The fashion industry owes a great deal to hip-hop. The rich music genre turned global force has inarguably transformed pop culture in its 50-year history, but its impact can be equally seen gliding down runways and etched into the fabric of luxury fashion brands like Dior, Gucci, MCM, and Louis Vuitton thanks to streetwear — better known as urban fashion or hip-hop’s signature style. It’s been rooted in hip-hop culture for decades now, boasting an estimated market value of $187.58 billion today (via Yahoo! Finance), and that figure is expected to increase well into the next decade. However, it couldn’t be reached without the pioneers who created the culture-shifting blueprint for the fashion industry — like trailblazing designer April Walker.

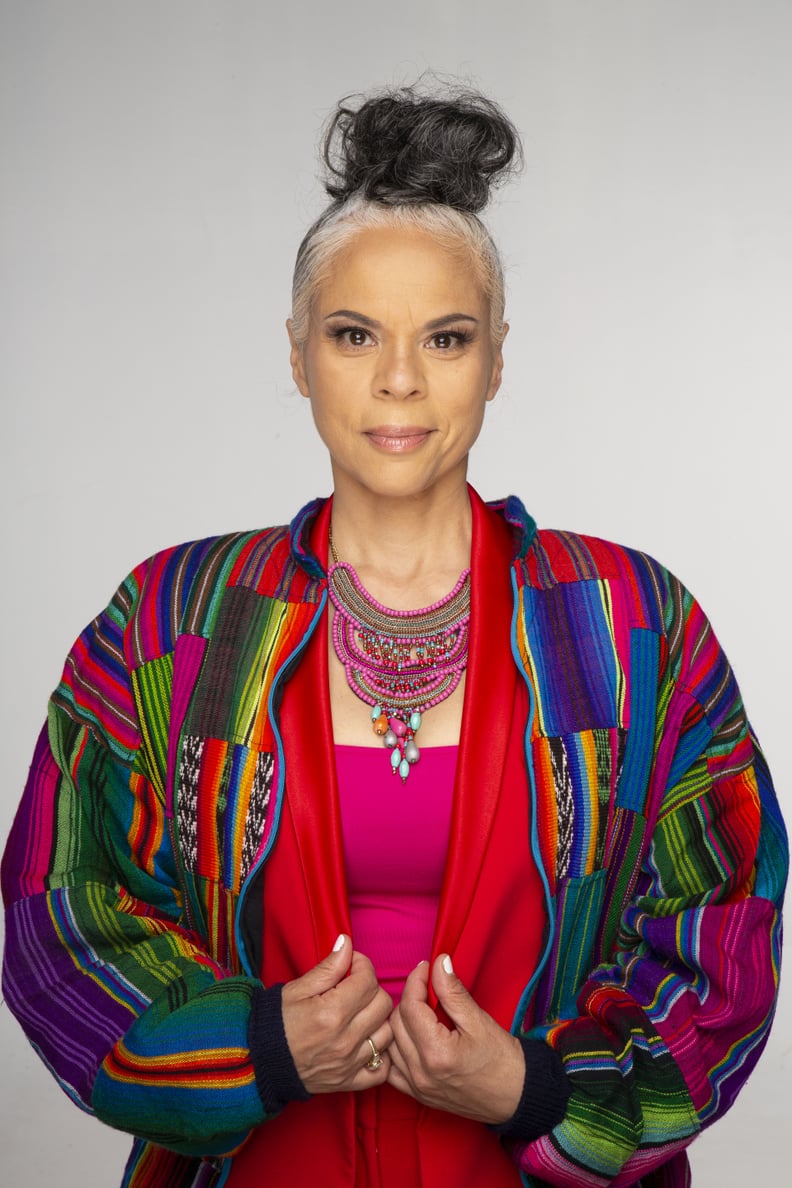

Walker is among the class of fashion innovators who paved the way for modern streetwear brands, designers, entrepreneurs, and stylists to thrive abundantly. Though the 57-year-old pioneer’s name is spoken in unison, her boundless creativity, business acumen, and intuitive thinking place her in a league of her own. Early on, Walker knew she didn’t want to work for anyone in the industry, so the then-21-year-old entrepreneur used her artistry to fill a void that would later become a billion-dollar industry.

“I didn’t think about what I couldn’t do.”

“We were already remixing our own clothes by airbrushing, and acrylic painting, and bling blinging, and bleaching them. But we couldn’t go in the stores and buy anything that reflected the lifestyle,” Walker recalls to POPSUGAR of streetwear’s origin story.

In 1987, Walker opened her first shop, called Fashion In Effect, during her junior year at SUNY New Paltz. Her atelier soon became a magnet for hip-hop culture, attracting graffiti artists, dancers, rappers, and hustlers to 212 Greene Avenue — located in her hometown of Brooklyn, NY — to both buy clothes and exchange ideas. It also brought about exciting new opportunities for the founder. When hip-hop duo Audio Two walked into Fashion In Effect seeking a Brooklyn-based stylist, Walker agreed and styled the cover for their 1990 “I Don’t Care” album. Unafraid to learn on the job, she then accepted Audio Two’s offer to style their video, establishing a new revenue stream and industry marketing tactic: product placement.

