LONDON, United Kingdom — At London Fashion Week, the British class system is visible everywhere. The British Fashion Council’s homepage still proudly shows Queen Elizabeth II sitting front-row, shoulder-to-shoulder with Anna Wintour, at Richard Quinn’s Autumn/Winter 2018 show. At the other end of the spectrum, Samuel Ross-founded streetwear label A-Cold-Wall is presented as an ongoing love letter to Ross’s working-class upbringing.

Even the luxury brand most synonymous with the UK has its business tangled up in the country’s complex class system. Burberry once launched an entire rebranding strategy by downplaying its iconic check pattern after it became infamously mired in working-class “chav” culture. Interestingly, it now sells £550 trackpants and £650 trainers.

The constant collision between the elitist establishment and the irreverent anti-establishment is what many see as a strength of British fashion. In fact, some of the UK’s biggest moments in fashion history are testament to the trickle-up theory of creativity, drawing from punk, mods and rockers, rave culture and even football hooliganism.

“So much of the streetwear references we take for granted as being legit on the catwalks of Paris, Milan and New York today stem from the early work of brave, open-minded British designers, stylists and photographers in the ’80s and ’90s — and even the 2000s — who came from really, really humble working-class roots or even what people might call the underclass,” said Adonis Kentros, the London-based stylist consultant for Christopher Kane.

Queen Elizabeth II and Anna Wintour at Richard Quinn’s Autumn/Winter 2018 show | Source: Yui Mok/AFP/Getty

“Many of the young creatives who were from underprivileged backgrounds were the ones who wanted to reinterpret what was happening in their hometowns or on the [public housing] estate they grew up on,” Kentros continued. “They were critiquing the streets that they fled from or celebrating the community they felt secure in [and somehow] keeping it real. However they ended up using those class references, it was really personal.”

But some now argue that what drives this phenomenon is an unhealthy preoccupation with socioeconomic class and poor social mobility in the British fashion industry. As a more sophisticated awareness of cultural appropriation and tokenistic diversity comes to the fore, it makes sense to look at meaningful representation in terms of socioeconomic class and to debate the notion of “class appropriation.”

“Fashion has become a rich person’s job,” claimed Andrew Davis, a pastry chef-turned-stylist who blagged his way into an interview at Central Saint Martins and worked for The Face and Arena Homme Plus after graduating in 2000. “[It’s] such a shame, because CSM [used to be] such a mix of working-class kids and the children of lords and ladies who turned up to classes in a Merc.”

The trajectory of someone like Davis, who has styled for clients such as Calvin Klein, Nike and celebrities like Uma Thurman and Gwyneth Paltrow, appears to back up the idea that hardworking “grafters” can succeed despite the onerous class system which many see as stacked against them from birth.

But, two decades on from Davis’s first industry gig, is his experience the exception or the rule in fashion today?

Snobbery and the Scourge of Nepotism

“It’s definitely [still] a classist industry,” said Bianca Saunders, who started her own menswear line after graduating from The Royal College of Art in 2017.

“Growing up, I didn’t think so much about class and race until I started going into [fashion] education, where I was a minority, and noticing how different I was from everyone else in my class. I realised that I have to think about these things more and how much more it affects how successful you can be because of the social position you are in.”

It’s such an illness in British society.

Since entering the fashion industry, Saunders said she notices that those who have parents in the same line of work, or adjacent creative fields, “have been able to leverage the fact that they’ve always been around art, so they’ve learned a lot more. That’s why my research can come across as really broad; it feels like I’m learning things backwards.”

Saunders worked part-time to support herself through school. Although the experience helped her develop a strong work ethic, valuable personable skills and a network of contacts that have served her well in the industry, she said it is a double-edged sword.

“It has benefited me, but in the long term it’s an unhealthy way to live. I’ve always felt that I’ve had to work a bit harder to get things done. Not a bad thing per se but there’s a lot of self[-inflicted] pressure.”

Kitty Joseph is another designer who understands the challenges and importance of being resourceful in trying to break into the industry. “I had a supportive family, but they didn’t have very much money,” she said.

The Face covers | Source: Courtesy

Joseph, who grew up seeing the UK’s idiosyncratic brand of elitism through the eyes of her Australian mother, also found that classism and snobbery informed the choices she made starting out as a designer. “It’s such an illness in British society… [and in fashion] there are so many hidden languages and ways to behave. I consciously chose to go down the textiles route — I’ve always loved colours and patterns — because I thought it might be warmer and friendlier as a space than the fashion industry.”

