The art-fashion-research collective CFGNY is “Concept Foreign Garments New York,” but also “Cute Fucking Gay New York” and, once, for a Berlin exhibition, “Certain Forgotten Gestures Near Yourself.” The acronym functions, like the concept of “vaguely Asian” that is central to the collective’s work, as a kind of playfully ambiguous signifier: context-dependent, constantly in flux, open to the joys of mistranslation. Their most recent collection, Fashion Max 2, was staged this past Saturday at Japan Society’s Midtown headquarters, a Junzo-Yoshimura-designed masterpiece of architectural diplomacy: Western modernism X classically “Japanese” aesthetics. There’s a waterfall, a rock garden, a rippling pool, light that pours diagonally down a flight of stairs. CFGNY’s clothes are similar: collage-like assemblages of diverse materials and textures, often printed with patterns of syntactically exotic scraps of language. As I watched CFGNY’s models—a cast that included artists, chefs, and a real-estate-agent-slash-dry-fish-importer—circulate coolly over a makeshift wooden walkway, the presentation struck me as a vaguely Asian rejection of classic runway tropes. There was no catwalk, no spotlight, no glamazon supermodels, only a multidirectional flow of what might be neighbors, passing each other on the stairs, lingering on a bench, pausing sometimes to perform a series of gestures that recalled glitched-out tai-chi, or flowers unfolding in timelapse, or maybe just people living a language that you don’t understand but that is beautiful anyway.

The show was presented alongside “Refashioning,” an installation of video and sculpture that showcases both CGNY and fashion label Wataru Tominaga, up at Japan Society through February 19. I talked to CFGNY founders Daniel Chew and Tin Nguyen, as well as newer members Kirsten Kilponen and Ten Izu, about designing via group chat, fashion as research, and what it means to be “possessed by e-commerce.”

———

OLIVIA KAN-SPERLING: You’ve described what it means to be “vaguely Asian” in every interview and press release and artist’s statement connected to your work at CFGNY, and always in different ways. That mutability strikes me as potentially part of your concept of “vaguely Asian.” So: what does “vaguely Asian” mean to you right now, post-show, in the Japan Society’s auditorium?

TEN IZU: I think I would say the same thing as before, because we’ve been saying it a lot.

DANIEL CHEW: No, no, no. I think if we voice it, it’ll come out differently.

IZU: I think “vaguely Asian” is a sensation. Honestly, it’s so many things. I think it’s this idea that interconnectedness is produced, socially and historically, in moments like these. That temporary constellation is the core—at least in that moment—of what makes a person something, rather than a kernel of abstract identity.

KAN-SPERLING: So when you write that Vaguely Asian is an “affect,” is there a particular affect you’re referring to?

IZU: I think that’s the point, that there is no particular definition.

TIN NGUYEN: That it’s unidentifiable and open-ended.

CHEW: But also, I think you can describe it as a sensibility that you can recognize but not actually name. We all come from very different cultural backgrounds, but growing up there’s certain things that we can all relate to.

NGUYEN: It’s something that you see in each other.

CHEW: And recognize in each other. But then, you’re like, “Well, I can’t actually understand where that comes from.”

IZU: It’s entirely dependent on context.

KAN-SPERLING: Could you be vaguely Asian if you’re not actually Asian? Obviously, you have such great casting for this show, is there anyone who, to your knowledge, is not ethnically Asian?

KIRSTEN KILPONEN: We had two models who aren’t Asian. One was Palmtrees [Olin Caprison] and the other was Micaela Durand. They often get misraced as Asian, so we included them in the show.

CHEW: Vaguely Asian is also sort of about racialization, it’s about living under the label “Asian.” And so someone like Micaela or Palmtrees will get mistaken for being Asian.

IZU: One, because they hang out with a bunch of Asians. But two, they also just look Asian.

CHEW: The rhetoric around identity for the past two years is so much about going back to your cultural heritage or something that is from the past. And we’re like, “No, actually, a lot of what it means to be Asian is to live like Asians do.” And so people who aren’t Asian also experience that. It’s this idea that in the shared alienation of being racialized is where we can build these connections and solidarity.

