It’s December 2021. We’ve been through 18 months of grief, fear and disruption. Just as life is beginning to return to normal for many, warnings of a sinister new variant spread. People are searching for reassurance, distraction. Or, failing that, just something that doesn’t have its own designated horseman of the apocalypse.

Wordle comes along at the perfect time. Its creator, Josh Wardle, a software engineer living in Brooklyn, invented it that summer to entertain his partner, Palak Shah. It’s a simple pleasure: there’s a hidden word and, using powers of deduction, you have six attempts to figure out what it is. The game was never intended for public consumption – it was only after it became a hit on the family WhatsApp that Wardle began to think it might have wider appeal. And, sure enough, by the end of the year millions were playing and sharing their results on social media. It spawned a Spanish language version, then Arabic, French, Swedish and Japanese. It inspired joyful imitations: Worldle, where you have to guess a country from its shape; Emovi, where you have to figure out the film from a plot sketched in emoji. Key to all of them was a mechanism that acted as a counterweight to our hyperactive online lives: there was only one round a day, and the solution was the same for everyone.

I remember this ripple of delight reaching the normally sober newsroom where I worked: one day the Guardian turned over its entire morning conference – the forum where we discuss the (frequently grim) news of the day – to Wordle. I wrote a piece on how knowing the sound patterns of English words can help you crack the game, and I’ve never been more in demand – admittedly the bar is low – getting requests to talk on radio shows around the world. When the game was bought by the New York Times for a seven-figure sum, we all worried that its uncommercial nature might be under threat: so far, at least, it remains free to play. But regardless of the fate of his creation, Wardle seemed to have opened up new possibilities for enthusiasm and creativity. Innocent fun was back in vogue (not, I suppose, if you count the sweary spin-off, Lewdle). And while the New York Times might own Wordle, it didn’t own fun.

So it felt inevitable, somehow, when one day an editor on the Saturday magazine, Will, made his way over to my desk. “Why don’t you have a go?” he asked. “At what?” “Inventing a game. A new Wordle.” “But I’m not even that good at the original.” “Didn’t you just write a piece called How to win at Wordle using linguistic theory?” he asked. He’d got me. With Wardle’s millions in my mind, I asked if I would be able to keep the royalties. Will explained that I would be doing this on Guardian time, and my reward would be furthering the cause of investigative journalism. Oh, go on then. Some things are more important than money.

It sounds easy in theory: come up with an idea for a game, simple but strangely addictive, get some tech geniuses to build it and – hey presto! – global fame, a slew of imitators and radio appearances coming out of my ears. The only problem was, well, I’m not the world’s biggest puzzle person. I’m bad with numbers, so I don’t like the mathsy ones. I hate anagrams. Countdown? The worst of both worlds. General knowledge is my thing: I stew in facts and have bizarre recall for the minutiae of a select few specialist subjects. Which is before you even get to my total lack of experience in the principles of game design, product design, anything design really. OK, it’s true I studied linguistics and wrote a book about how language works, but that and having a journalist’s inflated sense of my own abilities might not be enough to propel me over the finish line this time. I decide it would be useful to talk to some experts first.

Oliver Roeder fits the bill: he’s a graduate in economics and a former competitive Scrabble player – peaking at 223rd in the US – who now works as a data journalist. His book, Seven Games, charts the history and mechanics of chess, Go, backgammon and bridge, among others – the most enduring creations in humanity’s history of play. So what is the secret of their success?

“There’s a lot of randomness in it,” Roeder tells me. Partly, it’s just what has survived, through luck or the vagaries of history. “But I think there are some hurdles a game has to clear, like replayability. If a game is going to last 1,000 or 5,000 years, it better be interesting enough for you to be able to play it a lot of times without getting bored.” Another important factor, Roeder argues, “is a very healthy balance between luck and skill”. Luck levels the playing field: a genius can roll the dice in backgammon and still find themselves at a disadvantage. But skill is vital, too, as it brings with it a sense of agency: “The feeling that you’re in control, the feeling that what you do matters.”

The same applies to puzzles, he says. The element of chance in Wordle is your first go, which is necessarily a crapshoot (that’s a dice game, by the way). The skill comes in what you do next: how you use your knowledge of the lexicon to refine your guesses. So, does he rate it? “It’s interesting how much it caught on, because it’s a very unoriginal game,” Roeder says, stressing that he doesn’t intend any criticism here, as there’s rarely anything entirely new under the gaming sun. As many have pointed out, Wordle is basically a lexical version of Mastermind – the game beloved of 70s and 80s family Christmases where you have to guess the sequence of coloured pegs hidden by your opponent. But the format isn’t necessarily what makes it special. “The genius is twofold,” Roeder says: first, the fact that there’s only one word a day. That means everybody’s talking about the same thing. Then there’s the widget you can share on social media – a little grid of coloured squares that gives a readout of how you did. “It’s instantly recognisable and avoids spoilers in a very clever way. That communal part of it I thought was brilliant.”

