When the Queen died, I, like many, turned to social media. Instagram was flooded with tributes to her enduring sense of duty and grace. But the steady stream of imagery showcased something else, too: her remarkable sense of style.

There she was in coronation garb and blue-sashed state dinner gowns. Scroll down and it was all pastel-coloured suits complete with matchy-matchy millinery. Scroll again and she was a vision of country life in tartan skirts and wellies, surrounded by her beloved corgis, or atop a horse in a tweed jacket and silk headscarf.

In the coming days, her sense of dress is sure to be appraised and re-appraised. But for some of fashion’s top designers, the Queen has long been a stylistic touchstone.

“The Queen is one of the most quirky people in the world,” Gucci designer Alessandro Michele told The New Yorker in 2016, on the eve of a show in London’s Westminster Abbey. Michele was one of the first major designers to pay tribute to the Queen yesterday, posting photographs of her, with her dogs and horses, in tweed coats, no-nonsense sweaters and signature headscarves, a styling device that has popped up repeatedly in Michele-era Gucci shows. Indeed, it’s easy to see parallels between the Queen’s off-duty style and Michele’s quirky revival of Gucci.

Fellow Italian Riccardo Tisci is also a fan of the Queen, citing her elegance as a key ingredient to the sense of Britishness he has worked to channel at Burberry. “She’s one of the most elegant, appropriate and polite figures in the world and part of what makes the UK such a fascinating place for me to be, because it’s the antithesis of that rebelliousness that’s also here,” Tisci told the Telegraph last year.

Indeed, admiration for the Queen’s dress sense is widespread among top designers. “She is one of the most elegant women in the world,” Miuccia Prada said back in 2000, during a royal visit to Rome. “She is never ridiculous; she is flawless,” echoed Karl Lagerfeld in 2014, commenting on her steadfast style.

Of course, enduring elegance isn’t always the most thrilling input for designers. And the constancy of the Queen’s image has pushed some in a more subversive direction. See Christopher Kane’s “Princess Margaret on Acid” spring 2011 collection where Norman Hartnell (designer of the Queen’s coronation gown) silhouettes clashed with Cyberdog neon. See also Erdem Moralıoğlu’s spring 2018 show, which was inspired by the 1958 meeting of Duke Ellington and a young Queen Elizabeth, who he reimagined as a party-going Lilibet dancing at the Cotton Club.

