KEY INSIGHTS

- Proenza Schouler was a darling of American fashion, fuelled by millions of dollars in investment and the early success of its PS1 bag.

- By 2018, mismanagement, mounting expenses and wider market shifts left the company in distress.

- Chief executive Kay Hong says a “profitable, sizeable business” is still within reach.

There were times over the past 20 years when Proenza Schouler’s Jack McCollough and Lazaro Hernandez — the designers behind what was once the most promising brand in American fashion — weren’t sure if their business would survive. But somehow, they always made payroll, always shipped the collection, always staged their runway shows.

Fashion can be a business of smoke and mirrors, especially for upstart labels, and Proenza Schouler never let the cracks show. Their story was too much of a fairy tale.

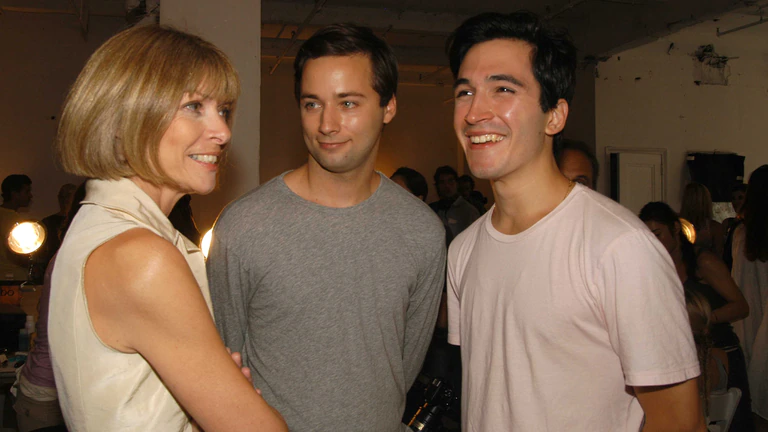

From the beginning, McCollough and Hernandez were American fashion’s chosen ones. Chosen by Julie Gilhart, then the influential fashion director of Barneys New York, when she bought their Parsons senior thesis collection in 2002. Chosen by powerful American Vogue editor-in-chief Anna Wintour, who recognised their winning combination of talent and good looks, and helped them stage their first proper show at the National Arts Club in 2003. Chosen by top critics who saw that their stylistic point of view — uptown tweeds and bustiers, rendered in comic-book colours and de-bulked for thin, young women who smoked in bars downtown — brought something new to the fashion conversation.

“I have met so many young designers and I’m always asking them: What exactly is it that you want to say?” Wintour said in a recent email exchange. “And here was Jack and Lazaro who, from the very beginning, had found their voice.”

In 2004, Proenza Schouler won the first-ever CFDA/Vogue Fashion Fund, set up in the aftermath of the September 11th attacks.

“It’s important to remember what 2002, when Jack and Lazaro graduated, was like for young designers in this country because the reality was that we hardly had any — and those we did have were, just like their more established counterparts, suffering hugely from the impact of 9/11,” she said.

What came next in many ways followed fashion’s playbook for building winning designer brands at the turn of the century: industry endorsement begets interest from retailers, which begets investment, which begets a hit handbag, which begets more investment and awards and, ultimately, the attention of a powerful fashion group.

At the time, French giant LVMH had a history of buying up the labels of the young designers it installed at its heritage houses. If you were a rising talent in the early 2000s, the goal was to get the kind of deal that Marc Jacobs scored when he joined Louis Vuitton in 1997, or John Galliano had at Dior.

But the playbook didn’t always work, even for those with plenty of advantages.

By the summer of 2018, 15 years after launch, Proenza Schouler was at a low. Facing slowing sales and mounting costs, its investor, the private equity firm Castanea Partners, was looking for an exit that would avoid the public embarrassment of bankruptcy. (Michael Banu, then a principal at Castanea, did not respond to a request for comment.)

Castanea, which first took a stake in the company in 2015, had injected around $40 million into the business alongside a group of independent investors including Theory founder Andrew Rosen and John Howard — also the backer of brands such as Rag & Bone and Skims. They had collectively added another $20 million to the pot, bringing the total sum poured into Proenza Schouler to about $60 million, according to multiple sources familiar with the numbers. (Hernandez and McCollough declined to comment on financial figures.)

When Castanea first invested in Proenza, the brand was targeting $75 million a year in sales, according to a source familiar with the firm’s thinking.