I note this down. Anything I do has to be collective, and shareable. Wordle worked because it replicated the sociability of games night (without any danger of infection). It brought back the “water cooler” moment – giving a huge audience the same hook on which to hang its frustration and joy. But it’s also a solo game – so what is it about the individual experience that works?

Clara Fernández-Vara is a professor of gaming and a ball of nerd-energy. She talks to me from New York, where she teaches the next generation of designers at NYU’s Game Center. What she finds fascinating is the way Wordle has become part of so many people’s daily lives: “It is like a ritual,” says Fernández-Vara, who sees the game as occupying the same niche as crosswords. “There’s the little pleasure of being able to solve a puzzle, when the rest of the world is overwhelming. It can be a way of meditating, of escaping, but more than escapism it’s control – these are problems we can solve.” A popular game needs to be something you can sneak into the nooks of the day, as a little bit of respite. “I do Wordle while I’m waiting for my son to finish his breakfast. And at times I start and feel stuck, I leave it, and another five minutes later I think of the next word.”

So far, so everyday. But there’s a bit of magic involved, too: what Fernández-Vara calls “entrancement”. That powerful, hypnotic quality shared by the most addictive games. Can she give me an example? “Tetris!” she exclaims. “It’s easy to pick up, but it keeps you going and going.” The appeal of the basic concept is so strong – you arrange falling blocks of different shapes so they fit snugly together – that it transcends anything as distracting as rules. “Back in the day, my aunt got a copy of Tetris, but she never read the instructions. So she didn’t know she could turn the pieces around, but she loved it. She was playing it for three months. When I told her that she could turn the pieces, that broke her brain.”

Luck. Skill. Something communal, yet intimate. Entrancement. OK, so these are the fundamentals. And it also needs to be something I’ll enjoy creating. Did I mention I hate numbers? That rules out anything like Yahtzee or sudoku. A completely abstract game like Tetris, while addictive, seems too divorced from the wider world. No, it’s got to be word-based. Maybe I could compromise, though … I begin to have visions of blocks of letters falling across the screen. You pick out a word, horizontally, diagonally, maybe backwards, then – ping – it disappears, making room for more. That’s not bad! I write down “Scrabble Tetris”. Genius. Perhaps not the easiest thing for our software engineers to code. And there could be one or two intellectual property issues. What price might Big Game exact from us if we threatened their hegemony?

I need to calm down and think methodically. There’s the issue of data, for example: in any game that uses words, there’s got to be a list that tells you what’s valid and what isn’t. Scrabble has an official dictionary, with 192,111 entries. But it doesn’t list words longer than 15 letters, the width of the board. There’s the Oxford English Dictionary, of course. And that has the advantage of containing lots of additional stuff about dates, etymology, examples of usage, etc. Maybe there’d be some way of using that?

Which brings me to my second idea. Linguists sometimes talk about the “recency illusion” – the tendency we have to think that certain words or usages are newer than they actually are. One good example is “doable”, which sounds very contemporary. But if you look it up in the unabridged version of the OED, you’ll find that in 1449 Bishop Reginald Pecock wrote about “a lawe … which is doable and not oonli knoweable”. Or there’s “high”, as in “under the influence”. A character in a 1607 play by Ben Jonson refers to being “high with mirth, and wine”. Since every entry in the OED comes with the date of its earliest recorded use, perhaps that could be the basis for our game? So, you start with four or five words, and your task is to drag them around the screen and put them in order of age. Oldest first, newest last. The results would be revealed and you’d either be like, “Huh, I never knew that” or, “Wow, I have a hitherto untapped capacity for correctly guessing the age of words.”

Feeling pretty pleased with myself, I speak to one of Fernández-Vara’s former students, Sam Von Ehren. He’s freelance now, but used to design games for the New York Times, working on the newspaper’s popular Spelling Bee. First, what does he think of my date game? “Nice,” he says, before admitting, “We actually had a very similar idea, with crossword clues. You had to put the order they appeared [in the newspaper] by date.” This is a good example of making use of a dataset you already have – but it’s hard to imagine crossword clues age in any very obvious way. That was the problem, Von Ehren says. “We only go back to the 90s,” so it’s not like there would be old-timey turns of phrase that would give away a clue’s vintage. “We did play-test it, and it was fun when it was good. Then really annoying when it was not good.” The flip side of the huh-I-never-knew-that reaction is the how-the-hell-was-I-supposed-to-know-that one. “That’s the thing you have to be careful with. Feeling like you’re getting cheated.”