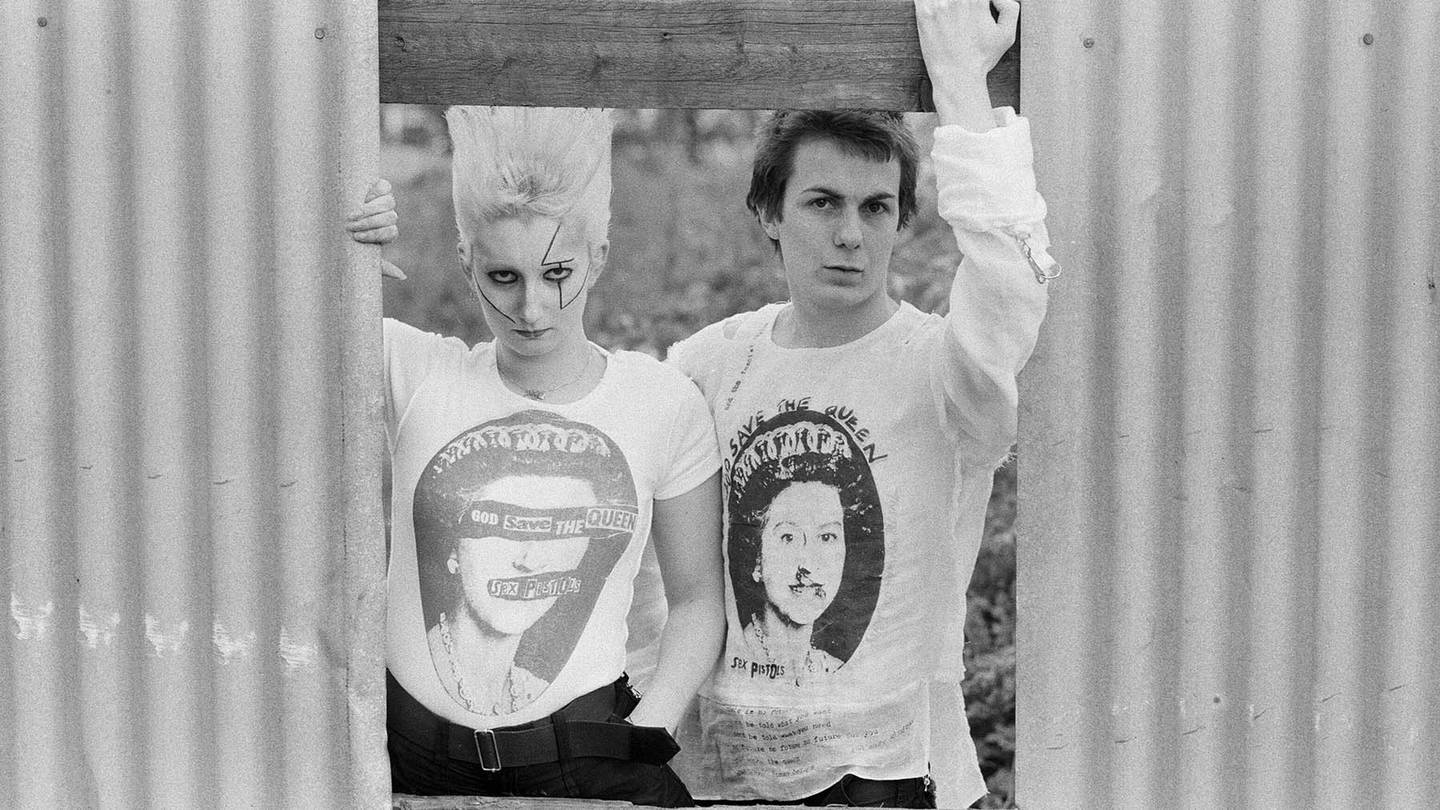

The original subverter of the Queen’s image, Vivienne Westwood, has done a 180-degree turn on the monarch. Yesterday, the designer paid a heartfelt tribute to the departed monarch. But back in 1977, she and then-partner Malcolm McLaren defaced Her Maj for their seminal “God Save the Queen” t-shirt.

Or was it a 360? Over the years, Westwood’s take on the Queen has oscillated between reverence and rebellion. In 1987, she showed Harris Tweed crowns on the runway. Four years later, she turned up knickerless to receive her OBE.

Perhaps the contradiction embedded in Westwood’s stance isn’t that surprising. The Queen was simultaneously an endearing human being and a figurehead for the British establishment, a side to her that other designers have also explored.

In 2008, Westwood and McLaren’s “God Save the Queen” t-shirt had another life as a distorted print that appeared in Alexander McQueen’s “The Girl Who Lived in the Tree” collection, which ruminated on Britain’s colonisation of India.

A generation later, the Queen remains influential with some young designers. In 2018, when she made her first (and only) appearance at a fashion show to present Richard Quinn with the inaugural Queen Elizabeth II Award for British Design, Quinn showed his trademark maximal florals on Balmoral-inspired ensembles of headscarves and padded jackets. Later he called the Queen’s style “daring and subversive.”

But not all of London’s young designers have been equally touched. They certainly haven’t been as eager as their predecessors with social media tributes. Surely, many will be busy dealing with the impact of the UK’s official mourning period on London Fashion Week. But it’s worth remembering that many of today’s talents, from Grace Wales Bonner to Supriya Lele, have postcolonial identities. Some of their work grapples overtly with the legacy of imperialism. They may naturally be less likely to see a British monarch as a style icon.

The world has changed. So has the United Kingdom. And it’s unlikely that any British royal will ever have the same influence on fashion again.