While working for Zandra Rhodes on weekends, Joseph said she benefitted from a number of programmes and initiatives along the way, many of which are no longer available to budding designers.

Fortunately, she narrowly missed the sharp increase in tuition fees — and decrease in means-tested loans and grants — when she started university. “So many of my friends looking to study after the increase couldn’t take the risk,” she said.

Social Mobility Dilemma

As with any creative industry, a career in fashion is both hard work and financially precarious. But this leaves recruits from lower-income backgrounds at a distinct disadvantage.

Farrah Storr, who in addition to being editor-in-chief of Elle UK sits on the UK’s independent Social Mobility Commission, described the challenges of entering the fashion industry as “a web-like matrix of barriers,” starting with “poor career advice about what a job in the arts looks like” and extending to the nepotism of support networks, unpaid work placements and “a frightening lack of security” in the form of short-term contracts and freelance work. As a result, “only the very privileged or brave are prepared to face all of those challenges.”

The endurance of nepotism is evidenced in the reality of job postings: 85 percent of all roles are recruited by word-of-mouth rather than being openly advertised, according to data from Creative Access, a recruitment platform for people of colour and socioeconomically disadvantaged people looking for creative jobs. The social enterprise works with over 300 organisations including the BBC, Bauer Media Group and Christies.

Only the very privileged or brave are prepared to face all of those challenges.

According to a report on internships by social mobility charity Sutton Trust, 86 percent of work placements in the arts (including theatre, TV, film, fashion and music) did not pay the minimum wage, the highest rate of any sector, with working-class young people less likely to carry out internships in the creative industries than their counterparts from more affluent backgrounds.

“Social mobility in the UK is low and not improving,” said Dr Rebecca Montacute, research fellow at the Sutton Trust. “Where you are born and who your parents are play a considerable part in shaping the opportunities you have later in life.”

The problems with class-based representation in the industry can be traced back to the increasingly expensive institutions and courses that have turned out some of the biggest names in British fashion.

However, the biggest barrier that working-class talent face when trying to enter the fashion industry is not unique to Britain. The US, France and Italy — home to the three other fashion capitals of the world — have similarly poor rates of social mobility, with 2018 data from the OECD showing that, in all four countries, it can take at least five generations for the offspring of a low-income family to reach the average income.

What differentiates the UK from its country counterparts is that class is defined by a unique set of social and cultural factors — that ineffable convergence of money, family lineage, education, accent and even place of upbringing.

A Very Imperfect Haven

Criticising the fashion industry for its elitist shortcomings without acknowledging its progressive role in previous decades sounds one-sided to the generation of professionals older than Saunders or Joseph.

“Over the past 30 years, London’s fashion industry has had most of the problems that the industry had in other fashion capitals and I mean there have been a lot of serious problems,” said Kentros. “But it did embrace some people who were ostracised who could never make it in other industries, and that included a much more lenient attitude toward class.”

“I just think younger people in the industry today have much higher expectations — and rightly so — but the industry hasn’t been all bad either. Sometimes it was ahead of the curve and a safe haven and we shouldn’t forget that either.”