Oh, and Scrabble Tetris? Von Ehren says it already exists in the form of something called SpellTower. But I shouldn’t feel too bad: “It’s kind of a joke that it’s not really worth trying to be truly original in game design.”

In any case, coming up with a concept is one thing, but it’s in showing it to others and adapting it that a game gets good. “I think having people play around is 10 times more important than the idea,” Von Ehren says. “The things that people love the most about games were never part of the original.” This is something he learned at NYU, where the first stage of creating a game was called “paper prototyping”, where “you literally make a version of the game using just pencils, paper, pieces from other board games, or whatever”. You put it in front of someone and see how they get on – what obstacles they come up against and, crucially, whether they have any fun. The “lightbulb” moment I have been chasing – the flash of inspiration in which a game is conjured in my head fully formed – is a fallacy.

Or is it? What I’d learned so far was that thinking hard about what kind of puzzle could possibly rival Wordle wasn’t helping me very much. The pressure was too great. Games are intrinsically playful, and high expectations aren’t conducive to play. What is conducive is needing a bit of distraction – a low-stakes alternative to duty, to deadlines, to matters of life and death.

That’s where my older brother, Daniel, comes in. While I’m racking my brains about how to come up with a better version of Boggle, he’s with his partner Nic in a hospital waiting for their baby to be born. On the morning she is due for an induction, they arrive bright and early at 8am. I call at about 11am to see how things are going. “What about if you had a word,” Daniel says, “of three letters – and the point of the game is to find the longest word that still has those three letters.”

“You mean like an anagram, but you make it longer?” I ask, confused.

“No, you’ve got to keep them in order. So if you had ‘bid’, then maybe, er, ‘forbidden’ would be the longest word.”

“Or ‘ambidextrous’.”

“Right.”

This is typical. I’ve been thinking about this for weeks. Daniel is supposed to be having a baby today and instead he’s come up with something that just might be the next Wordle.

“I think that’s pretty good,” I tell him.

“Yeah, OK – gotta go.”

“What about the bab – ”

I’m not resentful that the lightbulb didn’t go on in my head. My brother has been on hand with answers to my questions ever since I learned how to ask them – I basically consider his brain a handy extension of mine. In a way, Wordle was the product of a family collaboration, so I’m happy for this to be as well, and the unwitting involvement of my unborn nephew (Rowan, now six months old) may yet go down in history. In any case, there’s still plenty to figure out before it becomes a fully fledged game: how we score it, what words we include, how many goes you get, what does it look like and so on. That’s my responsibility.

And at least I finally have two half-decent ideas to take to our first development meeting. This involves Will and various people from our digital teams. Still quite proud of my guess-the-date idea, I explain that one, to various mildly approving nods. Practical questions come up: how easily can we scrape etymological data from the OED? Would they give it to us for free?

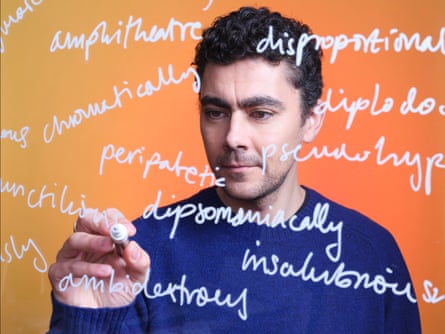

Next, I pitch the longest word game: “So if you have a word like ‘pit’, you could have ‘spit’, ‘spittoon’, ‘hospitable’.” “Amphitheatre!” Will exclaims, triumphantly. There’s a beat before we realise it doesn’t work. But I can hear an excitement in his voice – pride at having swung even if he missed. Maybe there is something to this. We do a paper prototype, and decide to play it against the clock – 15 seconds. I call out the word “cub” and everyone scribbles furiously. Time’s up before we know it, and all I managed is “scuba”. Someone gets “incubation”. Will has “cubism”. “You know what?” he says. “It’s a good game!” Entrancement? Unlocked. Well, possibly.