Proenza Schouler’s first big business win was the launch of its PS1 bag. Introduced in 2008 on the back of an investment, the schoolboy satchel — often rendered in a matte, worn-in leather — became a foundational piece in the wardrobes of thousands of women. For several years following the launch, the bag accounted for 80 percent of handbag sales, and made up the majority of the company’s overall revenue.

A decade later, though, the PS1, while still a top seller, had fallen out of fashion, and the designers had yet to have another blockbuster product or a stable of items that sold reliably year after year.

Proenza made attempts to elevate its brand by showing during Couture Week in Paris, and expanded the product architecture by launching new categories, like swimwear and casualwear, as well as a fragrance. The company also expanded abroad, entering a deal with Singaporean boutique-turned-brand-manager Club 21 to open four stores in Asia.

In a shifting market, however, it wasn’t enough. Independent brands — even those with significant backing — were boxed out by luxury’s biggest players, whose heft gave them a major edge in distribution and marketing, where they enjoy greater leverage with multi-brand retailers, mall owners, real estate developers, magazines, influencers and other key players in the fashion ecosystem. In 2019, LVMH, Kering, Richemont, Hermès and Chanel controlled more than 40 percent of the market, according to estimates.

“We feel like we can stand up to any of those [big brands] on a design level, in our design ability,” Hernandez said. “We cannot compete in the marketing of the product … we can’t outspend these people.”

Another challenge: Hernandez and McCollough had never found the right executive to manage the business as it grew in size and stature. They started the company with their college friend-turned-CEO Shirley Cook, but when Castanea entered the picture, Cook was replaced, at first by one of the firm’s operating partners, the retailer Ron Frasch, and then by Judd Crane, a former Lane Crawford and Selfridges executive.

While the designers and their ever-growing board of directors agreed they needed new leadership to take the brand to the next level, the partnership with Crane never flourished. Retail expansion in New York, first a store in Soho, then one on Madison Avenue, stalled, with the uptown location closing soon after its opening. An attempt to launch a lower-priced, streetwear-inflected line, PSWL, was at odds with the main collection, and fell flat with customers. With the label unable to sustain or replicate the success of the PS1, the board became frustrated with the designers’ focus on the increasingly costly runway collection at the expense of commercial product.

“The commercial collection was a watered down version of the show,” McCollough said. “There was a big disconnect with what was being sold and what was being shown.”

As costs mounted, so did tensions between the board and the designers, none of whom wanted to face the public embarrassment of a failed venture.

“The more investors we took on, the bigger the board got, and we had this huge board, with all these heavy hitters, and everyone had an opinion,” Hernandez said. “Our voice was totally lost in that… we got lost in a sea of advice.” It was, as Hernandez put it, “a shit show.”

In the end, Mudrick Capital, a hedge fund, took an undisclosed stake in the business for $12.5 million in November 2018, according to a US Securities and Exchange Commission filing. Castanea — which isn’t likely to raise another fund, according to reports — and the group of independent contributors, led by Rosen, agreed to exit without a return. Hernandez and McCollough once again owned a controlling stake in the business.

“We were happy to walk away,” Rosen said. “We respected them and their talent, and wanted to give them another chance.”

A Turnaround in Progress

Mudrick was an unlikely partner for Proenza, a company that has never surpassed $70 million in annual sales, according to sources familiar with the business. The hedge fund’s success was primarily in the energy market — although it made headlines in 2021 for shorting AMC, the struggling movie theatre giant, and, more recently, for investing in Vertical Aerospace, a British flying taxi start-up. What Mudrick had, however, was a personal connection — managing director David Kirsch’s wife, Dani Stahl, a longtime fashion editor at Nylon magazine, revered the label.

Kirsch also had an idea for a chief executive who he believed would be a good match for McCollough and Hernandez. Enter Kay Hong, a “faux retired” turnaround expert credited with reforming plus-sized fast fashion firm Torrid and gifting company Harry & David’s.

Hong, 48, had no experience in luxury. She was, however, a Proenza Schouler customer, and had specific ideas about how to crystallise what the brand stood for.

“Inconsistency made it difficult to build a business.”

“My observation was that there was zig-zagging; an inconsistency,” she said. “Even as an outsider to this industry, I knew that inconsistency made it difficult to build a business.”