IZU: There’s also geopolitical cues that come through material or aesthetic sensibility. Former Soviet countries also have that “vaguely Asian” sensibility. There are so many overlaps. Like Daniel said, it’s about this sense of racialization, but racialization comes from so many things like class, migration, colonies, and refugee status—and those things overlap with so many other places because the US has touched most of the world through military force or foreign diplomacy.

KAN-SPERLING: Are there certain stereotypes of “Asian” aesthetics that actually appeal to you? Whether that’s old school orientalist stuff, white women wearing kimonos, or the image of crazy rich Asians running around in head-to-toe Miu Miu.

IZU: One of the more fundamental texts that we refer back to is this Jose Esteban Muñoz essay called Disidentifications. I don’t think that we’re necessarily interested in stereotypes at all, but it’s this act of knowing how you’re perceived, and then producing something generative with it.

CHEW: Obviously, we’re not trying to simply say, “Stereotypes are bad.” There is a type of pleasure that you can sometimes derive from inhabiting a stereotype, playing it up as camp or something, it’s the disidentification thing.

KAN-SPERLING: I have some questions about the collection. I couldn’t really see the text on the clothing. What did that say?

KILPONEN: Here’s some right here on Tin’s shirt.

CHEW: It says, “Your ultimate shopping guide.” And then we have another one that says, “Painter Painter Artist Artist.”

IZU: And the shirt that looks like newspaper print has all these instructions for if you’re burned, I think.

CHEW: Instructions for how to revitalize a body.

IZU: And also dinosaurs.

KAN-SPERLING: So this is all found language?

NGUYEN: Yeah, this is all just language we found at Vietnamese markets.

KAN-SPERLING: I really liked how you described the printed language as forming a pattern that acts as camouflage. Is there a way that your clothing can function as camouflage?

CHEW: I think we always think about clothing that way. The ways in which one is racialized or one reads a person, that visual legibility also works within fashion, so we always see these two as one.

KAN-SPERLING: I also wanted to ask about your process with the tailors you work with—you’ve talked in the past about these interesting mistranslations that occur, where the Vietnamese tailors interpret you as “Western” and therefore make alterations to the garments in order to create more “Western” silhouettes.

NGUYEN: So we still do that with them. And I think the difference or the change that had happened with this collection is that before we were going to Vietnam twice a year pre-pandemic, but then we had a moment where we didn’t. So this last trip I set us up to be able to produce the collection from New York. So now all four of us are making clothes with these tailors through chat rooms and email, and since the three of them don’t speak Vietnamese, we’re using Google Translate to translate our directions into Vietnamese. So this collection embodies language physically in the garments, but also the translated language in its production. And that is something that’s newer to this collection.

CHEW: And even though we’re not speaking properly and they’re not speaking properly, we’re still able to express and create together, which is what we’re all about.

KAN-SPERLING: Were there any mistranslations of form that ended up manifesting in the garment in this collection?

CHEW: Oh my god. Always.

KILPONEN: Always, yeah. But which ones this time?

NGUYEN: Well, for instance, Palmtrees is wearing this jacket here, and the neck is so large. It’s an XL, but the tailors don’t have a sense of what Americans look like. So then I asked Avena [Gallagher, who styled the collection], I was like, “Should we ship it back and get a new one made?” But she was like, “No, it would cost so much to do that. Let’s work with them.” So yeah, there is often this mistranslation in production because of bodies.

CHEW: Not even bodies, but in differing conceptions of bodies.

KILPONEN: They have no idea what an extra large is.

CHEW: They think if the shoulders are this big, the neck becomes that big as well.

