MILAN — When he remodelled the garden of his home in Milan, Giorgio Armani added a pavilion, a wall of bamboo and an imposing pair of Japanese maples, transforming an awkwardly inclined courtyard into the kind of spare, contemplative space you might find at the heart of a ryokan in Kyoto. The ideal spot, in other words, for a fashion samurai, a lion in the winter of his years, to sit back and quietly reflect on his achievements.

But Giorgio Armani isn’t that person. “I need to forget that I’m 88, otherwise it’s over,” he declares. “I need to try as if I started today, and this is a problem because when I wake up in the morning, I’m 88, which is very hard.” Even after all this time, with the global empire, the billions, the awards, he exists in a state of perpetual dissatisfaction. “I’m not satisfied, because I want my current work to be appreciated, not to have an award for what I have done, not to have an attestation for something passed. That’s what wakes me up every morning. I still need to prove myself.” He tells me that he has never dreamed so much in his life, two or three dreams a night. “Sometimes I dream of doing a beautiful fashion show and when I wake up, I’m so angry because it was only a dream.” Even in sleep, he is pursued by dissatisfaction.

We are sitting in a room adjacent to the garden, with his assistant Paul and translator Anoushka. At one point, Armani says he likes my accent (“Australian-British” he calls it, only 1300 miles off). “It makes me really suffer that I can’t speak English. I would have loved to learn it.” But I’ve always been struck by how direct he is in interviews, and I assume that’s because he is able to express himself with complete clarity when he is speaking in his mother tongue. On the wall is a massive work by the Italian artist Silvio Pasotti. It’s a surrealistic melange of fashion history, designers, models, magazine covers collaged with iconic images like the Helmut Newton photograph of Karl Lagerfeld in a black bathing suit. He sprawls insouciantly across the bottom of the painting. That’s not the only time he’ll appear in this story. Next to him, in the left-hand corner, Armani sits looking back over his shoulder at the artist. He’s shirtless, sexy in denim shorts and Pasotti has tattoo-ed a Lacoste crocodile on his shoulder. “Because that was the time of Lacoste,” the designer laughs.

We happen to be talking a week before Armani shows his Spring/Summer 2023 collections for Emporio and his own line. His workload remains unchanged. I ask him how each season starts for him. “With a blank piece of paper, and my hands in my hair,” he says ruefully. “Then I take away what wasn’t good in the past. And I look at what’s happening at the moment. I look at my colleagues’ work. Sometimes I’m positively surprised, many times negatively.” Armani is notoriously judgemental. At the moment, he’s not positively surprised. What does he look for? “Where the novelty is, what exists of the fashion of the time that still can be right for today.”

But when “today” is defined by a war, a pandemic, rampant political and financial instability and, overriding everything else, environmental catastrophe, what exactly is “right”? The war in Ukraine has hit Armani hard. He has his own childhood experience of WWII as a reference. He grew up in Piacenza, a small city to the south-east of Milan, and he has vivid memories of taking refuge in the local movie theatre during Allied bombing raids. When he was nine, he and his friends found a bag of gunpowder. While they were playing with it, it exploded. He spent six weeks in hospital on the brink of death. Legend has it that the skin on one foot still bears the imprint of his shoe buckle.

“When I look at the news and I see the images of suffering, it feels like what I’m doing doesn’t make sense nowadays,” Armani says. “This is where it’s difficult for my job, but I need to beat this feeling, this sort of brake that I have that doesn’t enable me to create. I have an example, the recent women’s show, the one I decided to show without music. It was just a few days after the war had started, I did a press conference in this room. I was asked about fashion and in that moment, I just couldn’t speak about it.” Anoushka interjects, “I was there so I can honestly say, Mr. Armani started crying.”

I doubt Giorgio Armani sheds tears very often. For nearly 50 years, his major motivation has been this: “It’s important to not live off nostalgia, to not be doing anything gratuitous, and, most importantly, to innovate, but always keeping in mind that you need to try and make men and women comfortable, feel good in the clothes. Never forget that’s the prime purpose. I can help better my customers’ lives in this way.” That’s also been his consolation through the most difficult periods of his life.

It is a challenge to appreciate how a proposal which sounds so benign now was so radical at the beginning, Armani recalls, “that not everybody understood, because even then, fashion was trying to do something explosive, not necessarily to be comfortable. But then slowly, people understood that my proposal to make fashion more acceptable was the right thing to do.” It’s almost as if he was more reactionary than revolutionary, taking a stand against the extreme proportions, the extreme hairstyles, the extreme everything of the late 60s and early 70s. And then, ironically, reaction bred revolution.

The Pasotti painting on the wall behind us dates from 1978. Armani’s business was barely three years old at that point, but the artist already saw fit to include him in the fashion pantheon alongside Chanel, Dior, Balenciaga, Saint Laurent and the other immortals. He instantly became part of history when he de-stuffed fashion as radically as his idol Coco Chanel had done half a century earlier. But that same history has a tendency to rub the edges off a revolutionary and seal him in the aspic of his past achievements. Armani says he’s happy I think of him as a radical, even happier that I don’t call him nostalgic. “My big fight is with time,” he says, and when time is the enemy, you don’t want to indulge it.

And yet, he can make it sound like there is something vaguely liberating about time passing. He talks about feeling more detached with age, less anguished, maybe more cynical. “I find certain things absurd. Sometimes I think the designer is just too much in his own world of trying to propose something which has to be on covers or that needs to shock, rather than really thinking of the purpose of his job. When I see fashion trying to be in the news just for novelty, I find myself quite shocked, so I become even more cynical. I don’t believe in it. Even when they talk about my things, when I make something a bit outrageous and they say they sold it, I don’t believe them. You know, there may be one hundred people around the world that like something extravagant, but in normal life, I don’t believe in it.”

What about Armani’s use of the word “novelty.” Does he believe it’s possible for anything to be really new in fashion? “No, but maybe you can find a new way to adapt something that has already existed to today’s context, so you find a new way to propose something.” What he really hates is the determining force of “fashionability.” Again, I wonder if such a thing still exists. “Si, certo,” he says instantly. “You just have to look around you and see how some people dress, and they are all following a certain thing that’s of the moment. They all look the same.”

Armani describes himself as isolated, not social, a slave to his job. “But it’s different to before. Now there’s a real empire behind me that I need to preserve for later when I won’t be here anymore.” This is, of course, the succession plan that drives the fashion industry crazy with speculation, because it is so shrouded in mystery. Not to mention that Armani-branded products generated €4 billion in 2021. Rumoured overtures from Bernard Arnault’s LVMH, the Agnelli family’s Exor and Mayhoola, the Qatari investment fund that owns Valentino, are maybe just that. Rumours. “Forgetting what’s happening in the rest of the world, that’s how I plan,” Armani says cryptically. “That’s why I’ve isolated myself. To know what’s the right thing, not following the road that I don’t like. You know, it is very simple. Say no.” One thing that is telling is how much Armani values his independence. And that’s something he would really like to guarantee.

The Bloomberg Billionaires Index estimates his personal net worth at $9.5 billion, making him the richest fashion designer in the world, and he has clearly sacrificed for that success. Armani often maintained that if he could live his life over, he would do things differently. “Yes, I would still change certain things,” he says today. “I realised I don’t really have friends, aside from my close family and people in the company. With friends, you need to cultivate them, you need to provoke them.” In other words, he has done neither. Years ago, Armani told me he never wanted kids because he thought he would be “an envious father.” I assumed he meant he’d be over-protective. But I’m wondering if he feels like he missed out. I’m telling him something Karl Lagerfeld said towards the end of his life — how he’d found he could feel real love, for his cat Choupette, for Hudson, the young son of model Brad Kroenig — and Armani suddenly sparks up. “Yes, incredibly for me too. It’s different now, you’re absolutely right. For two years, there’s been a little child running around these offices, the daughter of one of my close collaborators. She has become love, and for the first time I have found a vulnerability. I’ve never had this sort of love. It has made me different. I’ve found my tender side.” In a coincidental twist, Armani is also very attached to his cat.

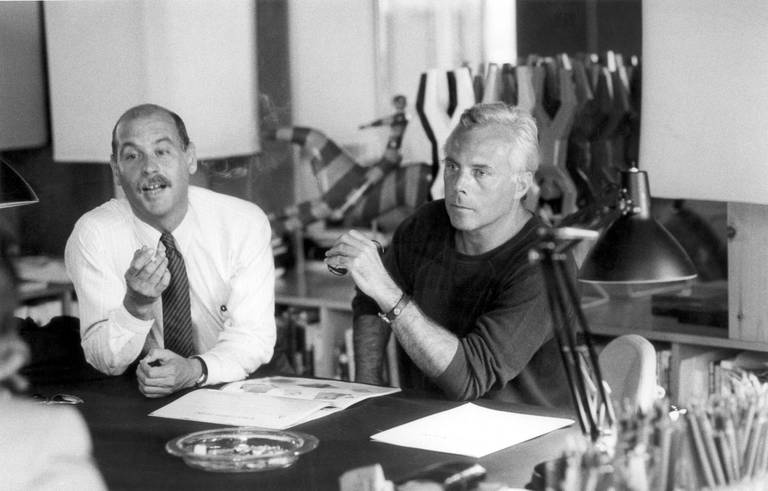

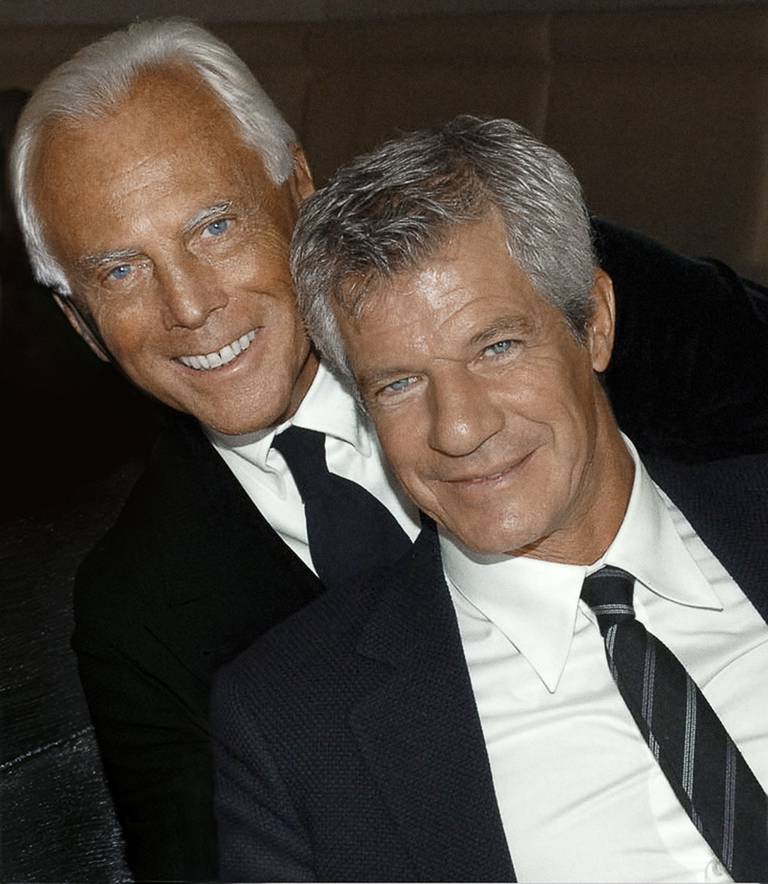

Giorgio Armani, happy at last. But he learned a long time ago not to trust that feeling. When he started his company, there were two: Armani and his partner Sergio Galeotti. They met at the beach in 1966, when Armani was designing menswear for Nino Cerruti. Galeotti, 11 years younger, had the innate sense of superiority all Tuscans possess (according to other Italians) and it was his drive that pushed his older lover to go solo. He made him sell his Volkswagen for money to seed the fledgling business. Armani remembers those early days, creating something with someone he loved, as “indescribable joy. There was a thrill and an enthusiasm. Sergio was explosive, he was much more courageous than me.” He laughs as he looks back. “Sometimes he forgot his conscience, sometimes he was a little bit too much.” He considered Galeotti his alter ego. That’s how people remember him, ferocious, sardonic, very driven, but also very entertaining. “It was a nice balance between me being more held back and Sergio being more brave. And maybe it happened because we weren’t even really aware of what we were building together.”

