One of the fastest growing areas in the quest for next generation materials is vegan leather. Although these alternative leathers – whether they are plastic or plant-based or both – are marketed as a sustainable alternative to real leather, the jury is still out on their long-term impacts.

Since (spoiler alert) most of them contain a type of plastic called polyurethane (PU), there are legitimate concerns about harmful microfibre shedding, their durability in shoes, and whether they’ll sit in landfills for decades post-use. Not to mention that so long as meat consumption outstrips demand for leather, animal hides are going to waste.

Angela Winkle, the chief sustainability officer at boot maker R.M. Williams – which is exploring vegan leather alternatives through an investment in startup Natural Fiber Welding – says: “We need to know whether leather alternatives can actually improve over time, in the way that leather does.”

“If companies have to make more products and consumers have to buy more products because the materials don’t last as long, then the benefit of lower initial footprints will be completely lost.”

Alden Wicker, the editor-in-chief of EcoCult and author of the upcoming book To Dye For: How Toxic Fashion is Making Us Sick, says unfortunately “a lot of [alternative] leather on the market has a synthetic finish, which can crack and peel”.

Wicker also sees a lot of spin in the space: “It’s incredible the lengths vegan brands go to in order not to reveal that their product is in fact [plastic].”

Jamie Nelson, of footwear label Nelson Made, launched a capsule of plant-based leather shoes last year. “Oftentimes when I got the materials to the factory for the first time, the factory was like ‘there’s a level of PU in here’,” she says. “So, it was the factory who told me, not the supplier.”

To help you decipher marketing from fact, here is a rundown of the most common vegan leathers available.

Plastic leather

Polyurethane (PU) and Polyvinyl chloride (PVC)

The first vegan leathers on the market were made from variations of two types of plastic: PU and PVC . Interchangeably described as leatherette, pleather and vinyl, both PVC and PU are derived from fossil fuels. While they don’t rely on animal products, their impact on the environment should give animal lovers pause.

The production of leather made from PVC releases toxic chemical compounds into the environment, it cannot be recycled and will take hundreds of years to biodegrade in landfill. PU shares these characteristics with PVC, but is generally considered safer for humans. Wicker says: “Polyurethane is preferable to PVC, just from a toxicity level. But it’s still plastic.”

Plant and PU-hybrids

In an attempt to reduce man-made leather’s reliance on fossil fuels, more than one vegan leather pioneer has turned to plants and fungi. While their preferred food waste differs – as does how it is extracted – the end product is a similar plant-PU hybrid.

Generally, the plant matter is processed into a substance that is applied to a textile and coated with PU, for water resistance and durability, making these products a kind of vegan-textile-plastic sandwich. Some use bioplastics – plastics derived from renewable resources, rather than fossil fuels – but bioplastics are still plastic.

The levels of synthetics in these products varies considerably based on whether the textile backing is natural or polyester and on the overall quantity of PU used, but it can sometimes be higher than 50%.

The presence of PU and the complicated blend of materials means these materials will not biodegrade quickly, although rates vary. They are also difficult to recycle.

Mushroom leather: Bolt Threads Mylo

Used by Adidas, Stella McCartney and Ganni, Mylo is one of the two mushroom leathers on the market. The mycelium (the roots of fungi) used to make this leather alternative are grown in vertical farms powered by renewable energy using agricultural waste. The mycelium grow into a foam-like substance that is harvested and processed into sheets of soft material.

This is tanned to give it the appearance of leather, and finished with a thin water-based PU coating. Wicker says, while there is “a ton of hype” around Mylo, “in the end it falls in the category of plant-PU blends. So, better than pure polyurethane, but no more interesting than other plant-PU blends.”

Mylo was one of the leather alternatives Nelson included in her capsule. “I’ve got to say I was a little bit disappointed when I first found out about the PU components,” she says. But the PU is necessary to give the material the properties required for footwear, like flexibility, strength, and water resistance. “So, for me, I guess the benefits outweigh the negatives.”

Pineapple leather: Ananas Anam’s Pinatex

Used by smaller labels, including Twoobs and Bohema, Pinatex is made from the fibre of the leaves of pineapple plants grown on farms in the Philippines, Bangladesh and the Ivory Coast. It takes 480 pineapple leaves to make one square metre of Pinatex, which seems like an awful lot of leaves, but since they would otherwise be considered waste, this is a good thing.

To make Pinatex, the pineapple leaves are mechanically processed to extract long fibres that are then dried in the sun or an oven. The fibres are purified using a corn-based polylactic acid, a kind of bioplastic. This is turned into a mesh that is coated in pigments and water-based PU resins.

“It’s a great story that it’s upcycling and making use of agricultural waste in a socially beneficial way,” says Wicker. “It’s too bad it still has synthetic ingredients.”

