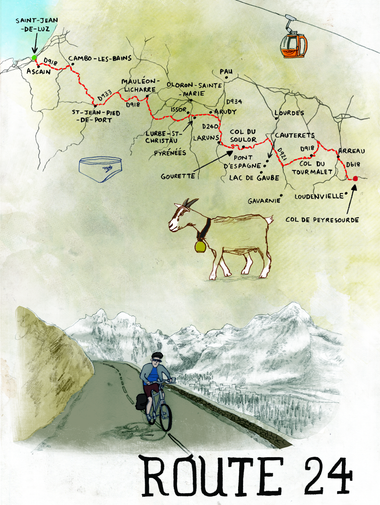

Route Thermale

Start Saint-Jean-de-Luz

End Col de Peyresourde

Distance 217 miles

Allow 4-5 days

I came across the Route Thermale on an old, dog-eared map while trying to find a coherent route across the Pyrenees. Scanning the winding mountain roads I noticed, in tiny print, the words “Route Thermale” against the D918. I was intrigued. I turned to my phone and discovered that the route was financed by Napoleon III to join up the spa towns across the mountains – a perfect “slow road” adventure. My map had it marked as being “scenic” for almost its entire length, and it wasn’t hard to see why.

Starting on the Atlantic coast at Saint-Jean-de-Luz, it takes in the highest passes in the Pyrenees, wooded valleys and picturesque villages, as well as thermal baths, passing close to some of the Pyrenees’ best-loved sites: Cauterets, Gavarnie and Pont d’Espagne. The “Route des Cols” is also a favourite for seasoned cyclists, famous for being included in the 1910 Tour de France. My plan was to follow it as far as the border between the Hautes-Pyrénées and the Haute-Garonne at the top of Col de Peyresourde.

Leaving the Basque coast behind at Saint-Jean-de-Luz, the road east winds through wooded hills, the Pyrenees soon rising in front of you, and white-painted, red-tiled villages appear. After Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port things get more hilly – leading to the first of the cols and thermal spas, starting with Col d’Osquich (392m).

With every mile the scenery gets better – forests, hills and valleys at every turn. Col d’Aubisque (1,700m) is next up, with pine and birch forests, hairpin bends and spectacular views. We stop to attempt to cycle the pass (I give up part way up!).

Nerves of steel are needed for the road cut into near-vertical cliffs around Col du Soulor (1,474m). It’s narrow, with a couple of tunnels, so you’ll need to drive it in the afternoon if your vehicle is over three tonnes (east to west in the morning). The scenery is sublime: the valley floor seems miles below – with nothing but a few concrete blocks between you – while impossible peaks loom above. This beautiful section of road is another favourite of diehard cyclists.

Cauterets, a delightful spa town and ski resort, is a short diversion off the D918, but worth a visit (and even an overnight stay). There’s a public spa and hammam, for relaxing in thermal waters in indoor and outdoor pools with views of the mountains, or plenty of hotel spas for massages and treatments, such as the Cauterets Astérides.

A tricky road winds out of Cauterets up to Pont d’Espagne – a tourist hotspot where a stone bridge spans a deep gorge at the meeting of two raging torrents. Take the cable car and then ski lift to Lac de Gaube, a vision of perfection.

It’s now up, up and away to Col du Tourmalet (2,115m), one of the Tour de France’s most dreaded climbs, with a series of hairpin bends (watch out for cyclists). It’s a little spartan at the top, but there are amazing views before the descent and next climb to Col d’Aspin (1,489m).

The route next leads through Arreau, a pretty village with partly cobbled streets, and on to Loudenvielle, a beautiful town in Vallée du Louron. You could follow the route all the way to Argelès-sur-Mer on the Med. But for us the journey is complete once we reach the border between the Hautes-Pyrénées and the Haute-Garonne and the halfway point across the Pyrenees at the Col de Peyresourde. It’s a 30-minute chug from Loudenvielle through beautiful forest on another winding mountain road, where the Tour de France graffiti urges us to “Allez Allez!”. At the top, views to the east and west are incredible.

If you have the legs it must be a fantastic cycle, I think, as we turn and head back down to the village for our reward: a trip to Balnéa Spa (€20 per adult for access to the baths in high season). It’s a wonderful, watery play park with themed geothermal baths heated by hot springs. Swim from the Japanese hot pool to the Mexican cenote or book in for a treatment, but don’t forget your Speedos (the law prohibits shorts in all French pools).

