LOS ANGELES — Rhuigi Villaseñor wasn’t supposed to be sitting in the perennially leafy courtyard of West Hollywood’s famed Chateau Marmont hotel on a recent Tuesday morning.

The founder of LA-based label Rhude now spends most of his time at the headquarters of luxury brand Bally (split between Caslano, Switzerland and Milan) as well as visiting friends and new cities across the continent to keep the ideas flowing. “I’m pretty much European,” the 31-year-old designer joked.

A last-minute trip west allowed him to sort out some Rhude business before heading back to Europe, where he is set to show his first collection for Bally during Milan Fashion Week on Sept. 24.

Villaseñor, who first gained notoriety as a collector and seller of vintage menswear before launching casual-luxury line Rhude in 2016, was named creative director of the Swiss luxury brand in January.

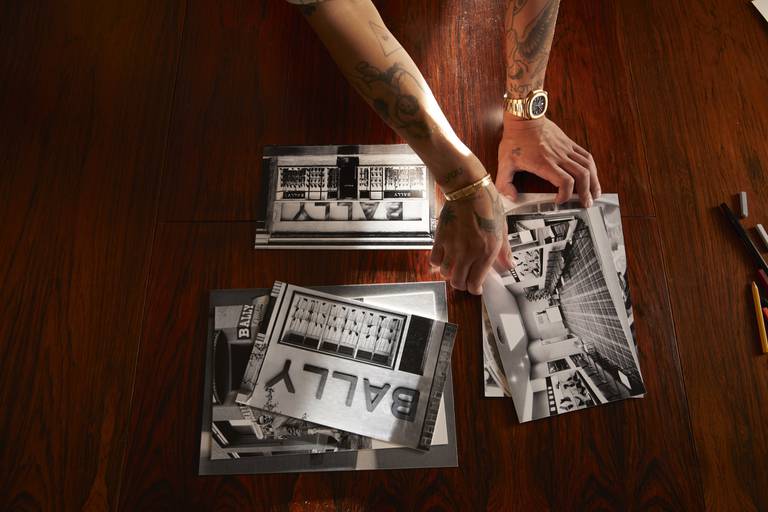

While he wouldn’t reveal any new product just yet, Villaseñor was eager to show off Bally’s re-engineered logo, which drew inspiration from the brand’s storefronts that were designed by architect Robert Mallet Stevens in the late 1920s. (The new identity, from the product tags to the advertising campaigns to new store furniture, will be rolled out over the next six months.)

The custom typeface is sans-serif (like nearly all luxury logos these days), but with beefed-up letters that have been stretched horizontally. The result, bold and unapologetic, was a passion project for Villaseñor, who grew up brand-obsessed.

Born in the Philippines, Villaseñor’s family moved to Los Angeles when he was 11. His teenage years were spent in Woodland Hills, a pretty little suburb in California’s San Fernando Valley known for its architecturally significant homes and above-average public schools. Even before moving to the US, he worshipped American companies like McDonald’s and Coca-Cola. Living in the picture-perfect Valley — in many ways the epicentre of American mainstream culture in the 1990s — gave him real-life experience.

“When I was in the Valley, I didn’t really know what was going on in the city,” he said. With Rhude, he set out to bridge the more common, dressed down style of the suburbs with the glitzier look that the city projected. “At the time I was thinking so micro. I just wanted to be impressive in L.A.”

Villaseñor now lives in the glitzier Hollywood Hills, in part thanks to the rip-roaring success of Rhude, which quickly became known for its typography-covered basketball shorts and rich motifs on graphic tees, worn by the likes of Kendrick Lamar and LeBron James. It has since expanded into a full line of casual wear for both men and women (Kendall Jenner and Saweetie are fans.) In the wealthier pockets of Los Angeles, you’ll often see Rhude mixed with popular luxury labels like Louis Vuitton, Fendi and Dior: it almost serves as a base layer for the logo-loving customers. (This year, the line is on track to generate more than $50 million in sales, according to a person familiar with the figures.)

Bally, too, has a history of serving conspicuous customers, albeit decades ago. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, the brand’s designer sneakers became popular with hip hop artists — immortalised in Slick Rick & Doug E. Fresh’s “La Di Da Di” video — influencing Black consumers and beyond well into the 1990s and long before other luxury brands pushed into the sneaker market. At the same time, the brand’s modest blake-stitched Scribe oxfords dominated the men’s dress shoe sections of American department stores.

Gene Pressman, former co-CEO of Barneys New York (which was founded by his father) remembers the line’s rise in prominence.

