On a mild evening in early spring, an unassuming street in Brooklyn momentarily became the destination for New York’s fashion crowd. Club kids, streetwear aficionados and people dressed like Neo from The Matrix vied for a spot in the swelling crowd. The reason? A fashion label called Luar, which has become so hyped in recent years that even those not usually accustomed to queueing will gladly get in line.

It was worth it. Once inside, the show felt like a party, with Tony award-nominated playwright Jeremy O.Harris and rapper A$AP Ferg in attendance, cheers coming from the usually po-faced audience with each model, and classy and clever takes on evening wear and suitable for work suiting on the catwalk. It then – seamlessly – turned into an actual party, the kind with drinks on trays.

Luar’s designer, Raul Lopez, speaking a few weeks after the show, is wide-eyed but smiling when told about the scrum to get in. “It’s become a thing where it’s like getting into a club,” he says, speaking to the Guardian via video call from his grandmother’s house. “The kids start to leak it on TikTok or whatever … and like 700 or 800 people show up.”

Those numbers are testament to how Luar is a name known way beyond those in the rarified world of fashion. This is perhaps partly because Lopez – a queer designer of colour who grew up in a non-gentrified area of New York – stands out from the industry he operates in. Rather than obscure these differences, Luar leans into them and celebrates them – constructing something radical: a luxury label that has appeal beyond the 1%.

If, in the fashion world, New York has long been shorthand for the uptown polish of labels such as Michael Kors and Ralph Lauren, Lopez’s Luar is one of a number of labels finally showing different points of view in this most diverse of cities. Other names include Willy Chavarria, the 56-year-old designer who works for Calvin Klein and is enjoying something of a resurgence of interest, thanks to his genderless designs and diverse street casting. And Head of State, the label founded by Taofeek Abijako when he was 17. His collection in February was a moving tribute to his father’s journey from Nigeria to Spain and finally the US.

Notably, Lopez closed fashion week – a prestigious slot usually reserved for a household name. He sees this as an affirmation. “I was born and raised in New York, [and] coming from these disturbed neighbourhoods … to be able to display my work for the world and for New York, it was an honour,” he says. “In a weird way, it wasn’t really about me, it was about everybody. It’s like ‘I can do this, you can do this too, you know, you just got to hustle.’”

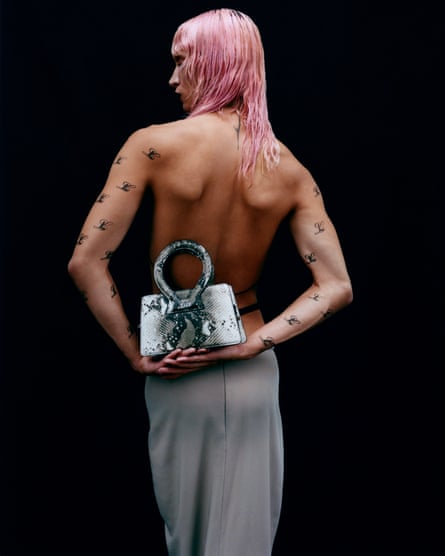

There are other signs of success. He is one of nine finalists up for this year’s prestigious LVMH prize for young designers, with the winner announced in June. He was also awarded the CDFA accessories designer of the year in 2022. And sales are growing – with the Ana bag key to this meteoric rise. The first drop, in October 2021, sold out within 30 minutes, and according to Vogue Business, sales for the brand increased 140% from spring/summer 2022 to spring/summer 2023.

Launched in 2021, the classic square shape with a looped round handle has become a favourite of celebrities including Dua Lipa, Troye Sivan and (delightfully) Patti LaBelle, but also regular folk. This is partly because of its price tag – the largest is $395 (£315). That might sound expensive – and it is – but compare that to other catwalk brands and it becomes relatively affordable in the world of luxury; a Louis Vuitton Speedy will set you back £1,310, for example, while a Chanel 2.55 is £8,530.

Lopez says this was intentional – it’s the kind of purchase someone can feasibly save up for (and they do – all but one of the designs are sold out online, and there are enthusiastic unboxing videos on TikTok). “I wanted to make a bag that I could afford when I was coming up,” he says. He says he sees people carrying the bag regularly. “I could be in one of those posh restaurants in London and then go to Brixton and a girl has that on there, too,” he says. “And it’s the same thing in Japan. I get pictures all the time. It’s pretty iconic. She [Ana] has a world of her own.”