Nelson considered using Pintex in her capsule but found the appearance “just too rustic”. Aesthetics are a challenge when working with plant-based leathers. When researching materials, Nelson has to ask: “Is it going to work with the types of shoes that we create?”

Cactus leather: Desserto

Used by H&M and Everlane, this leather alternative is made with nopal (prickly pear) cactus leaves that are grown without chemicals or irrigation on a ranch in Mexico. The leather is made by combining milled cactus leaves with protein and a non-toxic liquid polymer.

after newsletter promotion

Desserto do not disclose what the liquid polymer is, citing intellectual property concerns, but describe it as a biopolymer. However, a report released by the FILK Freiberg Institute in 2021 investigating the presence of chemicals and plastics in a range of leather alternatives suggested Desserto suggested does contain PU, and found five restricted chemical substances in the sample tested.

In response to the report, Adrián López Velarde, the co-founder of Desserto, told Eco-Cult that they do not intentionally use the chemicals found by the FILK report, and that their presence could be due to cross contamination. “The cacti element should reduce [Desserto’s] impact, but not more than other plant-PU blends,” says Wicker.

Desserto’s products are used for handbags, footwear and even in cars, and the plant-based content varies depending on what the material will be used for, from 90% to just 30%.

Grape leather: Vegea

Vegea or grape leather is made using the residue of grape skins and seeds left over from wine making, and has been used by brands including Stella McCartney and Pangaia. The residue is combined with vegetable oil and a water-based PU. This mixture is then used to coat a cotton backing, then a waterproof coating is applied.

Wicker says the same process is used for Appleskin, a type of – you guessed it – apple leather.

Vegea and Appleskin’s products both vary considerably in the amount of synthetic materials they contain.

Mushroom leather (again): Mycoworks’ Reishi

Reishi by Mycoworks is another mushroom leather. It is made by growing mycelium directly on cotton or other fabric backings, then finishing it with either a petroleum or plant-based coating. According to a peer-reviewed life cycle assessment that was published late last year, Reishi has less than 1% polymer (plastic) content, the lowest of the plant-PU hybrids.

The LCA suggests Reishi’s carbon footprint is 2.76kg per meter squared – just 8% of real leather’s average footprint, less than most alternative leathers, and on par with Pinatex. It also has a luxurious feel that is close to the real thing.

The drawback is the price. Wicker says: “Its manufacturing process is so fussy that right now it’s an ultra-luxury product that only the most rarefied brand could afford.” Case in point: the fabric’s highest profile adopter is Hermes.

Plastic free

Cork or natural tree rubber: Natural Fiber Welding’s Mirum

Used by Camper, Stella McCartney and Bellroy, Mirum from startup Natural Fiber Welding is entirely plastic free and 100% plant-based. There are several versions of Mirum, whether for shoes or accessories, and they rely on different ingredients, including natural tree rubber, rice, cork and coconut waste.

Mirum is so variable its colour, shine, texture, thickness, grain and even its scent can be customized. It also has a patented substance – used to give the material durability – which is entirely plant based and sourced from renewable feedstocks.

Natural Fiber Welding says the material can be recycled back into new Mirum, making it 100% circular if the product it is used in can be disassembled and returned to the correct facilities – but the logistics of how this can occur depend on the brands that use the material in their products.

“This material is quite honestly my favourite that’s on the market – for now, anyway,” says Wicker. “Biodegradable, recyclable, completely synthetic-free, and the startup … is very transparent. I’m not sure it rises to the performance and look of real leather, but I could be proven wrong.”

Prawn leather: TômTex

TômTex isn’t technically vegan, because it’s made from a biopolymer called chitosan, which comes from shrimp shells and mushroom waste. Like some leathers, it is a byproduct of the food industry and is both readily available and very cheap – which means unlike some alternative leathers, where supply and cost are an issue, TômTex has enormous potential for scale.

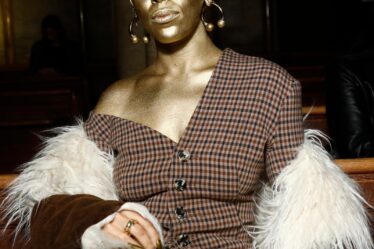

Although relatively new, TômTex was piloted by designer Peter Do to create trousers and tops shown at New York fashion week last year and the brand’s founder says the product will be available at a commercial scale by the end of 2023.

To make TômTex, raw chitosan is melted down into a viscous brown liquid that is poured into moulds. This makes it one of only two plastic-free leather alternatives.

“It will be at least a year before we know if this young startup lives up to its promises, but so far I am very excited about this material,” says Wicker. “It’s 100% bio-based, biodegradable, non-toxic to the point of being edible, made from waste, performs as well as leather, and promises to be affordable.”

Wicker says she has seen a two-year-old TômTex wallet, owned by the brand’s founder, Uyen Tran. “It still looks amazing.”