Hernandez and McCollough met Hong that September, around the time they presented a collection made entirely of denim pieces. The show, while straightforward in its execution, was divisive among critics, and said a lot about what was happening behind the scenes. While their two previous collections were shown at Paris Couture, using ateliers and materials favoured by houses with far larger budgets, this line was rendered entirely in denim, reflecting the need for a reset, not only creatively, but also financially.

“They needed to grow up,” Rosen said.

Hong, who is based in Lake Tahoe, Calif., agreed to take the job, and they set out to remake the business: not in the vein of what their better-funded competitors in Europe were doing, not in the vein of what streetwear’s newly crowned kings were doing, but instead focusing on sportswear worn by professional women. The label had expanded into new product categories years earlier, selling everything from swimsuits to cashmere sweats, but the assortment needed better alignment: Proenza’s ready-to-wear collection didn’t always gel with its accessories and lower-priced merchandise.

“Back in the day, we used to make clothes that our friends who are editors and stylists wanted to shoot,” Hernandez said. “Now, we’re making clothes they want to wear.”

Hong went to work streamlining Proenza’s operations and executive team. By 2020, the label was positioned for growth once again. Then the pandemic hit.

Thanks to a logistics overhaul executed a year earlier, Proenza Schouler’s spring collection was by March already in stores and paid for. By luck, their collaboration with Birkenstock — for which they topstitched the German sandal-makers’ popular Arizona and Milano styles, glazing them in what have become signature colours like cobalt blue and burgundy — went on sale that same month, just in time for the leisurewear explosion.

In the end, sales were down 12 percent in 2020, a tough year for the sector. But in 2021, they jumped almost 40 percent over the previous year (20 percent up from 2019).

Hong declined to share current sales figures, but said that, while the PS1 remains the brand’s best-selling bag, revenue is more evenly distributed among categories than in the past, with 60 percent of sales coming from clothes and 40 percent from accessories and shoes.

The secondary line, rebranded Proenza Schouler White Label, now makes up 30 percent of revenue, while direct retail, including one physical store and e-commerce, accounts for 20 percent of business, up a few percentage points from before the pandemic. These days, the brand also has a significant global presence, with 40 percent of sales coming from outside the US, even though its deal with Club 21 is no longer active. (Hong said new stores, both in the US and abroad, are part of the longer-term growth plan.)

“The big difference in our business then versus now is that the only true commercial success we had was the PS1 bag,” Hernandez said. “All of our eggs were in that basket.”

What Hong seems to have brought is the kind of business partnership many designers seek, but never find — and something Hernandez and McCollough said they haven’t had since their early days with Cook.

“What is happening here is because of all three of us,” Hong said. “We all have our own roles, but we’re not siloed out. We’re in constant communication on direction and strategy.”

Hernandez and McCollough seem more at ease with the realities of running a business — and relieved to have Hong in place. “She helps us navigate our ideas,” Hernandez said.

“We’re blurring a line on what’s a showpiece, what’s a commercial piece,” McCollough added. “You can’t tell what was shown, what was not shown. That’s a part of the puzzle that we love now.”

Their last two shows have reflected that change: no longer does it feel like that they are chasing the essence of the season, but honing their offering with a focus on slick, sculptural dresses and separates that are distinguished by fringe, swirling prints and amoeba-like cut-outs. They’re making clothes that women like Hong, who spend real money on what they wear to work, or dinner or a vacation, buy into because they’re sexy but also easy-to-wear and mature.

The Road to Rebirth

The road to that realisation, however, has been long and arduous. Everything happened so fast after Gilhart bought the collection, with Wintour positioning them as poster boys for a generation of American fashion.

“It was an attitude, the way they approach design,” said Samira Nasr, a former Vogue editor and current editor-in-chief of Harper’s Bazaar, who styled their first runway show in 2003. “André [Leon Talley] got behind them, Anna. There was an optimism to what they were doing.”

Not only were they a talented and photogenic couple, but they had cool, rich and famous friends like Jen Brill, Vanessa Traina and Mary-Kate and Ashley Olsen, who wore their looks to galas, on magazine covers and in paparazzi shots.

“We became close very quickly,” said Sara Moonves, now editor-in-chief of W, who met the designers when she moved to Manhattan to attend New York University. “They were already a thing when I got here.”

While they were sometimes criticised for their privileges — for instance, Michael Kors, with whom Hernandez interned, donated the fabric they used for their Parsons collection, according to an early New York Times report — those who followed fashion accepted them as the next generation’s Marc Jacobs or Isaac Mizrahi: real stars.