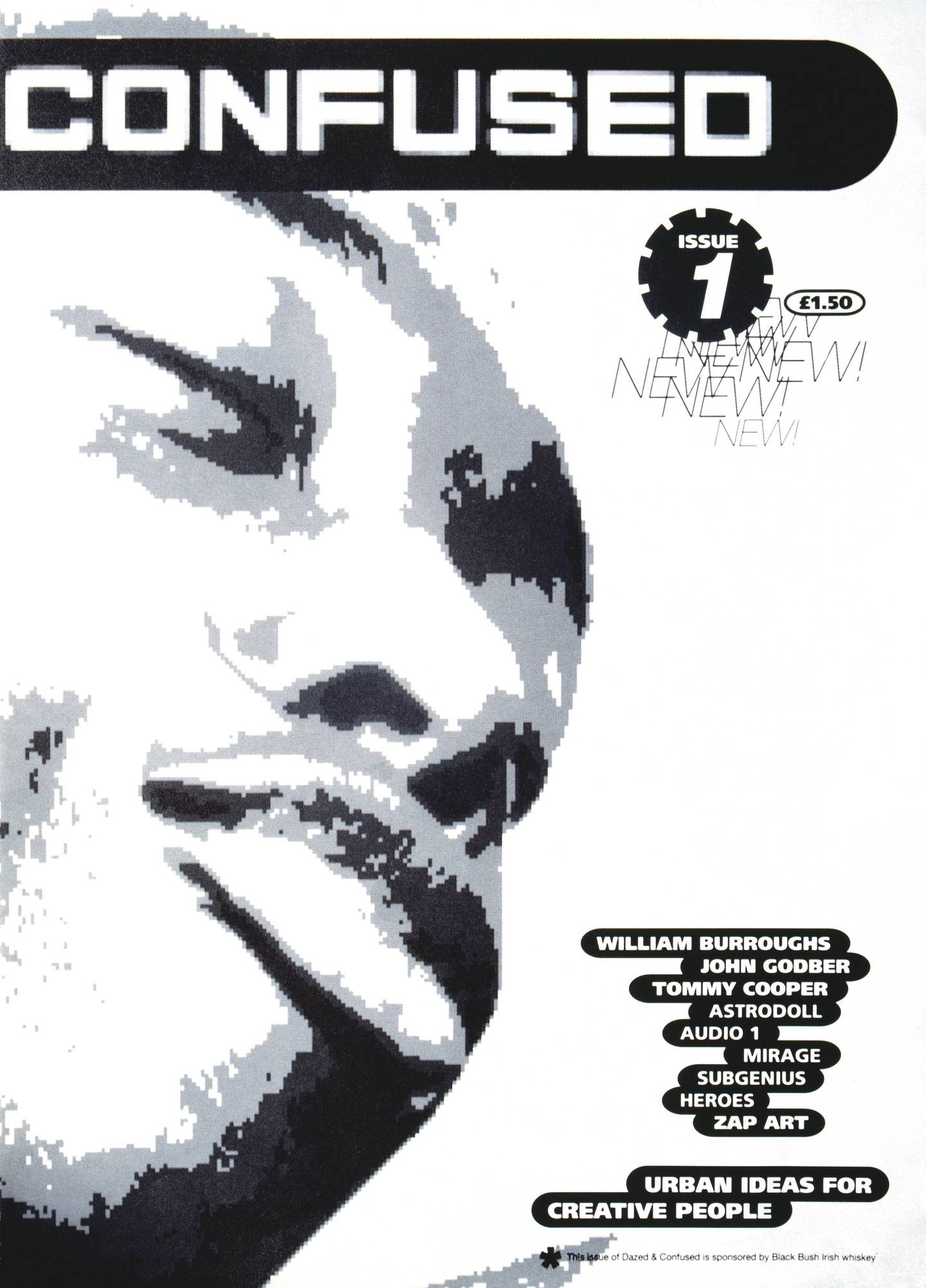

Dazed & Confused’s first issue, 1991 | Source: Courtesy

Kentros cited examples of industry leaders and fashion imagery from titles such as The Face, Sleazenation, i-D and Dazed, who in the ’90s and ’00s used class distinction as a creative schism filled with irony, humour, shock and awe. But he suggests that these earlier “style battles critiquing class” might be lost on a younger generation for whom advocacy and earnest activism are the medium of protest.

Jo-Ann Furniss, the Manchester-born fashion editor best known for her seven-year editorship of Arena Homme Plus, might agree. Arena was a magazine that distilled fashion subcultures of the day, with a creative output that was at once irreverent and intimate in the way it presented working-class aesthetics.

Furniss described the fashion industry of her youth as an “island of misfits” — a “way out” for women, LGBTQIA people and working-class people. “Now,” she said, “it has changed. [Fashion is] seen as a legitimate part of the entertainment industry in a way, whereas if you’re working class [and want to be upwardly mobile], it’s like, ‘why aren’t you doing law?’”

In the past (and some say today too), the British fashion industry was divided into two halves. “Back then, Tatler and Vogue and that whole set were running a very different fashion industry from the industry run by people at The Face, Dazed and i-D. But when these two worlds of class extremes collided, it could also produce amazing things. Just look at when Isabella Blow met Alexander McQueen,” Kentros recalled.