Given that this meeting hasn’t been a total disaster, I am assigned two brilliant young minds who usually spend their days designing new tools to help make journalists’ lives easier – widgets that help us publish articles, edit homepages or select pictures from a vast library, for example. They are developer Freddie Preece and Ana Pradas, a product designer. Together we’ve got a few months to build the game – in our spare time. Within a day or two, though, Freddie has come up with a working version, on an actual computer. It’s bare bones, just code rippling down the screen. It uses a traditional dictionary to generate a starter word. You type in your guess, then the longest possible word is revealed. We quickly abandon the idea of doing it against the clock, as some starter words are going to be much harder than others, and people might want to dip in and out, like Fernández-Vara does with Wordle. But there have got to be some constraints – so we decide to allow five guesses only, with a new starter word each day.

Sounds straightforward, right? Except that we immediately come up against some seriously head-scratching issues. Underpinning everything in this game is the wordlist: it defines what’s allowed as a guess and what the longest word is. That demands a dictionary that is both comprehensive and free. That’s what we’ve been using – but we quickly discover that comprehensiveness has its downsides. Take the word “dip”. You might guess “diplodocus” or, on a good day, “dipsomaniacally”. But are you really going to come up with “dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane”? Well, you’d better, because it’s in there. Imagine how you’d feel when you discovered that this was the word you’d been expected to guess. (Exactly: how the hell was I supposed to know that?)

A brief interlude, because these feelings are important. The sense of disappointment comes about when you violate the crucial “challenge-skill” balance, explains Joydeep Bhattacharya, a professor of psychology at Goldsmiths, University of London: “If the challenge is too much, you get frustrated. If the challenge is too low, then you’re literally bored.” If you can find the sweet spot, on the other hand, then you’ll have something that passes the time. But there’s got to be more to it than that. “You should be intrinsically motivated, interested in the activity,” Bhattacharya says. That’s why people don’t get addicted to washing dishes. “When the two conditions are met, we get absorbed. We might also have this flow-like feeling, and we are more likely to come back to it because it’s also intensely rewarding.”

What’s at the bottom of this rewarding feeling, though? For Fernández-Vara, it’s almost like scratching an itch. “Puzzles have a gap, something that is missing,” she says. “And most people feel the compulsion to fill it. There’s something kind of unnerving about seeing a puzzle, seeing that gap, and we have to tackle it.” Filling the gap, she explains, leads to “the aha moment, the eureka moment: ‘I got it and that feels good.’ It’s a little high.”

Bhattacharya describes “aha” – yes, that’s it’s official name – as “a kind of pinnacle of human cognition”. There are four components to it: first, unpredictability – you don’t quite know how, but the solution just snaps into place. “You get a kind of clarity, which you didn’t have just beforehand.” Second, when it happens, you’re totally convinced it’s right. “You are very certain the moment you get the solution; you don’t need to check.” Third, there’s a sense of it having fallen into your lap, without much effort. And, finally, it’s highly pleasurable. “We found that there is a very distinct activation of dopaminergic brain networks whenever we get this ‘aha’.” These are among the networks also activated by addictive drugs such as cocaine. The effects of this activation are complex, but Bhattacharya says they serve to make the experience seem important, as well as helping you to remember it. Our game will hopefully offer five small ahas, one for each time you correctly guess a word, with the possibility of a huge aha if you get the longest one. Alan Partridge would be proud.

It makes sense that we evolved to experience solving a problem this way, as in the real world it can mean the difference between life and death. Roeder traces a path between this addiction to problem-solving and the very invention of games. “We have to hunt to get our food, and we could approach this problem a number of ways,” he says. “We could hunt all the time, but this would be really dangerous. We could never hunt, but this would also be bad, because we wouldn’t get any good at it. Or we could find the middle ground, which is to invent a game to practise where we throw rocks at a tree, or whatever. And maybe games are actually this really important evolutionary development, where we practise the essential elements of this dangerous thing we have to do.”

Back to the problem of the dictionary. “Pseudopseudohypoparathyroidism” is a great word – fantastic, even – but if our wordlist says that’s the longest one you can make using “pop”, and you merely guessed “unpopularity”, you’re going to be annoyed. In other words, we need some way of excluding thousands of chemical and medical names. Freddie, whose calm demeanour belies a brain that whirrs at least three times as fast as mine, comes up with a possible solution. He found it on a website called Scowl (that’s Spell Checker Oriented Word Lists, in case you were wondering) and it’s a dataset called 3of6game. Its creator, Alan Beale – seemingly out of the kindness of his heart – scoured six dictionaries carefully balanced between British English, American and international sources, and homed in on the common core: words that appear in at least three of the six. That gives you pretty wide coverage (64,000 words), but also weeds out a whole load of incredibly obscure terms that a single dictionary such as the OED would have to cover.