The brand’s high-profile associations resulted in mentions in every magazine, from US Weekly to French Vogue, and in 2006, Hernandez and McCollough launched a collaboration with big-box retailer Target. The capsule first went on sale at Carol Lim and Humberto Leon’s Opening Ceremony — at the time the most influential retailer of young fashion in New York — garnering a queue out the door before hyped retail drops were common.

Just months later, five years after Barneys bought Proenza’s first collection, Valentino Fashion Group (VFG), which included Valentino and Hugo Boss, paid $3.7 million for a 45 percent stake in the business, according to a report in Women’s Wear Daily. (Adding complexity, London-based private equity firm Permira had recently invested in VFG.)

There was talk of McCollough and Hernandez taking over for Valentino Garavani when he retired, but the deal was ultimately a straightforward investment. The duo said they never really considered not accepting the financing. “We needed the money to keep going,” Hernandez said.

“The pressure in the beginning was challenging,” McCollough said. “We never worked anywhere else, and we were still figuring out who we were as designers. It was difficult in some ways.”

For a while, the approach paid off. In 2008, shortly after receiving the VFG investment, they released the PS1. At just over $1,000, it was affordable enough for affluent 20-somethings to purchase, and sophisticated enough for older, wealthier customers to buy. The success of the bag — conceived in collaboration with handbag designer Darren Spaziani, now artistic director of leather goods at Louis Vuitton — accelerated sales.

The designers and Cook, their CEO at the time, were eager to have the sort of support a strategic group could offer compared to Permira, a private equity firm that had been interested in Valentino and Hugo Boss, huge companies that could be sold off or taken public for a lot of money, not a small investment like Proenza Schouler.

Suddenly, LVMH was seriously looking at Proenza Schouler, not only as an acquisition target but also to potentially hire Hernandez and McCollough to lead one of its heritage brands. The designers were keen on Dior after Galliano’s exit in 2011, according to sources, though they would only say that they were interested in designing for a major house, and had been approached by different houses over the years, but the timing was never right.

A deal with LVMH, which looked at the business twice, never materialised. (Some sources cited deal exhaustion on LVMH’s side; others said the terms were never attractive enough to Proenza’s investors.) The pressure to produce another hero product began to weigh on the label, especially after Spaziani exited for Louis Vuitton in 2013. “You can’t plan a hit bag,” Hernandez said.

The only choice, they believed, was to raise more money. A few years earlier, Rosen and his investor cohort had bought out Permira after the firm began looking for an exit. (Permira also sold Valentino to Qatar’s royal family in 2012 for about $730 million.) Castanea entered the picture in 2015 when the possibility of being scooped up by a major fashion group still felt realistic.

That same year, they struck a fragrance deal with L’Oréal, although the terms were never disclosed and the royalties from “Arizona,” inspired by the energy vortex of the Southwest, contribute a nominal amount each year to the bottom line.

But by 2015, the big luxury groups were shifting their strategies. They were increasingly looking for star marketers, not star designers, to lead their largest brands, and were less keen on snapping up smaller labels, which they struggled to scale.

“I’m not sure that recipe can really work,” Kering chief financial officer Jean-Marc Duplaix told BoF in 2020. In recent years, the LVMH rival has purged smaller labels like Christopher Kane from its portfolio. LVMH, too, has shed smaller brands, like Nicholas Kirkwood.

This left Castanea holding a stake in a well-known, but hard-to-grow, brand that would need even more capital to reach any sort of competitive scale.

Ultimately, Proenza’s fortunes unravelled for many of the same reasons so many of its peers are no longer in business: misallocation of funds, disagreements with investors, seismic shifts in the industry at large, and a fashion ecosystem that did a poor job of preparing young designers for the realities of entrepreneurship.

After all, Hernandez and McCollough were two 20-somethings, right out of art school, when they got going. Looking at the list of brands that competed for the 2003 CFDA/Vogue Fashion Fund, Proenza is the only label that remains relevant to the international fashion conversation.

“It was fun winning all the CFDA awards,” Hernandez said. (The brand also took the Womenswear Designer of the Year award three times: in 2007, 2011 and 2013.) “What evaded us was creating a real business.”

Gilhart, who still works with young designers today as a chief development officer for consulting firm and brand accelerator Tomorrow, looks back on how labels like Proenza Schouler were advised and wonders if there wasn’t a better way.

“It was fun winning all the CFDA awards. What evaded was creating a real business.”

“We had a fashion system, very directed by press and media, and there was this need for them to mature into a global brand when maybe they weren’t ready for that,” she said. “We put too much pressure on them to evolve too quickly.”

External pressure was only one factor, however. Most start-ups fail, and fashion just happens to be an industry where failure, when exposed, is often viewed as a shame rather than a lesson.

“Anna Wintour, the fashion system, gives someone a chance, and it’s the question of, can they rise to the level required to be successful on their own?” Rosen said. “[Hernandez and McCollough] weren’t really capable of going to the next level, business-wise. Is it bad that Anna or the fashion system gave them that opportunity? No — it’s sort of cruel that it turned out that way, but that’s the world.”

Hernandez and McCollough, who are now both 43, hold themselves accountable.

“It was a little toxic,” Hernandez said of the early years. “We had our first show, we had the cover of this, the cover of that. We were named one of the top 10 collections in the world. We had to constantly outdo ourselves. But ultimately, it was our fault.”

And yet, it isn’t over.

Despite the challenges, Hernandez and McCollough have managed, time and again, to keep going and finding new funding sources, most recently during the pandemic, after raising another $4 million in 2019 and another $2 million in 2020, all from Mudrick, according to SEC filings.

Why do they keep getting chances? Part of it has to do with having the right friends and the right personalities, but also raw talent and sheer perseverance.

“There’s this thing that things came easy because they were good looking, and young and whatever. But it’s not a fluke.”

“They’re very disciplined,” Nasr said. “There’s this thing that things came easy because they were good looking, and young and whatever. But it’s not a fluke. It came with a lot of thought, care and hard work.”

Can Proenza turn things around? Hong said that, in 2021, the company will finally break even after years of losses and is on track to be profitable in 2022. The focus is on using their profits — not more investment — to fuel growth. (Over the years, they have briefly crossed into profitability, only to slip back into the red.)

“What’s crucial is just that slow build, not jumping into everything immediately and overspending and then being in a position of weakness and needing to fundraise and losing control of the company,” McCollough said. “The beauty of today’s world is that it’s very different from when we started this. Things are just so much more fluid. There’s not this kind of pre-described notion of how you’re meant to do things and the path you’re meant to follow. Back when we started, we were expected to have shows. We were expected to put up pre-collections, have a bag line, accessories, advertise: all sorts of things that sometimes I wish we didn’t jump into as quickly.”

Years ago, when they were in the midst of the “shit show,” Hernandez said that becoming a billion-dollar brand — one that could compete on a global scale with much older, more established names — was no longer a priority. Hong, however, doesn’t think it’s out of the question.

“I’m not going to put a number on it, but I do believe this can be a profitable, sizeable business,” she said, noting that there is a big opportunity in wholesale in particular to increase footprint and presence as more marquee brands take their businesses completely direct to consumers. (While the company declined to disclose any sales figures, market sources estimate that annual revenue currently sits between $30 and $40 million.)

Retailers have responded warmly to the reset. At Bergdorf Goodman, the brand’s shoe and bag businesses — both the main line and White Label — experienced double-digit sales growth in 2021. “We’ve seen both the loyal and new customer base growing,” said Yumi Shin, the Neiman Marcus-owned retailer’s chief merchant, noting that, like many brands, its knitwear “took off” during the pandemic. “We’ve sold a lot of dresses in the past, and now it’s really balanced across all categories.”

Regardless of whether Proenza is on the right course, Mudrick will eventually want an exit. The firm has held positions in companies for as long as 12 years, but the day will come when it wants out. There is still the belief that a sale to a group that wants to manage the brand long term, and not simply juice and discard it, is a possibility.

“I was sitting at one of those really big fashion shows recently, the kind with money and people behind them, and I always think about what Proenza would do with those kinds of resources,” Moonves said. “They’ve managed to have this staying power.”

For their part, Hernandez and McCollough are optimistic. Perhaps that’s why, at the beginning of 2022, they wiped their Instagram account clean. The first fresh post was an image of a blinding-yellow egg shell, cracked ever so slightly, against a blinding-yellow backdrop, and their mothers’ maiden names — Proenza and Schouler — in white in the typeface Neuzeit S, floating in the foreground. The caption simply read, “Rebirth.”

“There was so much stuff, so many different vibes that don’t feel relevant anymore,” Hernandez said. “We’re releasing ourselves of baggage from the past.”