Jack Davison recalls a conversation with his mother years ago when he was being negative about something, which was unusual enough in itself that she pulled him up short. “The thing that was really exciting about you as a child was that you were always full of awe at everything. Don’t stop being excited by stuff.” He bowed to maternal wisdom.

Growing up in a small village in Essex, northeast of London, Davison was always rapt in nature, always easily excited by everything around him. He wanted to be Jacques Cousteau when he grew up. “I’m very close with my sisters and we spent a lot of time just playing in the garden. Dad’s a builder, and he and Mum were very good at telling us to go and make a teepee, or create something.” And then Jack would want to photograph it or draw it.

Nothing’s changed in the decades since. Davison is the kind of sunny soul whose enthusiasm is contagious. He took on a personal trainer last year in readiness for Selma, he and wife Aggie’s second child. “Basically, I want to be strong because carrying children is a back killer.” Now, broad of chest, rosy of cheek, Davison is the very vision of a robust country boy. Unsurprisingly, he likes getting his hands dirty. He rhapsodises about the six months he spent working as a labourer, not really taking any pictures. Best time ever. Now he’s in the process of turning his backyard into a working garden. There’s even a large frog pond, waiting for the frogs to take.

Small wonder his mother was taken aback by that flicker of negativity. Davison insists he is untroubled by self-doubt, nor is there any darkness in his nature. It lives in his work though. He has become famous for his portraiture. Its signature is often an intense chiaroscuro, with shadows so deep they swallow light. The first time I saw his pictures, I was staggered. Who on earth was this person? What time? What place?

Davison is happy he has that effect. “It just gives you so much more freedom. I always loved the idea that someone finds a sheaf of photographs of mine without any labels. I could be long dead. Maybe there’s no record. I mean, it’s probably easier with technology now, but the fact that you could have thought, ‘Oh actually, I don’t know when this is from or who this was…’ Even when I was on Flickr, people used to think I was some 50-year-old Spanish or Russian photographer.” (For the record, he just turned 32.)

Davison is self-taught. He was a Flickr baby. “I started when I was 13 or 14, posting online. And I found really quickly what I was drawn to, maybe through some of the art I’d seen as a kid… the 1920s, the early Modernists, the Surrealists… and then the photographers.” The only photography book he remembers in the family home was Bert Stern’s last sitting with Marilyn Monroe — “and I only looked at that because I was a horny teen and there were boobs.” So Flickr was invaluable because it was an education. “Just images, presented in white space. It wasn’t conflated with the idea of the self and the present.”

Through Flickr, he discovered kindred spirits, none more important than photographer Brett Walker. “I found people who he knew, who he taught, and we all had this similar love of things that felt out of time and weird. What united a lot of us was not necessarily wanting to take photographs that felt like they were happening now.” Walker was a name in the 1980s and 90s, when magazines like i-D and The Face created new venues for deeply personal, experimental work. Dark, troubled, he was everything Davison wasn’t.

He considers Walker his mentor. “When I started studying with Brett, his work definitely shaped me. The close cropping, the love of the street. Brett would always say, ‘Crop everything out of your photo until it’s clear.’ It was always about making singular images, which is not necessarily taught that often. I didn’t do a university course but I know a lot of the time the kids I mentor who are at university are always told to plan a body of work. It has to have an intense meaning behind it. What I’m trying to do is get people to just take pictures, and then think about it after.”

