Jenna Lyons’ didn’t become a sensation because the public just happened to stumble behind the scenes of J.Crew, and discover a designer with (inarguably) great style and a larger-than-life personality. Circa 2007, the question of whether or not to introduce consumers to J.Crew’s then little-known creative director was a subject of debate within the upper tiers of the company.

“We pondered it,” a senior executive told me. “Was it a good idea? Was it a bad idea?”

Today, in the midst of a promising turnaround, J.Crew faces a version of the same questions. One imagines that CEO Libby Wadle, a one-time disciple of Mickey Drexler, the CEO who famously greenlit Project Jenna in the first place, would like to have it both ways: to reap the benefits of publicising her new duo of cooler-than-thou designers — this time around, men’s creative director Brendon Babenzien and Olympia Gayot, the head of women’s and kids’ design — without boosting either of those designers to the point where they overshadow the brand itself.

Back when the “will we or won’t we” question of Jenna was being debated, there was the big picture to wrestle with: Was it wise for a brand that aims to dress a wide swath of America to closely associate itself with one very specific woman — a New York creative with a taste for high fashion? Where would J.Crew be if it aligned itself with Lyons, only for her to lose her magic touch, or depart for a better gig? What if she were to evolve, personally and creatively, in a direction that coloured significantly outside the lines of J.Crew’s quirky-yet-conservative identity? (Ok, nobody saw that last one coming.)

But at the time, the question they spent the most energy debating was: Will anyone even care who designs J.Crew? Consumers had never really noticed who designed their mass brands. Even today, it is hard to say who designs Banana Republic, Gap, or Ann Taylor.

That worry seems almost laughable now. As a public-facing persona, Lyons wildly surpassed what J.Crew had ever hoped to achieve. Her own thick black glasses, her scraped-back hair, her orangey-red lipstick, her mix-and-match magpie style — these became inseperable from the brand itself. Eventually, her star shot so high, J.Crew found itself left in her long shadow.

After the designer stepped down in 2017, a chastened, debt-mired J.Crew was determined never again to put all of its eggs in the basket of a single creative. In early 2019, reporting on a floundering J.Crew for a feature in Vanity Fair, I interviewed a company higher-up who declined to be identified. J.Crew had just hired designer Chris Benz, who with his multicolor hair and debonair-millennial persona seemed intended to fill the Jenna-size hole in J.Crew’s identity.

But when I asked this exec whether Benz would be their “new Jenna,” the answer was unequivocally “no.” We are never doing that again, she told me. Indeed, Benz’s title, chief design officer — as opposed to Lyons’ creative director, then president of the J.Crew brand, then president of the whole J.Crew group — was intended to drive home the point. True to her word, J.Crew never did showcase Benz. But then again, maybe they didn’t have time to: He was out by 2020.

As the company continued to struggle, it began to seem increasingly implausible for J.Crew to simply decide to go back to selling itself without a “face.” Without the focal point that Lyons had for so long provided, it had become hard to see what J.Crew was. Hard to see its clothes as aspirational, worth their slightly higher price tag than its neighbours at the mall. Without the brand’s former fashion halo, what made this pair of chinos or that button-down better than the one you could buy somewhere else — maybe someplace hipper, greener, more in step with the times, or just … cheaper?

Which brings us to Babenzien and Gayot. Today, J.Crew has what it desperately needed: two designers who are arguably a whole lot cooler than the company they work for.

Babenzien, to a degree, has solved the Lyons problem for J.Crew on the menswear side. Given his roots in the skatewear brand Supreme and his own downtown-cool label, Noah, Babenzien walked into J.Crew in 2021 with enough cred to win back a wide swath of fashion fans from the start. Better yet, he has opted out of social media, emphasising in interviews that he’s a little shy in the spotlight. Which, of course, only makes him more revered by press and streetwear kids alike while avoiding the too-big-for-the-brand Jenna problem.