Indeed, the mid-to-late ‘00s saw the beginning of a convergence of the two sides of the British fashion industry. Previously situated firmly on the other end of the anti-establishment spectrum was the far splashier world of fashion PR firms and Condé Nast-owned titles — the culture of which inspired the award-winning BBC sitcom “Absolutely Fabulous,” first aired in 1992. The show’s protagonists, Christian Lacroix-obsessed PR Edina and her champagne-swilling fashion editor friend Patsy Stone, were caricatures plucked straight from the West End world of moneyed fashion who occasionally collaborated with the raw and raucous fashion creatives of the East End, many of whom were working-class.

But sometimes life imitates art, and when the upper classes dabble in the palette of the working class, the resulting artwork is often a pastiche.

Class Appropriation and Alienation

For Davis, this was epitomised in Vogue‘s July 2005 issue. Just one month after controversially doing a spread on “WAG” media personality and footballer Wayne Rooney’s now-wife Coleen McLoughlin, the publication featured Vicky Pollard, the fictional character from comedy sketch show “Little Britain” who had come to embody the media’s demonisation of “chav” culture with her hot-pink tracksuit, “Croydon facelift” ponytail and defiant back chat in the face of any figure of authority.

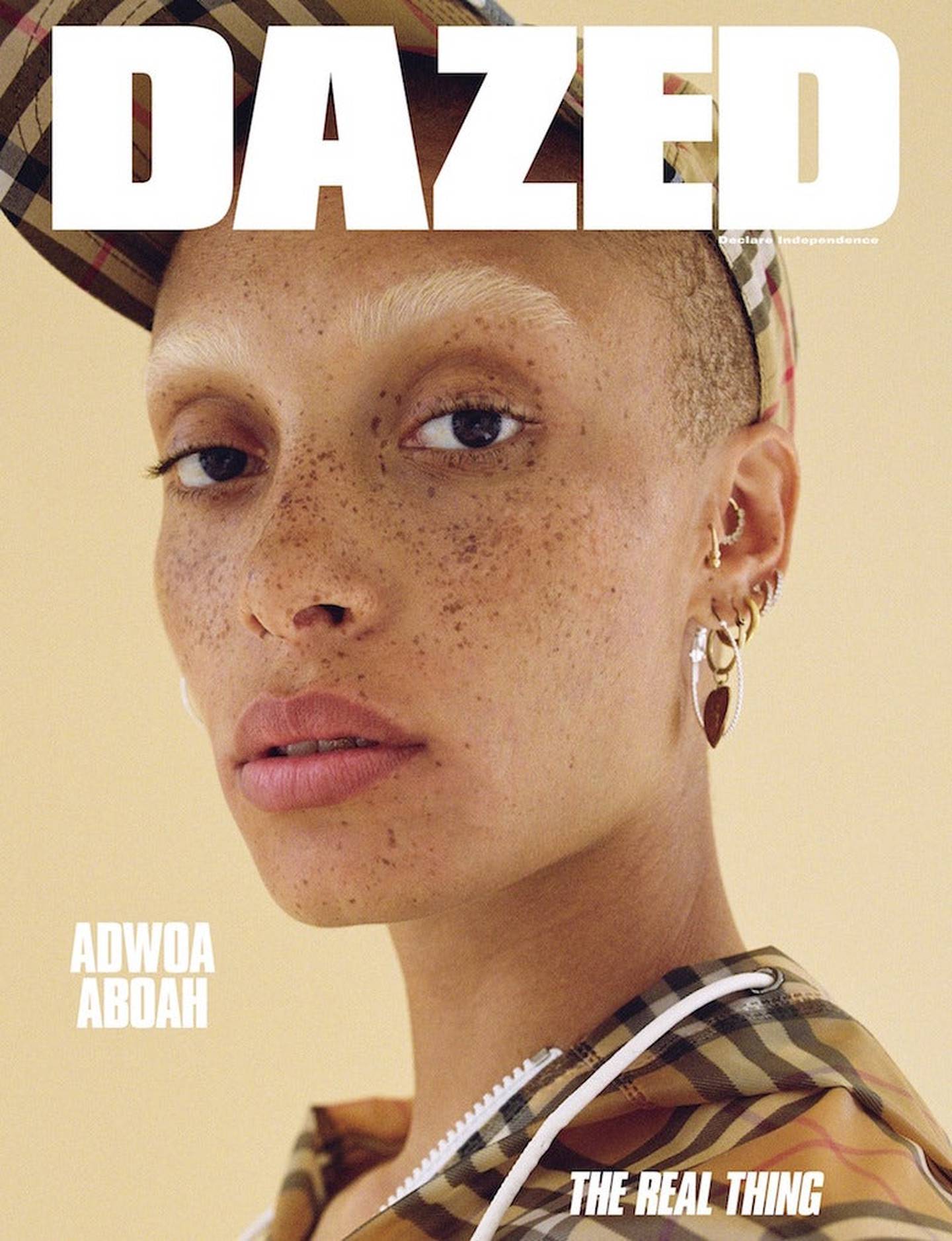

Dazed Autumn/Winter ’17 cover | Source: Courtesy

“It was almost like they were taking the piss,” said Davis. “When I started shooting for The Face, I was keen to shoot real people in their environment. If they were in a tracksuit, it’s because they wore a tracksuit.”

Attempting to embrace the very group that they are presenting — and often failing at it — is something that hasn’t gone away. So-called “class appropriation” (a take on cultural appropriation that involves superficially co-opting aspects of a lower socioeconomic class, rather than a marginalised race or ethnicity) is a hot debate among young fashion industry commentators today, and for good reason.

“You know, in the wrong hands, sometimes working class references can be fetishised or patronising or just used in a bad or wrong way,” said Kentros. “But if it weren’t for some talented British fashion people celebrating and showing off and revamping the style references they lived or saw in tough neighbourhoods in the Midlands and the North and areas of London, then we would never have developed a whole part of the fashion design palette.”

Yet some believe say that the working environment of the fashion industry is a much bigger and urgent problem to solve than any problems that exist around class appropriation.

Creative industries such as fashion “sell themselves as being open, informal and having spaces that allow people to celebrate individuality and self-expression,” said Sam Friedman, a sociology professor at LSE and author of “The Class Ceiling: Why It Pays to Be Privileged.” “The thing is, it’s a little bit of a myth when you delve into who works in those jobs and how the culture reflects their class backgrounds.”