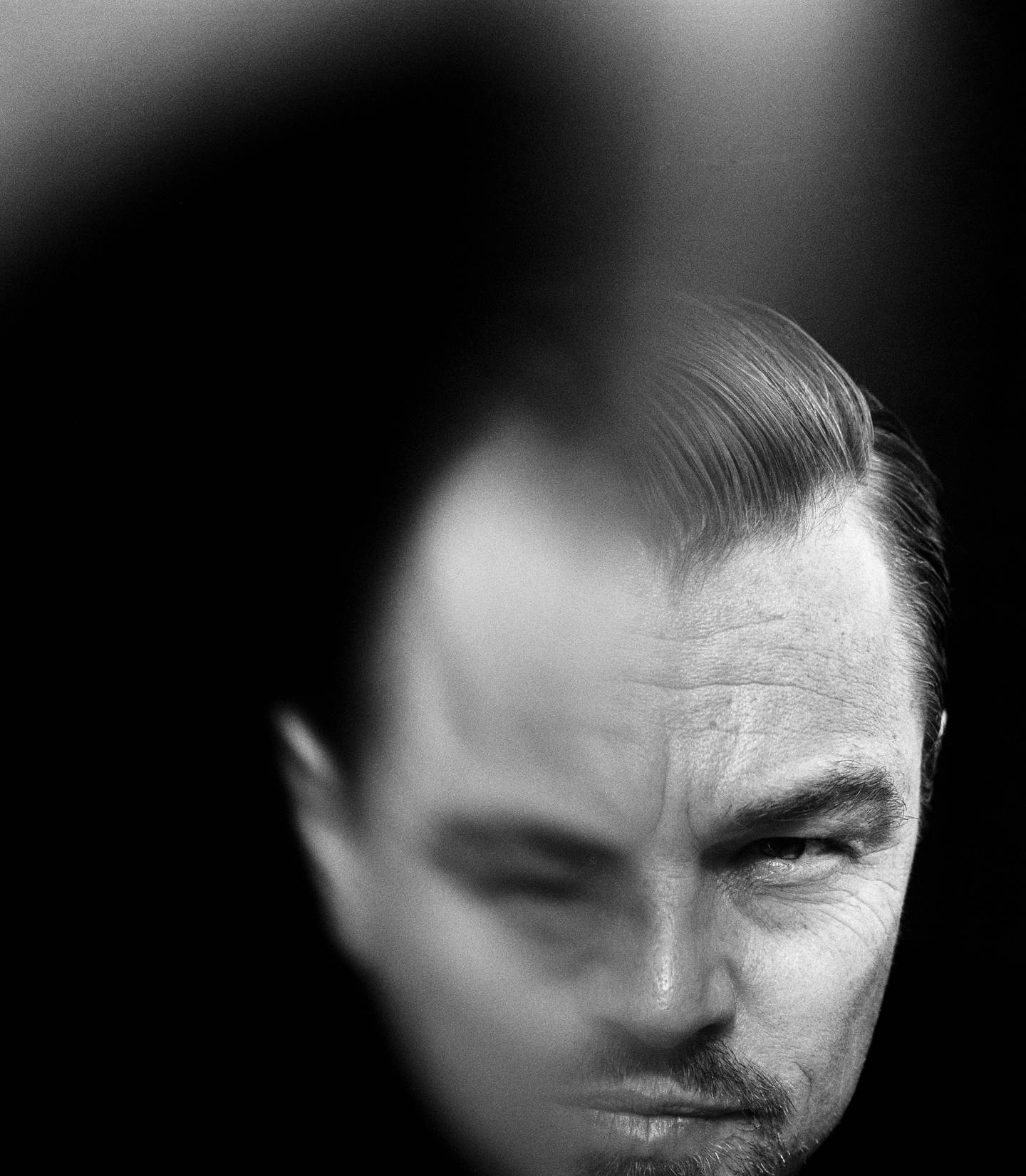

“Lots of photographers want their photographs to be timeless,” wrote Kathy Ryan, the legendary Director of Photography for The New York Times Magazine, in the catalogue for Davison’s show at the Cob Gallery in London last October. “Jack wants literally to remove time from his work. His work features no fashions, logos, cars or other signifiers that will anchor the photo forever to its time.” Ryan makes careers and Davison’s professional breakthrough probably came when she selected him to photograph the annual Great Performers portfolio for The New York Times Magazine in 2016. Its title, L.A. Noir, nailed his interplay of light and shadow.

He likes hard, bright sunlight for his shoots, precisely the light that originally made Hollywood the hub of the movie industry. That might explain why his work is often described as cinematic. Or that it occasionally echoes early movies in its chiaroscuro intensity. It took a while. He was a year into his career before he realised that he got good stuff when it was sunny. “It’s funny, at first I thought that everyone loved really hard sunlight then I realised people prefer the golden hour, the softer light. But I like that there’s just no hiding. It can be very stark, throw way more shadows into the space or begin to add abstraction.”

So that first “Great Performers” portfolio was a perfect storm for him. “It combined so many things I like. The classical styling of 1950s noir, the hard light… I wasn’t allowed a studio, so I was outside in a parking lot, and there was none of the faff which I don’t like in studios there. And then I was just left to my own devices. People would get ready inside and they’d walk out into this parking lot and be a bit confused, which was great because they were kind of off their stride. And then we’d make pictures together.” One consummate Jack moment: Emma Stone, batting away a perfectly surreal shower of fedoras. She’s never looked better.

In 2019, Ryan commissioned Davison for a second “Great Performers” portfolio. “The original pitch was they wanted to essentially do nudes of famous people, or very revealing photographs. But they didn’t do any of the legwork with the people beforehand. So that kind of came down to me. Brian Malloy was doing the styling at the time and we had to have these conversations on set, and I ended up saying, ‘Look, I’m not going to sit down with Robert De Niro and be, like, pants off! There’s no way in hell you’re gonna get anyone to sign off on this.’ JLo didn’t wear much but that was kind of her M.O.”

Both portfolios are easy to find online. They make an ideal introduction to the portraiture that has established Davison as a natural heir to the grand masters Richard Avedon and Irving Penn. That’s because it’s even easier to appreciate the subversive, entrancing impact of his work when you’re looking at pictures of people whose faces you’re familiar with from a hundred other photo shoots. Suddenly, they’re less familiar.

“When I was coming up, I looked at those Avedon and Penn pictures where there’s a real rawness,” says Davison. “They’re getting to someone and there’s a real emotion to it. And I was wondering why no one was using this opportunity, to do something radical or make something weird, and push these people.” He brings up the famous Avedon portrait of the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, where, just before the photographer pushed the button, he told the pug-crazed duo his taxi had run over a small dog en route to the shoot. Or so the story goes. Their unhappy faces in that picture came to define how the rest of the world imagined they must feel about their blighted lives. “That’s not the space I want to put people into,” Davison clarifies quickly. “It’s just that I go, ‘Why wouldn’t we make something weird and expressive, and try to do something that isn’t just gonna be another picture of you?’”

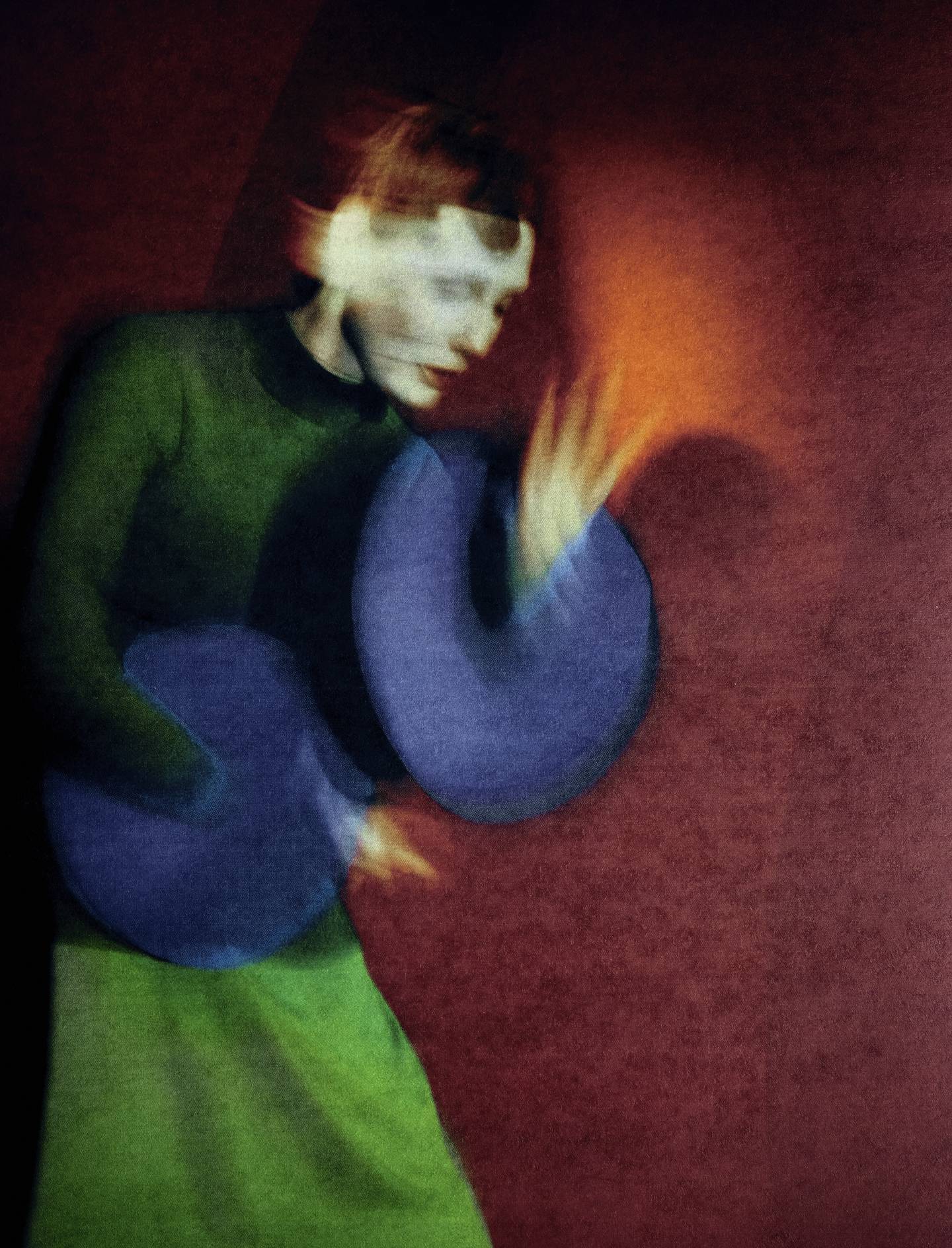

His recent sitting with Cate Blanchett, again for The New York Times, is a golden example. “I’d already photographed her for Vogue and we got on really well, but it was kind of a missed opportunity because she was playing herself and it felt a bit celebrity-portrait-y. But I figured Cate was probably a bit like Tilda, who will just go for something if you say, ‘I’ve got this really good idea.’ So I did lots of mood boarding and I told her, ‘I think we should turn you into this weird Bauhaus puppet.’ And she was, like, ‘Yeah!’ But when she turned up, I was still a bit ‘Are you gonna go for it?’ And then obviously, she was just amazing.” When I mention that Blanchett is almost unrecognisable as “a weird Bauhaus puppet,” Davison is pleased. “Good, that’s what I wanted. Actually, I got in trouble for that with W Magazine because I did a shoot with Zendaya and they were, like, ‘She’s not recognisable enough’. And I said, ‘She’s Zendaya, she’s one of the most famous people in the world.’ She actually messaged me. The picture she loved most was the one I got in trouble for because you can’t see her. She wanted a print. She said, ‘It doesn’t feel like me, and I like it.’”

So Zendaya was happy, but I have to ask, “What did Cate say afterwards?”

“That’s always the sad thing, I didn’t hear from her afterwards.” In fact, he rarely hears from anyone. “It’s probably just ego. You’re expecting someone to be like, ‘Oh, I love this photo!’ I don’t know, you just hope that someone is either rattled by it because they’ve never seen themselves like that, or hopefully they just feel like there was something that was worth their day.”

I get the feeling that Davison has a somewhat ambiguous attitude towards photographing the famous. “It’s kind of fun,” he concedes, “if you have that revulsion and attraction of being intrigued by those people. With “Great Performers” and jobs like that, you have to sign in and you don’t have the list but you know there’s gonna be good people on it. But when people ask me to photograph a particular person, my rule generally is: if they were just someone in the street, would I cross the road and ask them to sit for me? I do that, if there’s someone who really grasps me. I nearly did it today actually. I was walking up to Olive’s nursery, it was raining and there was this lady in a headscarf, running late. And I was basically too shy at that point. My aim this year is to do more of that. I used to do it a lot when I was a teenager. I was a bit more spontaneous. But having a baby with me, I now feel it’s less of a threatening thing. So I’m, like, ‘Look, I’ve got a child.’” And, as of February, there are two kidlings to soften the Davison approach.

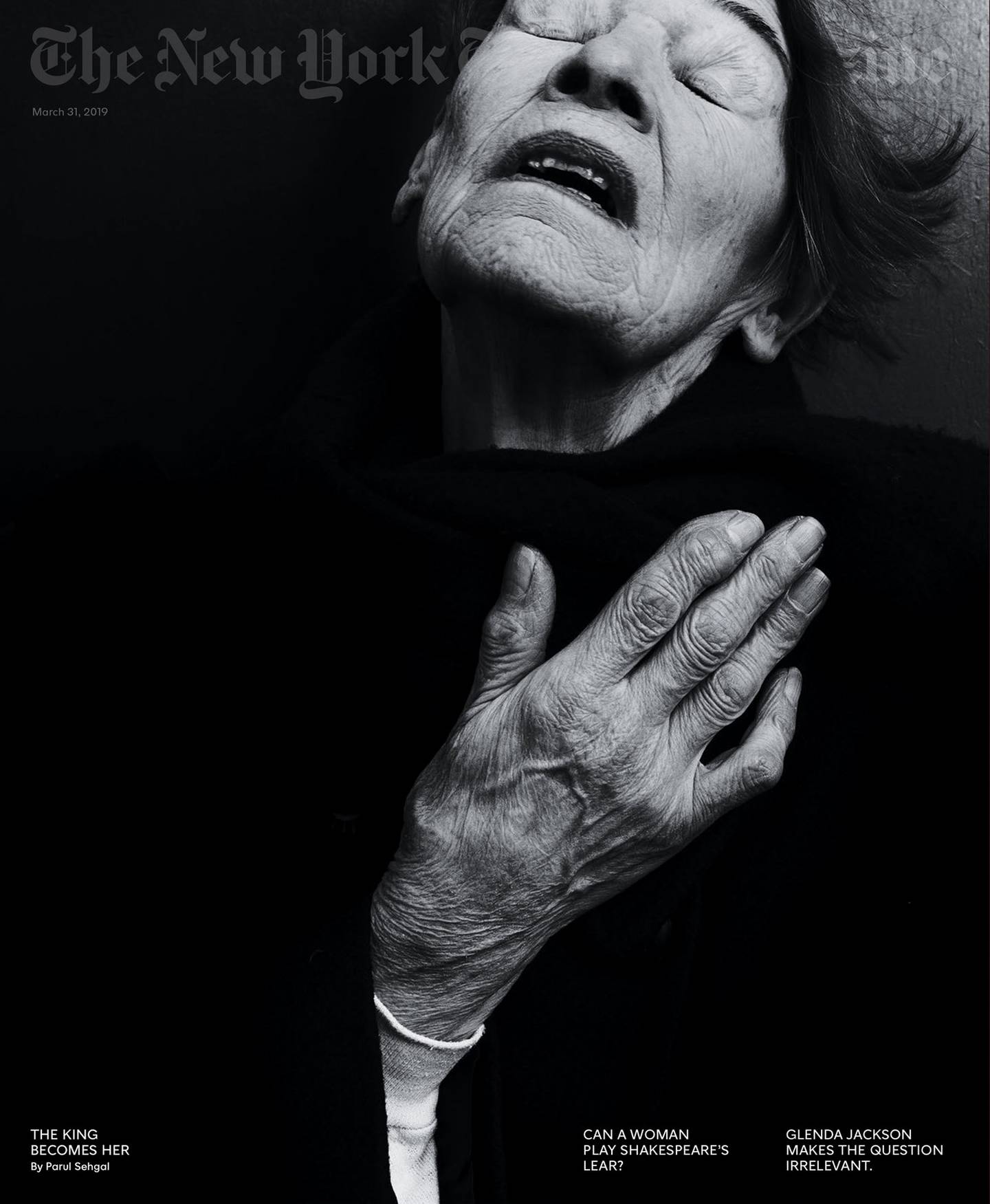

He does keep a list of people he’d like to photograph. “RuPaul I would love to do. I’d really like to shoot him out of drag. But then there are your Ian McKellens, your classic actorly old faces. He’s someone I’ve actually pursued for five years and got nowhere with.” He’s done well with those faces in the past. His favourite-ever cover for The New York Times Magazine is Glenda Jackson.

He photographed her in his living room, where we’re currently sitting. It’s a favourite location too, because of the way the sunlight moves so fast across the wall. “It’s often the thing that I don’t plan, maybe a bus goes past and hits a bit of light that I didn’t see, or the sitter drops something, or they sneeze. So the picture of Glenda that The New York Times ended up using on the cover, she was going to wipe her nose essentially, and it was just this moment. That’s not what you see it as.” True enough. You see straining hands, eyes sealed shut in utter anguish. An entire emotional meltdown, in fact. It’s that thing Davison was talking about earlier. “I have that disconnect where I don’t feel I’m a particularly intense person. And I don’t have those demons that people expect me to have. They expect me to be quite dark and brooding. And I’m not. So I don’t know how that gets to here. But I do know that I want photos to be emotional and emotive. That’s why I struggle with a lot of portrait photography.”

He says it’s the same with one of his “classic” images, the lunging dog. It was his mum’s Labrador, reaching for some ham. “But it looks like it’s going to bite your throat out. It’s those moments that you have no control over that are the most exciting for me. And now it’s even funnier because Stephen King put it on the front of Cujo. So I messaged the publisher and told him my mum will think it’s the funniest thing that her stupid Labrador is the face of the most evil dog.”

In a way, the lunging dog embodies the essence Kathy Ryan defined in her catalogue: “The transcendence to be found in the everyday.” There’s another “classic” image which stays with me for the same reason. It’s superficially a picture of the back of a man in a rain-spattered coat at a racecourse in Scotland, deciding on his next bet. For me, and clearly for Davison, it’s a lot more. “It’s just one of those pictures which is distilling something to its most sculptural form. It’s so obviously a man’s back in the rain and the dog picture is so obviously a dog and I’m not actually showing you that much of either. But you’re still getting all of that.” And it’s the essential “that” which makes his images so powerful.

It may be clearest in his personal work, particularly the life’s project he has embarked on with his and Aggie’s families, because that is such a long-term emotional commitment. He imagines publishing it in 20 years. The idea originated from an approach by Double Magazine, which wanted a Christmas story. He immediately thought of his family, which he describes as a big, loving Italianate situation. And then he put his 74-year-old grandmother in front of the camera. “When you slick her hair back, something miraculous happens. She doesn’t necessarily mean to do the poses she’s doing, but it’s just like she’s been a ballerina her whole life. What she looks like normally is so far removed from the pictures I take of her, but the transformative power of shooting her is why I will always come back to portraiture.”

And now it’s an ongoing situation, one which will record the births, the inevitable deaths. That makes me wonder if Jack ever gets sad when he takes a photograph. It is, after all, the record of a moment that can never come again. “I don’t necessarily think about it in that way,” he replies. “Part of it is that at least it’s being documented and there’s a record of it. I’ve got this relationship with my grandmother, there’s a series of really special pictures that we made, and then my wider family becomes part of the project and I’ll be able to show Olive and Selma those pictures of their great grandma and how amazing she was at this point. And that’s just exciting to me. Though I’m sure it will be sad at some point.”

The family photos are an extraordinary synthesis of the various strands of Davison’s work: intimate, fantastical, transformative. It’s enough to make me wonder how he sees himself. Artist? Portraitist? Documentarian? “I always used to call myself a documentary photographer, but I’m not honest enough for that because I do too many surreal-y things. And I feel it’s a bit big-headed to call myself an artist, because I’m a Catholic boy and I can’t be too big-headed. It makes me stressed. So I thought maybe I’m a portrait photographer. But thankfully, the term ‘photographer’ is vague enough that you can be everything.”

“For me, it’s just trying to capture an in-between moment. I think that’s why I shifted away from calling myself ‘documentary’ because it’s more than that for me. It’s like taking what you have in front of you and twisting it or shaping it, so that it’s something that only you could see or you could find. So ‘photographer’ is good. But I don’t know. I still like the fact that you have to ask the question. You don’t necessarily go, ‘Oh, he’s this photographer or he’s that photographer.’ A lot of it is about subverting expectations of what I might do next.”

In his exhibition last year, Davison reproduced some of his best-known images as photographic etchings. The etching process appealed to him as a physical antidote to sitting at his laptop, or drawing. You don’t see it much in photography, but Davison was excited by the texture of etched pictures, especially the blacks you can get into them. “The dark room doesn’t really appeal to me. It’s really hard to find a print process that will take the amount of black that I want in a picture, but there’s something about churning out a print on an old press. With etching, you simply can’t add too much ink, and it really holds it.”

And he liked the randomness of the result. “I did a print course but I’m not a talented printer, so I made mistakes, which makes interesting things. Each print is different.” The effect was obvious in the Davison “classics”: the lunging dog now even more aggressive because of those inky blacks; the huge, hulking man viewed from behind, the drops of rain on his coat now almost three-dimensional in their stark definition. “I’m always chasing texture, it’s something you want to hold and interact with.”

