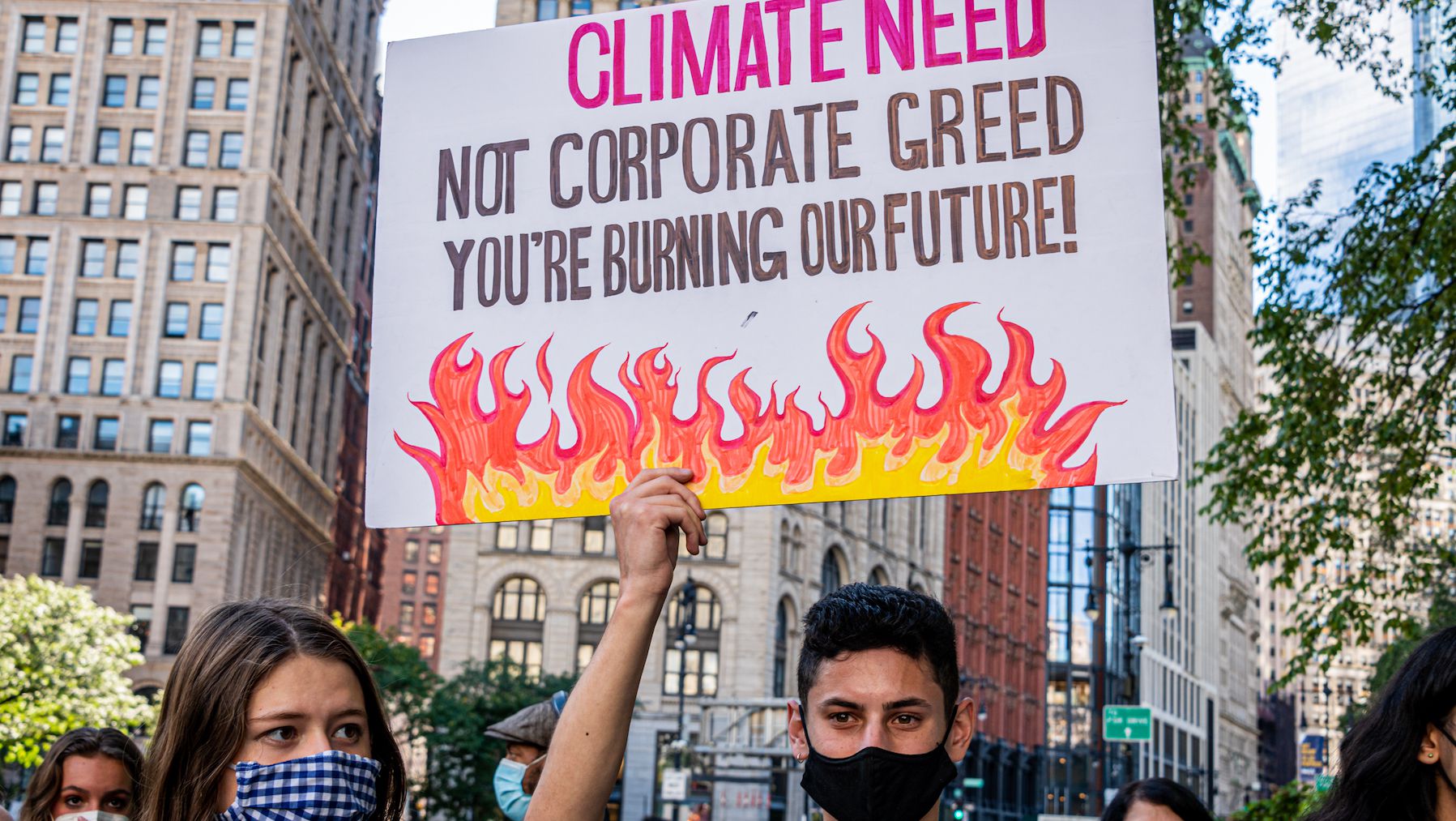

This week, as the fashion flock gathered for fashion weeks in London and Milan, global leaders and climate experts descended on New York for the UN General Assembly and Climate Week, a major summit focused on action to curb global warming.

Though this summer’s weather extremes left little doubt that action on global warming is more pressing than ever, equally apparent were political and financial pressures that are jeopardising action even as the world cruises past critical tipping points.

Usually, global climate summits are a major marketing moment for big corporations and investors to trumpet their commitment to environmental action — fashion included — but announcements this week were decidedly light.

Instead, political speeches focused more on the war in Ukraine and associated energy crisis than climate. A spicy episode in which Trump-appointed World Bank chief David Malpass was accused of (and eventually denied) being a climate denier resurfaced criticism that the institution is not doing enough to tackle climate change and hinted at partisan divisions that are fuelling a backlash against ethical investing.

And reports emerged that a number of banks have threatened to pull out of a major green alliance over legal risks associated with hard targets to stop investing in coal, oil and gas.

It’s an illustration of the limits of voluntary commitments and it applies equally to the fashion industry as it does to finance.

Ultimately, it’s a question of business: big corporations have yet to find a way to make good on climate commitments and keep making more money.

It’s not a new tension, but we’re reaching the pointy end of it.

Global emissions need to peak by 2025 and decline rapidly after that to avoid the worst effects of climate change, according to the UN climate science agency. Even then, global warming could still trigger some climate “tipping points,” a study published last week found.

And yet progress towards fashion’s sustainability goals is glacial: the industry’s frontrunners, from Puma to Gucci-owner Kering, are making only incremental advances and that masks much broader inaction, The BoF Sustainability Index found.

Many companies still have climate goals that are set relative to sales, meaning they can keep growing emissions alongside bottom lines and still hit targets. Even Patagonia, which made waves last week by restructuring to funnel all its profits into climate action, grapples with the tension between maintaining profitable growth and managing environmental impact.

Changing this dynamic, particularly at the pace needed to seriously tackle the climate crisis, is unlikely if left to businesses alone. Regulation can help, bringing accountability to commitments and incentivising and subsidising costly changes.

Consumer demand has also proved a healthy catalyst for action — especially as advertising watchdogs begin to crack down on brands seeking to capitalise on this interest without taking real action.

On the flipside, inflation and economic headwinds remain immediate and distracting pressures ahead of the UN’s next major climate conference in Egypt in November.