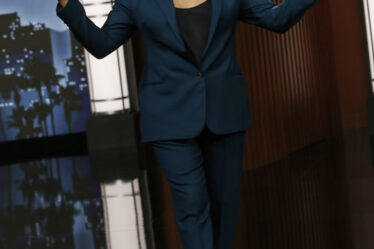

But for Gayot, on the larger women’s side of the business, it’s trickier. J.Crew at first appeared to seed the designer in the press more gradually, perhaps waiting for her designs to arrive in stores. But last year the company pulled off the Band-Aid, encouraging Gayot to make her Instagram account public. Almost immediately, the designer, with her long Botticelli curls and knack for relaxed, nonchalant layering, has become a blue-checked online style star. In hundreds of selfies snapped in the mirror of her corner office, she makes J.Crew clothes (tossed together with a smattering of Prada and Celine) look new, now, and wildly desirable.

On cue, Hollywood insiders now request the name of Gayot’s hairstylist in her IG comments. The website Who What Wear breathlessly documents every piece she wears. Jenna Lyons herself posted on one of the designer’s selfies last year: “I love the way the clothes look on you :-)) You should be the model!!!

Sound familiar?

Where “Jenna’s Picks” was once the most profitable page of the company catalogue, now racks of “Olympia’s Picks” are stationed at the door of some stores. Will Gayot follow in Lyons footsteps up the red carpet of the Met Gala on the first Monday in May this year? It seems all but inevitable.

This after all, is the identity that comes most naturally to J.Crew — America’s most fashion-adjacent mass brand. For that, it needs a fitting representative visibly at its helm.

However, the company may find it easier to regain its fashion mantle than to win back a following that will be even more critical to its survival: the customer. These people are more likely to be the sorta-cool dad who has never shopped (or heard of) Noah; the working mom who wants to feel a little special in what she wears to the office.

Design-wise, Gayot seems to have walked in with an understanding of her customers — perhaps because she worked under Lyons herself: She’s seen J.Crew firing on all cylinders, and she’s seen it fall to pieces.

You can spot the J.Crew DNA in her bright, painterly colour combos (Gayot has a background in art); in her candy-colorued cashmere; in the cable knit of a sweater, its old-school weave thrown off kilter; in the softness of an Easter egg-hued chino. But in the February issue of Harper’s Bazaar, the designer made it clear that she knows J.Crew shoppers will follow her only so far: she may pair slip dresses with cunning little “evening socks” and loafers, but she knows most customers won’t take that risk.

The last time J.Crew scaled fashion’s Mount Olympus, it was that core customer who eventually felt left behind. In order to really be considered “back,” J.Crew has a tricky needle to thread. It must reinstate itself as a fashion darling and please customers who have a love-hate relationship with the “fashion insider.” That’s a dual identity that we don’t expect from Gap, or Banana Republic, or Ann Taylor.

But J.Crew must be both because at one time — and for a briefer span of time than you might think — it really did kill on both levels. Even as Gayot’s Instagram following ticks upward, and a growing pile of glowing profiles in the fashion glossies make it clear that her star is ascendant, it’s too soon to say whether the other half of that mission is yet fulfilled: Are the bulk of the people who really buy J.Crew — people who are stylish but not especially adventurous; people who might not be taking their style tips from social media — back on board?

These folks may not register, or identify with, the hip new talent behind the curtain. But they do crave easy-to-find, current but not quite trendy, better-than-basic clothes, and they’re willing to pay a J.Crew premium (with, ok, 40 percent off) price for them.

Truth be told, in all the years J.Crew was laid low, no other brand quite stepped in to fill that void.

Maggie Bullock is the author of the new book “The Kingdom of Prep: The Inside Story of the Rise and (Near) Fall of J.Crew” and the cofounder of the women’s media newsletter, The Spread, on Substack.

The views expressed in Op-Ed pieces are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Business of Fashion.

How to submit an Op-Ed: The Business of Fashion accepts opinion articles on a wide range of topics. The suggested length is 700-1000 words, but submissions of any length within reason will be considered. All submissions must be original and exclusive to BoF. Submissions may be sent to opinion@businessoffashion.com. Please include ‘Op-Ed’ in the subject line and be sure to substantiate all assertions. Given the volume of submissions we receive, we regret that we are unable to respond in the event that an article is not selected for publication.