One evening during Melbourne design week, I was drinking warm prosecco in a dimly lit third-floor office that overlooked Russell Street in the city’s centre. A friend had asked me to accompany her to the exhibition opening being held there. Of course, the office belonged to an architecture firm.

The crowd was stylish in a typically Melbourne way. There were black-rimmed glasses, workman’s jackets and designer sneakers in every corner. But as I scanned the photographers and brand directors in attendance, I realised at least half the room was wearing the floating, sculptural silhouettes of Issey Miyake, easily distinguishable by the tiny, perfect pleats that somehow give form and also take it away.

Miyake died this week at the age of 84, leaving behind a formidable legacy. He founded his studio in the early 1970s and was one of the first Japanese designers to present collections in Paris. He began to experiment with pleating in the late 1980s, finally patenting the heat-pressing technique that created permanent pleats in polyester in 1993.

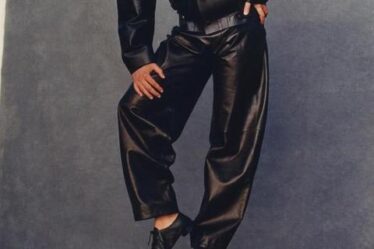

This formed the basis of Pleats Please, the line of clothing that is arguably his most recognisable, with its loosely tapered pants, tops with the shoulder and sleeve rounded into one, and rippling calf-length shift dresses. This look, often accessorised with his signature Bao Bao bag, has become synonymous with Melbourne style (to the point of occasional parody).

That each shape can be worn with something sporty such as a sneaker, or something delicate like a strappy sandal, is a credit to the joy, universality and freedom Miyake determinedly imbued in his garments.

Robyn Healy, a professor of fashion design at RMIT University, says this fluidity is why his designs have been part of Melbourne’s fashion culture since the early 1980s. “Dressing in clothes that were not based on European traditions of making, gender or season alignment appealed to Melburnians,” she says. In contrast to the body consciousness one might typically associate with Australian style, residents of the country’s self-proclaimed cultural capital “were attracted to clothing that draped, wrapped or hung around the body”.

Lucinia Pinto carried Issey Miyake at several boutiques she owned across the city from the 1970s to the early 2000s. She is firm in her belief that his designs influenced the way Melburnians dress. “The clothing appealed to people who appreciated art … So, it became a mainstay of Melbourne architects, for instance, who loved the detailed construction and the fit.”

In 1997, she collaborated with Miyake to open Australia’s first and only Issey Miyake store in South Yarra. She describes it as a vaulted space, made up of lime-green wall panels and a white vinyl floor. “It was the perfect backdrop for his work which was a mixture of tailored and pleated items, many of them Melbourne-black, but others in electrifying colours.”

Five years later Pinto closed all of her boutiques, making Miyake harder for Melbourne’s creative class to find – at least until the advent of online shopping.

Now, two decades later, the soft shapes and amorphous hemlines are available at Shifting Worlds on Elizabeth Street. Maya Webb, the store’s owner, attests to the longevity of the clothes – some of her clients still have Miyake pieces they bought from Pinto in the 1990s. “Miyake designs seem to be held on to in a way that other brands aren’t,” she says.

She believes Melburnians love Miyake because “it fits so well into a ‘casual luxury’ category” that suits a city defined by its culture, not its beaches.

Pinto describes Miyake’s work as “a joyful, sculptural ‘dance’ of fabric to partner the human form”. Fashion that sits in the nexus between construction and art has had a lasting impact on local designers. From the ruching and necklines of Permanent Vacation to the draping and form of Alpha60, Miyake’s influence is evident.

Alpha60’s creative director, Georgie Cleary, says: “He managed to combine art, fashion and innovation so seamlessly in his designs, and this is something we continually strive for.”