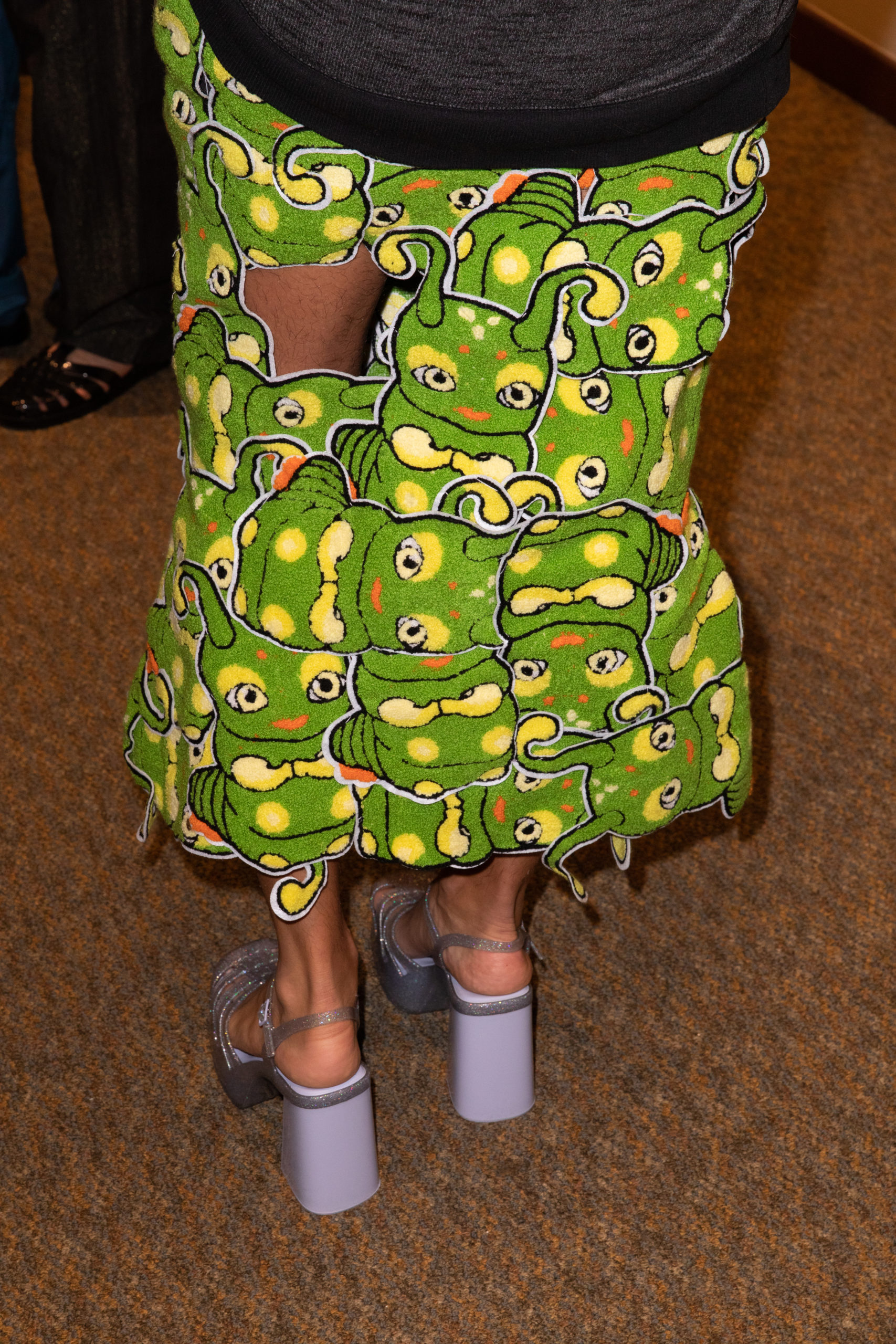

IZU: The skirt that Dakota wore that’s made of patches also had American-style hips in them, but they manifested as these weird kind of teacup handles that a body does not fit into.

CHEW: And it’s also because we don’t come from fashion. We consider ourselves artists who make garments. I don’t think we necessarily consider ourselves a fashion label. So engaging with a tailor who actually does have that expertise is really good. Like, will the garment fit? You never know. But we also like that aspect of it.

KAN-SPERLING: Flows of materials and people are so strikingly embodied and performed in the collection and its presentation: the way the models circulate around the space; the idea of migration patterns, which you investigate—not to mention the art of your production process itself. I imagine you’ve learned a lot about global supply chains since you’ve started CFGNY. Did you learn anything new or surprising with this collection?