In 1984, Galeotti was diagnosed with AIDS. He moved to Paris, to be near the Pasteur Institute, where Luc Montagnier was making early breakthroughs in the understanding of HIV. For 12 months, until Galeotti’s death in August 1985, Armani shuttled between Milan, Paris, New York, and everywhere else their rapidly growing business needed him. “I had to go on with the job, I had to design, but I had to be close to Sergio. It was the worst year, though actually, at the time, it was step by step. I didn’t really think what was going to happen. I definitely didn’t think I could make it by myself.”

And neither did anyone else. It was widely assumed within the industry that Armani would simply retire. But he is a Cancer and “a crab gathers everything to itself,” he says. He found a new self-determination after Galeotti’s death, absorbing his alter ego, moving forward with sole control of the business. When I suggest that the whole Armani edifice is a monument to Galeotti, he agrees. “In a certain sense, yes, because he gave me the strength. Everything really started with Sergio, and if I didn’t have the strength to react as I did, this company wouldn’t exist. So, yes, it’s due to him.” Does he ever wonder how it would have looked if Galeotti hadn’t died? “I think Sergio would maybe have made Armani a little bit more revolutionary, a little more explosive,” he muses. “I’m very practical, he was a dreamer.”

But then, Armani interrupts his chain of thought. He wants to acknowledge another individual, Leo Dell’Orco, who has worked for the company since 1977, and is currently head of the Men’s Style Office. (Armani’s niece Silvana is his counterpart in the Women’s Office.) “After Sergio’s death, he has been the closest person to me,” Armani says. “He gave me an incredible psychological support, practical as well as workwise. Primo Sergio, poi Leo.” Successionists might want to file that name away for future reference.

But his acknowledgment of Dell’Orco also validates that vulnerability Armani was talking about. He seems more open. He looks more relaxed in photos. Remember all those moody monochrome press shots from earlier decades, with Armani idealised as if by George Hurrell in Hollywood’s Golden Age. They actually made sense, because one of his original ambitions was acting. Paul Newman was an inspiration. It’s an irresistible notion that he’s been playing a role all these years: Giorgio Armani, superstar designer. “Yes, a little dose of acting is part of my job as well, isn’t it?,” he agrees. “It’s not that I’m not natural, I stay true to myself. But I have to be a bit more. The people around me expect me to be a certain way, so I do have to act a little.”

Elements of the act have attained a certain notoriety over the years: Armani, the hard taskmaster, so demanding that former employees still wake up years later in a cold sweat thinking they haven’t finished something they were supposed to do. Is it an act or an extension of his own conflicted dissatisfaction? Armani himself insists that he tries not to let himself be seen as “a usurper, someone who takes advantage of people”. He hopes that his reputation is as “a kind man.” But he also once told me that his reputation was like handcuffs. And, professionally at least, his opinion hasn’t changed. “People think of me in a certain way and doing a certain type of fashion.”