He elaborates on how the design is a tribute to his family, who immigrated from the Dominican Republic in the mid-80s. “The handle was a homage to my grandmother and a nod to the Mod era,” explains Lopez. “And the shape was a nod to my mom. It’s like a briefcase … when immigrants came here, what they thought American luxury was, it was to have a briefcase. It’s a stamp of approval that you’re doing [well] even though you’re dirt poor. My dad had a briefcase in the house, and my mom had the small briefcase.” Is it a symbol of success? “100%. That’s what they were using it for, it was to fit into that world.”

The son of a construction worker and a factory seamstress, Lopez’s family and upbringing in the Dominican community are central to his designs, but also his lifestyle. He grew up in Williamsburg, long before the area was gentrified to the point of parody, and still lives in the same building in which he spent his childhood (although his parents have since moved to Long Island).

His mother and aunts showed him the power of clothes. “They were trying to emulate the American luxury they were seeing and to copy, paste – like a Latina Elizabeth Taylor or something,” he says. “But [they were] living in this dump. And to me, it was so beautiful. They were putting on these clothes to walk around these crack-infested neighbourhoods.”

after newsletter promotion

If Lopez’s relatives are one type of family that he draws on, there’s also his community of other young queer men of colour, who came up together in New York in the early 00s. The models in his shows are often women Lopez knows from the ballroom scene, the diverse LGBTQ+ subculture as captured in Pose and Paris Is Burning. This is also where he met Telfar Clemens, the man behind the label Telfar, who Lopez calls his “best friend”. The two are often compared – partly because Telfar’s bag is also another so-called accessible status accessory, with the biggest of his shopping totes selling for £211 (it has been dubbed the “Brooklyn Birkin”). Lopez has a note of impatience when asked about the comparison. “It’s like, why are they comparing us? Do they compare a Prada bag to a Fendi bag?”

Any narrative that they are competitors rather than friends is far from the case. “[Clemens] was always like ‘you need to do accessory’, he pushed and pushed,” says Lopez. “When I did my first drop [of the Ana] … he came and picked me up, popping bottles of champagne. We went to dinner to celebrate. They can’t break our bond.” Lopez says Clemens buys the Ana as presents for his relatives, rather than giving them his own bags.

Lopez is already fairly established in the fashion industry, beginning the label Hood By Air (HBA) with fellow designer Shayne Oliver (who he also met on the ballroom scene) in 2005, when Lopez was 17. If New York fashion at the time was pretty frilly dresses or work-ready shifts, Oliver and Lopez brought club culture, men in skirts and oversized logos to the catwalk long before other designers explored these themes. “We changed the game,” says Lopez now. “It took me a long time to be able to say that. I never gave myself my flowers.”

Lopez left HBA (without any conflict, he says) in 2010 and worked on various projects until Luar Zepol – a semordnilap of his name, later shortened to Luar – first began in 2017. But, after 12 years on the hamster wheel of fashion, the designer was reaching breaking point. “I was depressed and tired and exhausted, my mental health was all over the place,” he says. “Right after my show in 2019 I stopped completely and I disappeared into the Cayman Islands [he worked as a consultant to a hotel] and hid out down there for a year and a half.”

He says this retreat came from a realisation. “I never took a break since I left HBA. It was always go, go, go, go, go because even when I was stopping, I was still doing consulting. I was still working, trying to make money. It took a toll on me,” he says. “I’m always [the one] saying ‘oh, depression, anxiety. That’s crap, just snap out of it’. I didn’t know that I was actually depressed and had anxiety and my mental health was going through the sky.”

While he was concerned time out from the industry would mean fashion would move on, it actually proved to be the galvanising moment. “When I came back in 2021 I already had a business plan,” he says. “I figured out how to make my brand successful – not just make clothing to please my friends, the art world and the fashion girls.” As his Instagram bio semi-jokes, philanthropy is next. “I’m just trying to figure out a way I can give back to the people who helped me and who inspire me,” he says “Like trans housing organisations, immigrants. I would like to do different colourways [of the Ana] and the money would just go to organisations. I’m not rich but I don’t care. I’ve lived a life of privilege and I still do. I don’t care about the money.”

The Ana, meanwhile, has her own story. “Seeing my bag all around the world is beautiful,” he says. “I walked into a hotel and saw this woman and her mad crocodile Birkin and then she has my bag across her body. You go to Bushwick [a Brooklyn neighbourhood] and you see it [too]. That’s the world of Luar.”