CHEW: Yes. What’s interesting is that, because Vietnam has been set up to have this globalized garment production infrastructure where they’re producing clothes for other countries, a lot of young kids in Vietnam are actually utilizing the same infrastructures to make their own collections. And so there’s actually a really big movement of young Vietnamese designers making their own clothes using this infrastructure that global capitalism has put into their country. And they’re diverting certain flows of capitalism for their voice.

NGUYEN: Yeah, there’s a real streetwear scene. And now we’re hiring a lot of those young kids to work for us. They have a sense of what CFGNY is because of the internet, so there is this kind of exchange between us and them.

KAN-SPERLING: Do you feel like those kids have a distinct aesthetic?

NGUYEN: I mean, there’s a lot of brands and they’re all different, but I think the clothes there, for the younger brands, are a little bit futuristic. It’s hot there, but they’re making winter clothes. And they wear it because they’re always in air conditioning, and because the clothes are for photography.

CHEW: They obviously are influenced by Instagram and Western labels, but they are also very connected to the K-pop scene. They’re dressing a lot of K-pop stars.

KAN-SPERLING: Wow. I also wanted to ask about Sigrid Lauren’s runway choreography which, as you wrote in the show notes, is inspired by viral videos of Taobao models.

CHEW: We’ll show it to you right now. They’re videos of models posing for e-commerce photos for Taobao, a Chinese e-commerce site. It’s like a beautiful dance, basically. They do like, 50 poses in 30 seconds, and so the photographers are just snapping pictures while they cycle through these movements. It’s for these Taobao online shops where they do 100 outfits in one day, so they have to be really, really fast and really precise.

NGUYEN: So part of the choreography for this show was this idea of being possessed by e-commerce.

KAN-SPERLING: It’s so inspired. The movement was so bizarre to watch.

CHEW: I know! Like, “What is going on? Does this look good? Is it legible?”

IZU: And it relates to the way that communication happens with the internet now, and this collapse of space and time as well as material.

KAN-SPERLING: And then the movement taking place in this environment that is so classically old-school Japanese…

CHEW: Totally. We like that we’re also opening up Japan Society.

KILPONEN: Yeah. How long has the Japan Society been around?

CHEW: Since 1907.

KILPONEN: And it was the first architecture of its kind in New York.

IZU: I think the exhibition really fleshes out what we’re about, too. Because we are designers, but we are also artists, and fashion is just one medium that we engage as artists.

KAN-SPERLING: Is there a distinction for you between fashion and art?

NGUYEN: We describe ourselves as four artists who research fashion.

CHEW: We’re way more interested in the discourse around fashion and the meta-engagement with all the processes that we use to make a collection.

NGUYEN: I think that because we operate in two different industries—art and fashion—we utilize each one very consciously. So when we do a fashion runway performance as opposed to an exhibition, we’re making an intentional choice that takes into account their respective qualities as different forms of media.

KILPONEN: A lot of the models we choose are artists as well.

NGUYEN: Right, I think that that’s a big part of it: having a runway or a fashion show is about building community. A fashion show does that in a way that an exhibition can’t.

KAN-SPERLING: Totally. And clothing does that too.

NGUYEN: Exactly. People just wear clothing.

KAN-SPERLING: Tell me about the title of the show.

CHEW: Fashion Max 2. [Laughs]

IZU: It’s for fun.

NGUYEN: Our last few shows were called New Fashion, which was taken from these rolls of off-brand fashion labels that just say New Fashion. We would use these generic leather tags on a shirt to spell out “CFGNY”—Daniel’s wearing one of them right now. So Fashion Max 2 is a play on the language in the Vietnamese fashion industry.

KAN-SPERLING: What is your collaborative process?

NGUYEN: We all lead different aspects of the project, and then we teach each other, and then others become experts in it. And then the production sort of evolves.

IZU: But it is very collaborative. We have a sense of how each of us will think about it, so that’s the first thing, but then we always check to see how things have worked.

NGUYEN: We often vote. It’s a democracy.

———

Photographed by: Nick Sethi

Makeup: Shiseido Americas

Shoes: Melissa

Styling: Avena Gallagher

Hair: Chika Nishiyama

Eyewear: Mykita

Choreography: Sigrid Lauren