This “culture” among fashion professionals manifests itself as social cues that tilt in favour of those from privileged backgrounds, and are therefore taken for granted and perpetuated as the industry remains closed-off to outsiders. As Creative Access Founder and Chief Executive Josie Dobrin put it, “privilege perpetuates privilege… It’s not just about the job itself; it’s about the environment.” A classic example of this is workplace chatter where colleagues “not only talk about what university they went to, but what college within the university they went to.”

Friedman refers to these modes of self-presentation as “studied informality.” Fashion, like media and other creative sectors, positions itself as a friendly alternative to the suited-and-booted corporate world, but these unwritten codes of behaviour — from hugs and kisses instead of handshakes to awkward conversations with PRs about one’s last summer holiday — can be just as daunting as more stuffy, traditional professional spaces.

Privilege perpetuates privilege… It’s not just about the job itself; it’s about the environment.

“These things can seem superficial, but they are very clearly classed,” said Friedman, citing some working-class creative professionals who described their experiences as “disorienting, intimidating and hard to navigate. As a result, they [can] appear to be ill-at-ease, or the classic term ‘lacking in confidence,’” making them less appealing to the employers who determine career progression. “Confidence is contextual,” he said. “Certain behavioural codes can embolden some but intimidate others.”

When it comes to redressing disproportionate representation of lower income recruits — or indeed any demographic — in fashion, there’s no easy answer. “It’s about outreach, making sure there are routes in,” said Dobrin.

Without these routes in, prospective applicants in more precarious financial positions feel pressure to find work in different, more (ostensibly) stable professions. Among designers, existing circuits of the fashion establishment are arguably losing their appeal, becoming an outdated — if not unwelcoming and insular — place for young talent to make a name for themselves, particularly as individual entrepreneurship becomes a more viable option.

But despite the many challenges they continue to observe and experience, young designers like Joseph and Saunders seem hopeful. “I do feel optimistic that this industry is changing and opening up,” said Joseph. “You don’t have to be aligned to some quaint institution or special club [anymore].”

Like Joseph, Saunders sees her working-class background as a credit — rather than a hindrance — to asserting herself in London’s fashion industry. Put simply, she said, “You can have as much money as you want, but you can’t create culture out of nothing.”

Related Articles:

[ A-Cold-Wall’s Class-Clashing Workwear ]

[ The Face Is Back ]

[ Can Burberry Get Back on Track? ]

[ Why Puffer Jackets Are at the Centre of Korea’s Class Divide ]