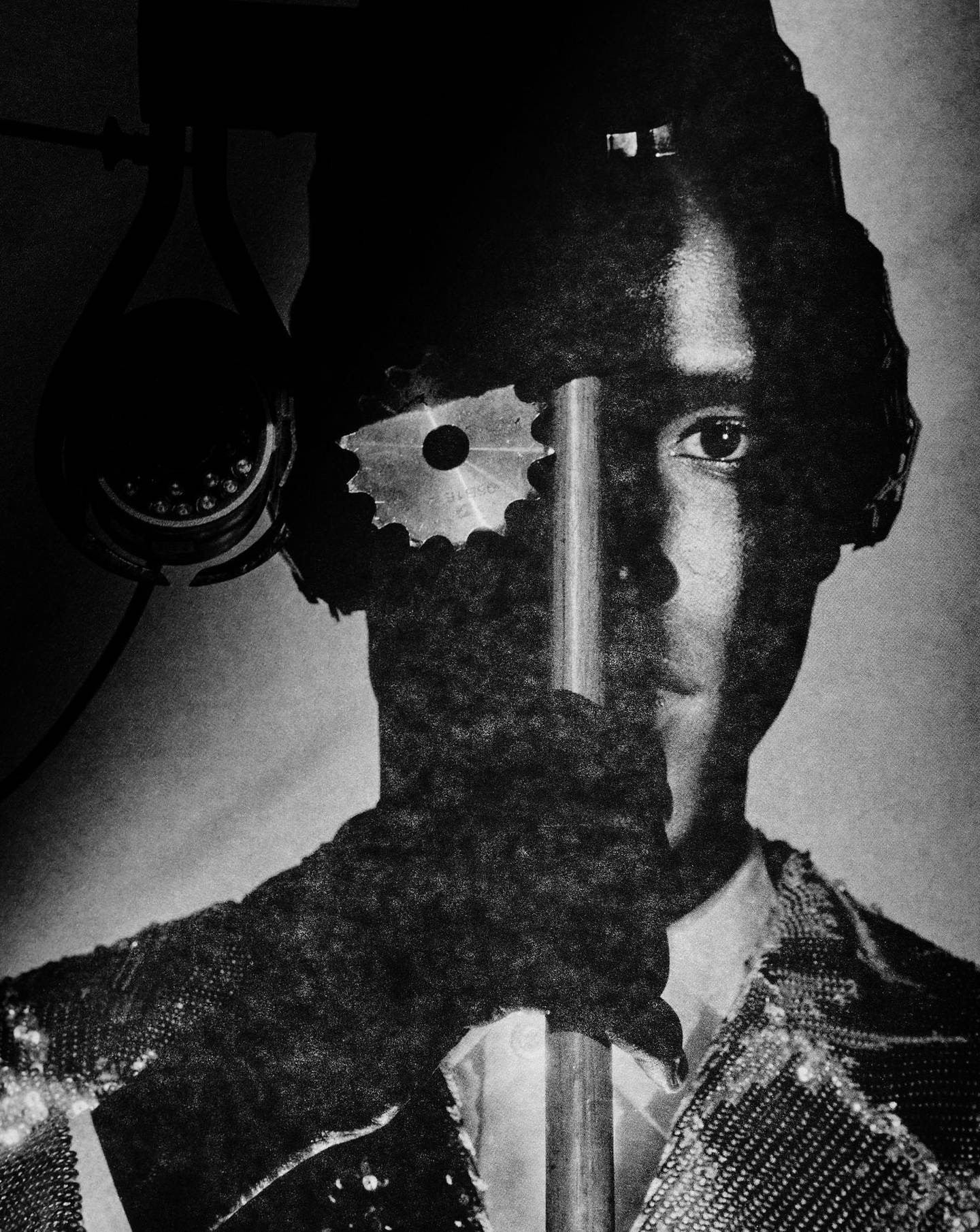

It’s worth a reminder in the midst of all this that Davison has a fashion profile: commissions from brands like Hermès, Burberry and Moncler; collaborations with Craig Green, Marni and Alexander McQueen; editorial for a handful of Vogues and fashion bi-annuals. He likes doing fashion photography. “I think there’s a creative space and you can make it whatever you want, it really lends itself to surreal things. I sometimes really feel like it’s the only space to make certain images. Though I don’t have a love for clothing necessarily, I like what clothing can do and I like structural things. But a lot of my favourite pictures of clothes are just shapes, or they’re black spaces. So what I’ve found is some stylists might be scared that they won’t see any of the work they’ve done, which I completely understand.” One stylist who isn’t scared is Ibrahim Kamara. Davison and he worked together for the first time last year for Luncheon magazine, and again for Dazed, which Kamara edits.

The thought of future collaborations between such protean talents is one of fashion’s more exciting prospects. So, as a closing salvo, I would like to suggest a shoot inspired by Davison’s obsession with Salvador Dali. He acquired it during his childhood visits to the Dali museum in Figueres, Spain, just across the border from his grandmother’s caravan in the South of France. For an imaginative kid, the sight of a giant red castle covered with eggs and croissants was thrillingly nuts. “I was thinking I’ve never actually done a shoot that’s informed by Dali,” Davison muses. What Jack does next? Ib, let it be so.