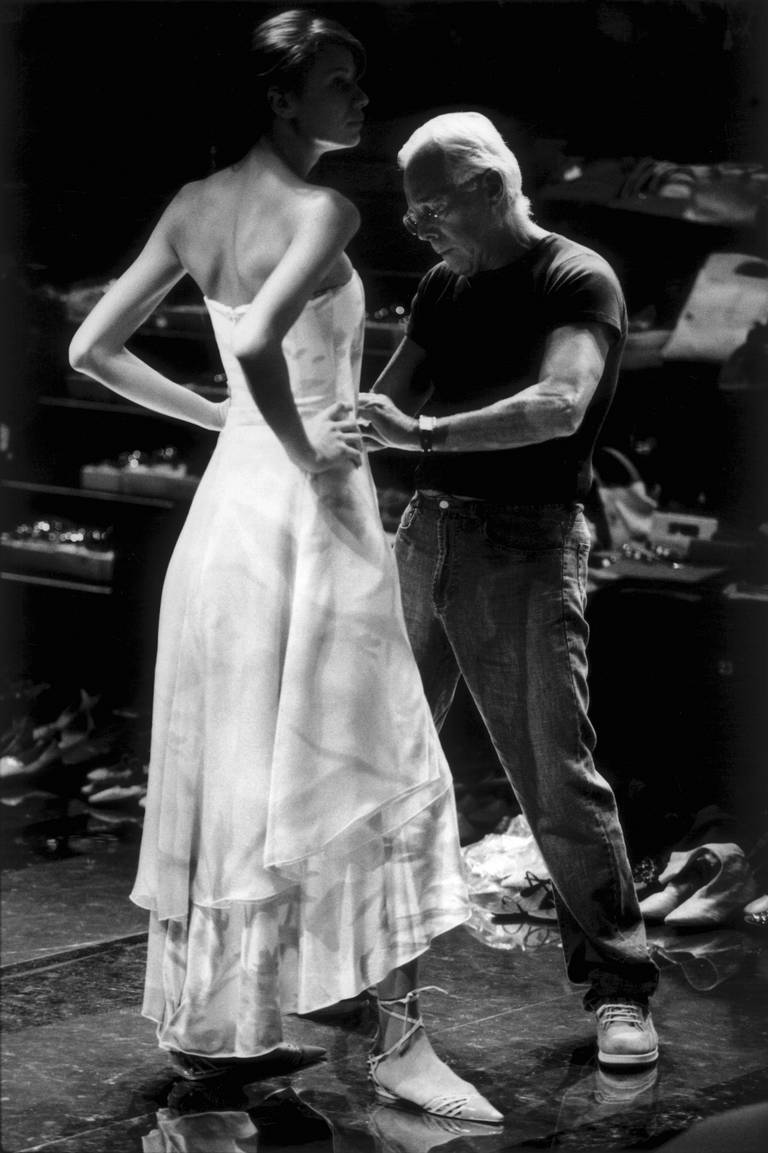

Which rather begs the question of how Armani would like to be remembered. He takes a long pause before he answers, “…as a sincere man. I say what I mean.” That seems like a humble response from a man who rules a huge fashion empire. “Unfortunately,” he says with another easy laugh. “I am an emperor who doesn’t feel like one.” It must mean something that the part of his empire that Armani still finds most engaging is his fashion shows. “When what I decided in my head comes out on a model, and it corresponds to what my idea was, it’s very gratifying. No one else exists in that moment. It’s very intimate. It’s not a contract, it’s not signing something.” A few days later, I’m backstage at Emporio, and I witness the astonishing sight of Armani working his way down a lineup of models, minutes before they go onstage, hands on to the very last second as he adjusts the eye makeup on every single young woman to create a scintilla of light.

For years, Armani’s clothes were so identifiable by their neutral tones he became known as the King of Greige. The sobriquet riled him. Then his collections became as distinctive for their evocative shades of blue: sea and sky. More recently, light is the key ingredient. Armani called his last haute couture collection Petillant, “sparkling.” The weightless fabrics of his ready-to-wear collection for Spring/Summer 2023 shimmer with gold and silver, counterpointed by luminous evening shades of blue and purple. It may well be more a reflection of my own needs at the moment, but I’m detecting a spiritual thread in this glimmer of the great beyond. Armani gives this some thought. “With age comes a certain detachment from the materiality of things, but also from the hustle and the bustle of work. I care less about other people’s opinions, and never cared about trends. I keep doing what I do, and I keep purifying the output. Would I call that spiritual? Probably not. Spirituality is something very private, while clothes are objects. But for sure, everything I do now is pure and it has more light. It reflects my condition of existential lightness, which of course hides a certain gravitas.”

That very much sounds to me like the musings of a lion in winter, in light of which my last question is obvious. Does Armani ever think about what happens next, not for the business but for himself? I don’t actually expect him to answer, but he does. “For the time being, I keep thinking about work and life, not fantasising too much about the afterlife. That is something that I keep for the deepest recesses of my thoughts. I am sure that, when it will happen, it will be a surprise.”

Decades ago, Armani bought a house in his hometown Piacenza. It was near a park filled with beautiful trees, and he once told me that he wanted to give a name to every single tree in that park. “And when a tree dies, something in me dies too.” Now that was a surprise. His connection with nature felt so poignant to me that I have to bring it up again, while we’re sitting looking at his beautiful Japanese maples. “No, I don’t remember that,” Armani says. “It’s nice. It could have happened.” I guess anything can happen. And it will always be a surprise when it does.

Giorgio Armani has been a member of the BoF 500 since 2013. Explore the BoF 500 community here.