In today’s world, most people have an awareness of what they say when it comes to cultural sensitivities and political correctness. You wouldn’t crack a joke about someone’s ethnicity, nor would you refer to a person by anything but their preferred pronouns. But have you given any thought to how your clothing can send an unintended message? From cultural appropriation to the stereotyping of genders, fashion has a long history of missing the mark. To understand this better, we spoke to stylists about the biggest fashion trends over the years that are offensive by today’s standards. Keep reading for a reminder of what you’ll never want to wear again.

READ THIS NEXT: 7 Hit ’80s Songs That Are Offensive by Today’s Standards.

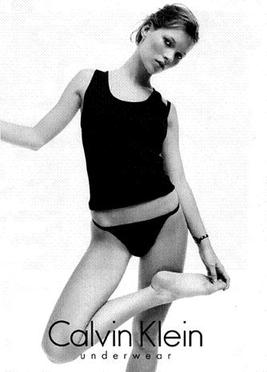

“Heroin chic”—yes, it was actually called that—was the “it” look of supermodels and the designer fashion industry in the 1990s. Simply put, this aesthetic featured “strung-out” looking, rail-thin models with dark circles under their eyes. It was popularized by photographer Davide Sorrenti, who died of a drug overdose in 1997.

“Magazine editors are now admitting that glamorizing the strung-out heroin addict’s look reflected use among the industry’s young and also had a seductive power that caused damage,” The New York Times wrote at the time.

In fact, even then-President Bill Clinton felt strongly about the trend. “You do not need to glamourize addiction to sell clothes,” he said, per The Guardian. “The glorification of heroin is not creative, it’s destructive. It’s not beautiful; it’s ugly. And this is not about art; it’s about life and death.”

And in today’s world, which has seen the effects of the opioid crisis, such a look couldn’t be any more offensive.

“Tribal” has long been a catchall word used to describe clothing that features historic motifs from Africa. One of the most notable examples is Kente clothing, made of patterned fabrics featuring gold, red, blue, green, and black.

“Its origins date back to the 17th Century in the Gold East, now known as the country of Ghana,” explained Spectrum News affiliate Bay News 9. “Back then, this delicate cloth was worn by Ashanti Empire Royalty and each woven color carries deep meaning.”

But as Elizabeth Kosich, certified image stylist, founder of Elizabeth Kosich Styling, and founder and chief creative director at The EveryBody Wrap, notes, wearing such clothing with no regard for its roots can be considered cultural appropriation.

“The dashiki—tunic-like traditional shirting from West Africa—is often glamorized by the fashion industry,” she says. “The tribal motifs can offend, too, so if something feels off, potentially exploitive or costume-y, take a pass.”

In another example of cultural insensitivity, Kosich points to American culture motifs, such as Hawaiian prints, Eskimo dress, and Native American designs.

“While these cultures have long been embraced by fashion, stereotyping them is cultural appropriation and offensive to all,” she says.

Farnam Elyasof, fashion expert and CEO and founder of Flex Suits, points to how Native American headdresses have historically made their way into mainstream fashion. (Victoria’s Secret featured them on the runway as recently as 2017—after having to apologize for the same misstep in 2012.)

“These headdresses carry significant spiritual and cultural significance for the Native communities, and their use by anyone other than Native people is viewed as deeply disrespectful,” Elyasof says.

READ THIS NEXT: 6 Classic Sitcom Episodes That Are Wildly Offensive by Today’s Standards.

Sally Samuels, head of design at Savile Row Company, recalls the 1960s and ’70s trend of “oriental” fashion.

“Nehru jackets, silken robes, and Asian-inspired motifs and patterns were all the rage, adopted by fashion icons and the average man on the street,” she says. “Instead of being an homage, this trend reduced these rich cultures to mere fashion statements, all under one offensive banner of ‘Orientalism.'”

A more recent example pertaining to South-Asian cultures is the bindi, which has “deep cultural and spiritual significance amongst South Asian communities,” Elyasof adds. “The use of bindis by non-South Asian people is a sign of disrespect to their culture.”

If you went to high school in the ’90s or early 2000s, you probably remember many male classmates “sagging” their pants so that the top half of their underwear stuck out.