Where to stay

Camping du Valentin, Laruns: great campsite with bar and pool at the foot of Col d’Aubisque (pitch, including van, from €20 for two adults a night).

Aire de Camping-Car, Cauterets: handy for the spa and telecabines to Pont d’Espagne (€11 per van and passengers for 24 hours with services).

Aire de Camping-Car, Loudenvielle: Perfectly placed in the village and very handy for the spa (€14 for one van and passengers for 24 hours with services).

Get there

Bilbao in northern Spain is the nearest ferry port to the start of the route (just over an hour away). Brittany Ferries sails from Portsmouth (two nights). Or travel from Plymouth to Roscoff and drive (about nine hours, 545 miles). The D918 begins at Saint-Jean-de-Luz, but on the way is sometimes assimilated into other roads, so it occasionally changes numbers when bypassing villages.

The presqu’îles of western France

Start Quiberon

End Les Portes-en-Ré

Distance 255 miles

Allow 1-2 weeks

Want sun but don’t want the hassle (and cost) of the Côte d’Azur? Head west and explore France’s “almost islands” on an epic drive that will take you across tidal causeways, gigantic bridges and sand spits to a France that’s hot, charming and, if you want it, a little bit chi-chi. The islands are spread out along the coast from Brittany to just above the Gironde estuary and each is reachable by campervan (or car) via a causeway or bridge. They all have their own unique character, but are unmistakably littoral, shaped by the Atlantic wind and waves. These are the places to buy sun-baked salt, taste ocean-fresh oysters or scrape the mudflats on a big, low tide for a cockle feast of your own.

We start this journey at Quiberon, on the southern side of Brittany, crossing the sand spit to the Côte Sauvage, a wild, west-facing series of coves and rugged cliffs. We swim in the sea while spear fishermen scour the rocks for lunch. A walk around Quiberon, the smart port and beach resort at the end of the island, leads us to swanky restaurants with well-heeled clientele enjoying fruits de mer under parasols.

We head south, on the D781, stopping at Carnac to see thousands of standing stones that are perfectly aligned, like a neolithic landing strip. I’ve never seen anything like it, and can’t quite get to grips with its scale and size, even when we drive away towards Vannes and it’s still going. We skirt Vannes and the Golfe du Morbihan, heading for La Roche-Bernard, a gorgeous, arty town that sits high on a bend above the Vilaine. We wander the narrow streets late at night, spotting ceramic gargoyles made by local potters.

Still heading south we head for Le Croisic, another jolly, geranium-spattered presqu’île with harbourside restaurants and cool streets of gaily painted and shuttered houses. We stop and watch sailing boats as they head off on Atlantic adventures. It’s a great contrast to the seven-mile-long cruise we take next, along the esplanade at La Baule, where modern apartment blocks crowd out the last remaining villas. This is the French en vacances en masse and it’s lively, showy and fun.

We head south, hugging the coast, crossing the Loire on the huge arched bridge at Saint-Nazaire and passing through the coastal pine forest before driving onto the coastal flats and salt pans around Beauvoir-sur-Mer. Here we pick up the 2.5-mile tidal causeway to the Île de Noirmoutier and rattle across the cobbles. As it’s low tide, there are hundreds of cockle-pickers out on the mudflats with rakes and buckets, looking for dinner. The superb, beachside Huttopia-run eco-campsite on the east coast has a sink that must only be used for cleaning seafood. That’s how seriously they take it.

The road south from Noirmoutier (D38, over the new bridge and on to Sables d’Olonne) passes through the Marais Poitevin, a huge wetland they call the Green Venice. It lies to the west of Niort and can be visited by kayak, boat or bike. We cycle down leafy dykes between the waterways and spot coypu in the ditches and canals of this important and beautiful wetland area.

Our final stop is the Île de Ré, the swankiest of all the islands. It’s low-rise, with tiny, cramped villages sitting in between the pines and the salt flats. Camped among the trees, we wake to the smell of pine warmed by the sun. We explore by bike, following cycle routes through the forest to marinas, swimming spots and restaurants. A late and leisurely lunch of moules frites in Saint Martin-de-Ré gives us time to watch the yachties live it up on their cruisers in the harbour. We are here just in time: as night falls, people gather for the 14 July celebrations. The son et lumière firework show lights up the sky in a noisy, joyful celebration of liberty, equality and fraternity.

