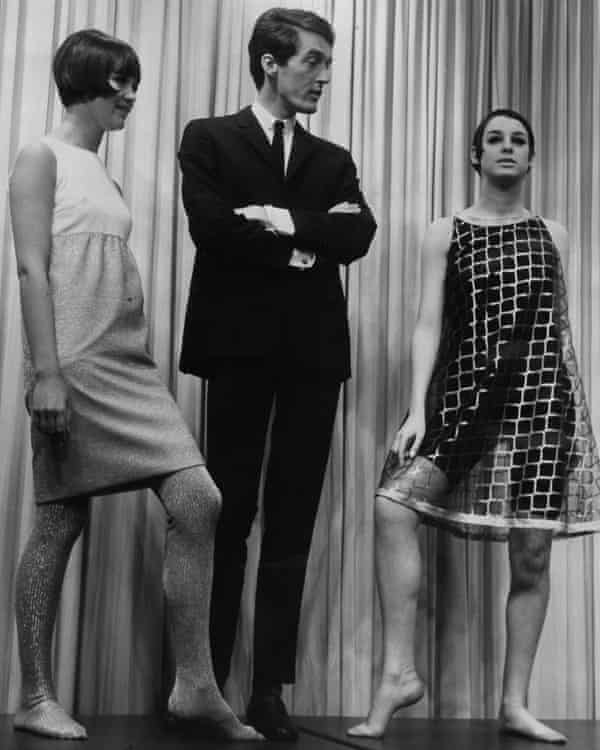

Trehearne staged the show’s press launch and promotional pictures as a fashion show, so the publicity promoted Bates’s decision to license British manufacturers to make a range of the clothes and accessories for a young, middle-price, audience. (Kangol’s target beret cost 19s 11d.) The original clothes – they were wearable clothes, never “costumes” – were on screen for only the 26-episode series, but Bates’s look remains the encapsulation of fashion’s mid-1960s turn to youth, media and the UK.

Bates began his life’s interest by sewing little dresses out of his mother’s dusters, and drawing frocks for her that she would never own, though he did give her, at her request, an op art fur coat for Christmas in 1965.

He and his two hearty brothers were sons of a miner in Dinnington, Ponteland, near Newcastle; unlike his siblings, he was a keen reader, and intended to be a journalist. He left school at 15, learned shorthand in the hope of a job on a Newcastle newspaper, failed, and left for London, where he then did his national service in the War Office.

He showed the old sketches to friends, who secured him an informal apprenticeship with the fashion designer Herbert Sidon. Sidon’s Sloane Street salon was known for debutante ballgowns and stage outfits. Bates learned from Sidon that clothes for theatrical or film leads need a single, easily grasped, concept that is best expressed as a silhouette.

After minor adventures elsewhere in the rag trade, Bates was funded by investors who had given up on Sidon ever supplying boutique merchandise; his label Jean Varon had a difficult start, supplying wholesale dresses to the department store Fenwick, before the upmarket fashion chain Wallis commissioned a complete collection. Bates’s ever-shortening, simple, indeed child-like, tubular dresses were endorsed by the fashion editor Marit Allen, first at Queen magazine and then in her Young Idea section of Vogue: they were as far as possible from the boned-bodice cocktail frocks of the recent past.

Bates did not like the restrictions of film work – so many versions of the same garment for the stunts – and after the Avengers venture returned to his Jean Varon dress label, with a later supplementary label for tailoring. He was successful through the 60s and 70s at dramatic, single-idea outfits for special occasions (wedding dresses for Cilla Black, and for Allen, white gabardine trimmed in silver vinyl) and for film and stage performances (Dusty Springfield, Cleo Laine, Julie Christie, Elaine Stritch, Maggie Smith), plus Princess Margaret on holiday. His all-concealing, all-forgiving, ground-sweeping 70s gowns could create character – even as worn with the wrong attitude and accessories by Penelope Keith’s nouveau Margo Leadbetter in the television comedy The Good Life.

Bates moved into couture in 1974, appreciating the freedom it gave him to work with skilled crafters in fine materials, but the business went bankrupt in the early 80s. His last enterprise, the Designer Club, was for large sizes, before he retired in 1990 to Llansaint, Carmarthenshire, to paint, occasionally creating a dress for a favoured client. The Museum of Costume (now the Fashion Museum) in Bath held a retrospective of his work in 2006.

He is survived by his partner, John Siggins.