“While it may seem like a harmless trend, it started in U.S. prisons where inmates weren’t allowed to wear belts, and was then carried into popular fashion by hip-hop culture,” explains Samuels. “But peel back a layer, and it’s clear that it was often used as a pretext for racial profiling and discrimination, promoting racial stereotypes against young men of color.”

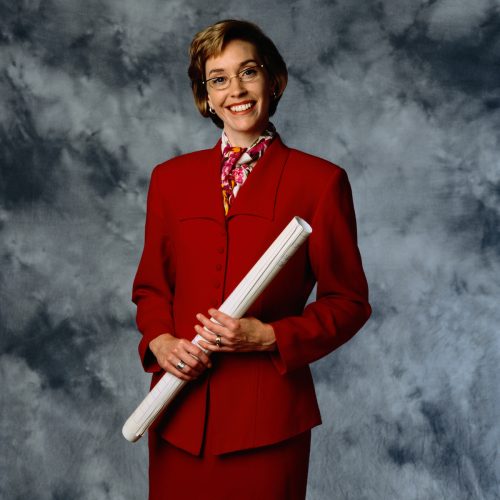

“Power suit” is a term used to describe the hard-edged, shoulder-pad laden, men’s-style suits worn by women in the 1980s and ’90s.

“A sign of prominence, prestige, and influence, the power suit defined cultural norms, capitalism, and corporate America in the 1980s,” says Kosich.

“In film and television, power dressing suggested that hard work and a little feminist ingenuity was enough to propel a woman to the top,” wrote The Atlantic, referencing Melanie Griffith in Working Girl and Dolly Parton in 9 to 5. And perhaps you’re conjuring up images of Hillary Clinton’s famous pantsuits.

And while The Atlantic makes the point that the power suit “opened the door for more gender-neutral fashions to enter the mainstream,” it also may have insinuated that, in order to be successful in the workplace, a woman could not dress too femininely.

Kosich also argues that, following a global pandemic when nearly all of corporate America was working from home, expecting such a dress code is now considered “tone deaf.”

Though it became most trendy in the 1980s, the origins of camouflage prints in streetwear can perhaps be traced back to Andy Warhol’s “Camouflage” prints, reported the Columbia Daily Tribune.

“Warhol showed that you could recolor camouflage in ’60s pop colors and make it a playful fashion print, edgier than a floral,” Hamish Bowles, global editor at large for Vogue, told the paper. “[Designer] Steven Sprouse took it up, recoloring it and using it for fashion garments.”

Since then, camouflage prints have been found everywhere from department stores to the runways, with combat-style Dr. Martens boots adding to the trend.

But “camouflage has a much different meaning to those in the military,” notes Kosich. “It’s not considered a cute trend to those who serve, and wearing camouflage in a stereotypical way can be seen as offensive. Camouflage as a fashion statement telegraphs disrespect to those who defend our freedoms.”

For more style content sent right to your inbox, sign up for our daily newsletter.

Long before People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) was founded in 1980, critics were vocalizing their objections to killing animals for fur and leather clothing. But in most cases, they were overshadowed by what was considered opulent and stylish.

“From raccoon coats popular in the 1920s to mink stoles sported by the most glamorous Hollywood stars of the 1950s and ’60s, the use of real fur was not questioned and was a standard part of fashion,” shares Samuels.

Kosich adds that leather and feathers also fit into this category. “These luxe items collide with pro-animal, pro-environment sensibilities and can offend in seconds,” says Kosich. “Consider faux leather, faux fur, and faux feathers instead, which can be just as luxurious but without the guilt.”

Fast fashion isn’t necessarily considered offensive by today’s standards—but it’s getting there.

“Fast fashion entails the production of cheap clothing that is designed to be worn a few times before being discarded once a new hot trend arrives,” explains Elyasof. “This business model is not only criticized for its environmental impact, but it has been shown to contribute to the immense exploitation of overseas workers and gross violation of their rights.”

“Companies like Shein continue to come under fire from consumers owing to their unethical and unsustainable business practices pertaining to fast fashion,” he adds.