Where to stay

Camping le Moulin des Oies, Brittany: close to Morbihan, this is a real gem, with a seawater pool and a pizza restaurant (from €14 for a pitch for two, including van).

Camping Huttopia Noirmoutier, Vendée: it’s popular, but book ahead and grab a pitch adjacent to the famous cockle-picking beach (from €60 a pitch, two-night minimum).

Get there

Brittany Ferries runs from Portsmouth to Saint Malo (11 hours overnight). It’s a drive of less than three hours to Quiberon (138 miles).

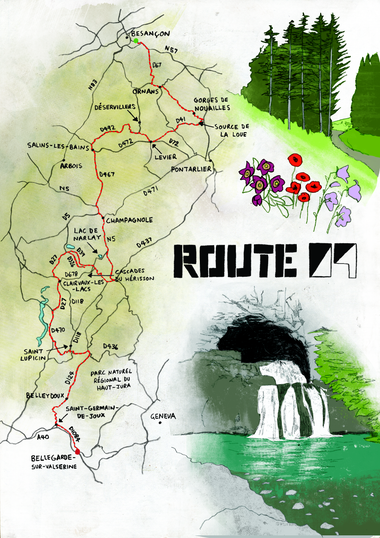

The Jura

Start Besançon

End Bellegarde-sur-Valserine

Distance 155 miles

Allow 4 or 5 days

We begin our journey in Besançon with a few lengths of the Olympic-sized pool next to Camping de Besançon, a 4.5-mile cycle from the medieval city along the river. Driving away, heading roughly south on the N57, we turn towards Ornans and pass meadows and tiny villages, before entering the deep and mesmerising gorges de Nouailles and beyond to find the source of the River Loue, a raging torrent that gushes from a limestone cove. The D41 leads us through more stunning mountain scenery to the source of the River Lison, where water floods out of a limestone cliff from within a cave, flowing over a waterfall into a deep plunge pool. The water is icy cool and makes my skin sing. I don’t stay in for long.

We continue south through the salt-making town of Salins-les-Bains and then the “gateway to the Jura”, Champagnole, before overnighting at Lac de Narlay, a popular lakeside campsite. In the morning we rise early and skinny dip, the lake gently steaming to greet us in the morning sun.

Bellegarde-sur-Valserine Photograph: David Broadbent

A short drive brings us to the Cascades du Hérisson, a stunning 2.5-mile stretch of river in a deep, forested gorge with falls along its length. We find a deep, undercut pool and swim, rising behind the falls to clamber onto a ledge and peer out through a curtain of shimmering water.

Our route takes us on to Clairvaux-les-Lacs and another stunning campsite on the water, surrounded by mountains. From here we head towards Saint-Lupicin on the D118, a perfect winding mountain road, through forests of hazel, oak, beech, viburnums and larch, past meadows filled with wild sage, delphinium, betony, scabious, meadowsweet, campanula, harebells and yellow rattle. My partner Lizzy, a botanist and gardener, insists we stop to take pictures every few metres (it seems). I don’t mind – the Jura is surprising me constantly.

We drive onto Saint Lupicin, Saint-Claude and towards Belleydoux over the Col de Croix de la Serra (1,050m), a road that’s partly forested, with a dotting of houses and farms, beautiful meadows with clanging cow bells and meadowsweet lining the verges.

From Belleydoux we follow a forested river gorge to Saint-Germain-de-Joux, then on to the D1084, the main road between Nantua and Bellegarde-sur-Valserine, on the final stretch before we meet the young Rhône. Another slow road adventure is complete.

Where to stay

Camping de Besançon: a fantastic campsite just outside Besançon, along the river. A fabulous cycle into the medieval city. Brilliant open-air pool next door (€18.50 per night for two, includes access to pool).

Camping du Lac de Narlay: direct access to Lac de Narlay. Electric pitches are terraced, the rest is a free-for-all (€18 per night with electric).

Camping le Grand Lac, Clairvaux-les-Lacs: just moments from the lake beach (€31 per night for two).

Get there

Take the ferry from Dover or Eurotunnel to Calais, then drive to Besançon in around six hours (370 miles).

Martin Dorey’s Take the Slow Road: France – Inspirational Journeys Round France by Camper Van and Motorhome is published by Bloomsbury (£20). The Take the Slow Road series includes the new Scotland, Ireland and England and Wales and is out now