This feels perfect. We’ve melted English down to a solid nub of precious metal – words that everyone should know and that are agreed across continents to be valid. It feels perfect, that is, until you try to play it. By now, Freddie and Ana have magicked up a version of the game you can use on your phone. It’s lovely, elegantly designed in Guardian colours, with a bona fide aha at the end when the longest word is revealed. When it’s a word you recognise, even if you didn’t get it, there’s a rush – an incentive to do better next time that something like pseudopseudohypoparathyroidism definitely doesn’t provide.

Sharing it with friends and family prompts delight but still occasional frustration. I get “age” as a starter word and play “overeagerness” (the key to getting the longer words seems to be thinking beyond the obvious syllable boundary – you’ve got to remember that it might not sound anything like “age” when it’s deeply embedded in another word). But the computer says no – or, rather, “not in wordlist”. Friends complain that “crushingly” is not allowed and point out that, rather sinisterly, you can have “waterboarding” but not “surfboarding”.

So 3of6game, despite its advantages, is excluding too many words. We’re never going to get a wordlist that’s beyond reproach – witness the number of people who complain about Spelling Bee’s rejection of their perfectly decent guesses – but we want to make it as good as possible. Freddie comes up with a hybrid strategy, using a comprehensive wordlist – meaning that overeagerness and crushingly would be accepted – but knocking out any longest words that don’t appear on 3of6game.

Scoring is another vexed question. How can we make sure people feel rewarded for the guesses they do make, as well as keeping that element of striving after the longest possible word? We settle on something that recognises both: you get a percentage, which shows how close you got to the longest word (if that’s 10 letters and your best guess is seven, your score is 70%) and a letter total – so five guesses of seven letters each would give you 35.

Enough of the nitty-gritty, though. If playing’s the thing, we need to get some people actually having fun with it. Of course, we’ve all been passing it around among people we know and practising in the office, but something more systematic is needed. Ana sets up a bit of market research via a site that records people’s responses as they play. We get sign-ups from the US, Canada and Britain; men and women; young and old.

What we end up with is a bunch of little videos that show users’ screens while they’re playing, complete with their narration in real time. They get the following instructions: “Imagine you have just found a new word game. You have to think of the longest word possible that includes the word given at the bottom of the page (for example, it the word is ERA, you could have words like intergenERAtional or ERAsable).” Jada from Georgia seems to like it. “This is different, this is something I haven’t seen before,” she says. She gets “gal” as the starter word and, off to a brilliant start, goes for “egalitarian”. Next she tries “Galatians”. A proper noun, so not in the wordlist, but she takes it in her stride. “Galactic” works. And then she gets a bit stumped. After umming and ahhing for another couple of minutes, she decides she is all out of “gal” words and presses “give up”. The longest word is revealed as “egalitarianism” – so close! “Ha! I was almost right!” she says. “That was kind of fun!” The feeling that she was within touching distance is what makes her want to play it again.

It’s hard to convey how weird and exciting it feels to watch a stranger play a game – a completely new game, one we’ve built from scratch – and get a buzz out of it. It’s something I see again and again over the coming weeks, as we try different designs, make tweaks to the rules, fiddle around with the instructions and the “scorecard” people will be able to share on social media. In the part of the building where we make the Saturday magazine, it’s increasingly common to see huddles of people crowded around a single screen, shouting out guesses, letting out little cries of disappointment or triumph.

We did it. But there’s one last problem: we still need a name. For a while we have a working title – Wordstretcher – that I become quite attached to. But then we find out that it already exists – which means a thumbs down from the lawyers. The race is on to find a name that’s original, memorable and means something. Letterama, Wordsworth and Wordstacker are candidates at various points. But things beginning with “word” are often taken, so, ever the smartarse, I try to remember what the Greek for word is. It’s lexis. How about Lexathon, then? Sounds a bit … gruelling. My boyfriend comes up with Lexpander, but I think that sounds too much like Alexander. Lexpandable – how about that? It’s like Wordstretcher, but with a tad more – how can I put this – tofu-eating wokerati edge? Not everyone is as enthusiastic: eventually, Wordiply emerges as the most favoured, legally unimpeachable candidate. When higher-ups sign it off, I feel like smashing a bottle of champagne against the computer as we launch our little puzzle and watch it glide majestically down the slipway.

Wordiply isn’t perfect. There will be missing words, technical glitches, things that annoy people. But it does feel as if it’s destined to have a life of its own: it’s been born and is no longer entirely ours. From this point on it belongs to the people who play it, rather than me, my brother, Freddie, Ana or Will. And that’s entirely as it should be. I hope you enjoy it – because it’s your turn now.

Play Wordiply: