PARIS — In an age of fashion-tainment, what is the purpose of haute couture? With its grand gestures and links to the red carpet, couture can certainly drive “content creation” with its visually arresting output. This was clear at the couture week that closed in Paris on Thursday. But just as apparent was couture’s role in fashioning the everyday wardrobe of the happy few. The outlandish and the quotidian.

For some, delivering a punch is what matters. See Schiaparelli’s hyperrealist, circus-worthy beasts. On the other hand, there were Dior’s gracious robes and Chanel’s jeune fille tailleurs: nice clothes meant to be actually worn by clients. Somewhere in the middle were Giambattista Valli’s colourful sense of escapism and Armani Privé’s dusty Venetian ball of sorts, a step backwards after seasons of sparkling purity.

The week opened with a bang when Daniel Roseberry’s beasts, culled from Dante’s Inferno and turned into humongous protrusions on costumey dresses, hit the Schiaparelli runway — and sparked immediate outrage online, where critics said the gesture was not only tacky but glamorised big game hunting. The specific logic of using animal heads aside, Roseberry has remade Schiaparelli in tune with the times: his work is baroque, even overloaded, conceived to be seen rather than worn. It’s also designed to attract attention — today’s real currency — and spark conversation, making it much more relevant to the world of showbiz. But for being so of the moment, it’s rooted in creations that appear to be from a past century.

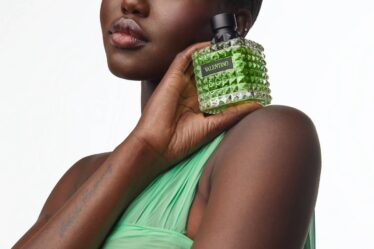

Bold visuals were on display at Valentino, too, where Pierpaolo Piccioli continues to attune the maison to today’s sets of values, “inclusivity” more than anything, whatever this concept means in the exclusive world of haute couture. This season, the designer created a high-octane, ‘80s-inflected collision between couture and the club, between Roman grandeur with its ruffles and bows, on the one hand, and the daring looks and garish colours favoured by hedonistic club goers — think Taboo or Liquid Sky. In its sense of self-affirmation, the show was a kind of political statement. It was also a shock, subverting the very idea of grace which Piccioli has fine-tuned during his tenure at Valentino and replacing it with a harder expression. The outing wasn’t easy to digest, but the search for new forms of beauty is rarely smooth sailing.

Viktor & Rolf proved themselves once again to be masters of humorous provocation and technical wizardry in a tour de force sure to spawn an infinity of memes: an absurdist take on the traditional ball gown that looked like a head-on collision between the bodies of the models and the silhouettes of the dresses.

Robert Wun’s debut was a technical masterpiece full of dry humour. Working with themes of fear and failure, the Hong Kong-born, London-based designer came across as imaginative with a deranged yet rigorous approach. For the moment, his output is confined to occasion dressing and the red carpet but it has lots of potential.

Elsewhere, things tended towards the bland. Virginie Viard’s Chanel is, at this point, clear: rather than delivering a statement, she keeps playing with the classics, reinterpreting them in ways that suit multiple generations of clients. It’s a pragmatic approach, devoid of frisson, but one that keeps the business charging ahead. Viard’s latest outing was light and svelte, all short hems and transparencies.

Dior’s Maria Grazia Chiuri keeps delivering clothes that make women beautiful. The narrative subtext is the same, season after season: feminine empowerment. This season, her inspiration came from Josephine Baker, which made for a collection that swung between dressing gowns and lingerie, impeccable suits and graceful little dresses, offering little surprise but a bevy of immaculately made garments.

At Fendi, Kim Jones was feeling light, too, exploring draping, tieing, knotting; playing with the done and undone. In a glaringly white space, the vision came across as both classic and futuristic. The draping looked a tad rigid, but overall it worked.

At Jean Paul Gaultier, it was Haider Ackermann’s turn to give his interpretation of the JPG codes, a gloomy, murky author, as far from Gaultier’s humour and sneers as it gets. In the clash, Haider came to the fore with very few signs of Gaultier: the bra cups, mainly; the sensual androgyny of tuxedos, too. All of this was filtered through Ackermann’s chromatic sensibility, with pure, sometimes stiff shapes, perfect like a Balenciaga or a Ferré, transfigured by colour, by the angular contrasts of the linings. It was as sublime as it was anachronistic, but haute couture ultimately is.

The emotional high of the week was Olivier Saillard’s latest iteration of the Moda Povera template. Turning his late mother’s very humble and daily wardrobe into elongated silhouettes through couture technique, Saillard offered a glimpse of what subtlety and creation can be. His petit rien, a pair of gloves made with hankerchiefs, will never go viral, but it delivered the kind of profundity the world so desperately needs amidst the silliness of endless theatrics threatening to go viral.