“I never thought Bally was cool,” Pressman said. “Later on, I thought it was sort of slick.”

By the end of the 1990s, however, the company was in the red. The brand changed hands repeatedly, from Swiss technology firm Oerlikon-Bührle, to private equity firm TPG in 2000 — which turned it around in the early aughts by increasing distribution through both direct and multi-brand retail and bringing more production in-house. In 2008, TPG handed it off to JAB Holdings, a conglomerate owned by Germany’s billionaire Reimann family.

When JAB first acquired Bally, it was a part of its burgeoning luxury group Labelux, which aimed to compete with the likes of LVMH and Kering with a portfolio of brands that also included Jimmy Choo and Belstaff.

Under JAB’s ownership, Bally collaborated with the likes of Swizz Beatz and J.Cole to help re-establish its pop culture relevance. It also sought to raise awareness of its singular position as the only global leather-goods label to emerge from Switzerland —a country better known for its timepieces.

But luxury conglomerates have made it hard for smaller players to compete on a global stage, and within a few years JAB decided to give up on its luxury ambition, officially closing Labelux in 2014 and selling its interests in Jimmy Choo and Belstaff in 2017.

A year later, the group attempted to sell Bally to SMCP-owner Ruyi for about €600 million, only to see the deal fall through when the Chinese group couldn’t come up with the funding.

Last year, Bally executive Nicolas Girotto — who joined the business in 2015 and was promoted to CEO in 2019 — told BoF that there was no deadline for an exit.

But it’s unlikely JAB will remain in the fashion business long-term. In order to spark momentum, Girotto is relying on Villaseñor to develop a 360-degree wardrobe: office wear, casual wear, and everything in between. He’s also put him in charge of marketing, advertising and store design. Anything that touches the brand.

This wasn’t always the plan. “There was no recruitment process,” Girotto said. Originally, he brought Villaseñor to Switzerland to speak about collaborating on a multi-season capsule collection, but after further discussion, decided to offer him the all-encompassing creative director role. “What surprised me and interested me is his ability to to marry the codes of old luxury and streetwear — or what the kids are wearing right now,” he added.

But Villaseñor insists this isn’t another streetwear play. For one, women’s ready-to-wear will be a major focus. (Girotto said one of his goals is to “rebalance” the product lineup up between men and women — right now it’s 60-40, in favour of men’s — and that apparel is already growing. The goal is for ready-to-wear to make up 20-25 percent of revenue in the near term.)

To build the first collection, he sought out pieces from Bally’s mid-century archives to inspire what he calls a “sexy, elegant, sophisticated wardrobe,” noting that the collection is his first time designing proper women’s clothing, handbags and shoes.

“For me to reference an era of hip-hop for Bally would be so…preliminary,” he said. “It would be like the first layer of design. Hip-hop itself is deeper than that. It’s jazz, it’s rock-n-roll. It’s a reference to so many other things.”

It’s Villaseñor’s obsession with popular culture more broadly — and where it’s headed — that landed him the Bally job in the first place. For instance, he and Girotto bonded over a shared interest in cars and watches. (Villaseñor is a Formula 1 follower, now one of the fastest-growing sports in the US, and has collaborated with McLaren.)

He also has an instinct for what people are willing to pay. When he launched Rhude, he priced his garments higher than many of his competitors to show that he was confident in the value of his wares. (Screen-printed t-shirts start at around $225, while the signature logo short is $495.) It worked.

“Being a vintage collector kid was a real education,” he said, recalling a time when he put a well-known label on a random piece of clothing, and sold it to a friend for an “insane” price. (He eventually told the friend, and said they still laugh about it.) “That taught me branding and marketing, and when I started my brand I believed in it the way I believed in that label when I put it on something else.”

With Bally, he has to once again convince consumers — and an entire industry — that his wares are worth the attention and money. One thing that will help is that Bally is already a well-known brand with global distribution, with 160 directly owned stores and 160 stores operated by franchise partners. In 2021, annual sales were near pre-pandemic levels of CHF 350 million ($355 million), according to the company. Girotto has already gone to work recalibrating that store fleet — for example, closing a store on the Upper East Side and opening one in the Meatpacking District — in the hopes of attracting a younger customer. He said that while the network in Asia is solid, he’s eager to increase the brand’s presence in the US — Villaseñor’s key market — and refresh its image in Europe.

“As long as the brand is willing to invest, there’s an opportunity to increase relevance because that infrastructure is in place,” said Nickelson Wooster, a creative consultant and longtime menswear buyer. “What Rhuigi in turn can do is inject life into a brand that has a huge history but is kind of blank. It’s open to interpretation.”