“I didn’t think about what I couldn’t do,” Walker says. It’s a mindset the Brooklyn native, who’s Black Mexican, credits her father with instilling in her and her two sisters, Jackie and Tahirih. Witnessing his entrepreneurial journey in the music industry — where he managed jazz artists and groups like D Train and also worked with rappers Jaz-O and JAY-Z — Walker saw firsthand the ins and outs of the business. And with a hustler mentality embedded in her DNA, the serial entrepreneur cultivated business relationships with other emerging artists in New York City’s hottest clubs in the ’90s. A sequined gown Walker wore and designed stopped Run-D.M.C. in their tracks at the legendary Club Kilimanjaro, and an exchange of cards led to another styling opportunity for her. Meanwhile, connecting with artists’ management teams opened more doors, too. After meeting Queen Latifah and Shakim of Flavor Unit, for example, Walker began styling hip-hop trio Naughty By Nature.

Most notably, the rise of Walker’s career birthed the first women-owned urban menswear venture, the iconic Walker Wear brand. Famous images from the ’90s showcase hip-hop legends such as Tupac Shakur and Notorious B.I.G. and former boxing champion Mike Tyson sporting the brand’s distinct logo, and its impact only grew. Walker’s signature fits, which include the rough and rugged suit, were donned by the late singer and fashion icon Aaliyah, former NBA star Shaquille O’Neal, and Rock & Roll Hall of Famer LL Cool J. Her brand also appeared in staple films like the 1994 sports drama “Above the Rim,” featuring Shakur.

Given Walker’s clientele, at one point, many assumed her brand was run by men. The founder and CEO admits she was ambiguous about the company’s ownership given the challenges women in leadership, and especially in hip-hop, faced back then. But she was clear on knowing how to navigate the male-dominated industry. “I knew when I had to speak up,” Walker says. “There were times when I had to speak up and chin-check men in corporate rooms. That was very uncomfortable, but I knew that if I didn’t do that, people would walk all over me.”

Other tactics Walker employed included knowing when to send a man to a meeting, wearing “safe” outfits to keep the male gaze on business opportunities at hand, and adopting a “no-nonsense attitude.” “I think that helped me because it probably intimidated a lot of men. But if they did do something that wasn’t appropriate, I let them know, and that changed the dynamics, and it didn’t happen again,” Walker says. “I stood up for myself when I needed to.”

Back in the ’90s, streetwear pioneers like Dapper Dan, Karl Williams of Karl Kani, Carl Jones and TJ Walker of Cross Colours, and Walker maneuvered through new territory in the fashion space while simultaneously breaking barriers together. The 1992 MAGIC trade show marked an industry-defining moment as Walker Wear, Karl Kani, and Cross Colours all joined forces to turn a conference room into a jail cell activation. Not only was the creative collaboration a daring move for streetwear, but it also solidified the position of the leaders shaping it in the fashion market.

With streetwear still seen as an emerging style, the MAGIC trade show organizers didn’t give the trio a spot on the main showroom floor. However, being underestimated only placed the designers in a position to win, as they each walked away with roughly $2 million in sales that day.

“It was really about basically taking the reins and being as creative as you could and using the resources because we didn’t have the same access to resources [or] funding,” Walker explains. According to her, back then, “You had to find a door and kick it in.”

Streetwear finally began to permeate the fashion industry in the ’90s following the emergence of lines like FUBU, Phat Farm, Baby Phat, Sean John, and Rocawear, as well as the continued growth of Tommy Hilfiger and Mecca, among others, as hip-hop rose. With this shift, shoppers beyond New York City were able to access streetwear outside of shops set in Harlem and Brooklyn, finding it on the shelves of department stores. The era-defining decade flipped urban fashion from a subculture indulgence to a global export, and those like Walker who were part of its origin story had a front-row seat to the changes.

“I want to leave an imprint on the world.”

During that time, many would say Walker was at the top of her game with showrooms in New York, Los Angeles, and Las Vegas, but she acknowledges that she was stressed, displeased with the rapidly changing fashion industry, and quickly falling out of love with it. She decided to press pause on Walker Wear in 1999: “I needed to walk away and know that I was OK.” She further reflects, “It was the best thing I could have done for myself, looking back, because I was able to really focus and understand what I needed, what success looked like to me, and what was important to me.”

The hiatus would later allow the entrepreneur to launch other business ventures and, when ready, relaunch Walker Wear in 2012 — leaving her with a well-respected track record in the streetwear game. With a nearly 40-year tenure in fashion, Walker’s legacy has been captured in programs such as documentary “The Remix: Hip Hop x Fashion” and “50 Years Fly,” as well as archived in exhibitions like “Women in Streetwear” (which she curated for NYC’s Port Authority Bus Terminal), Kunsthal Rotterdam’s “Street Dreams: How HipHop Took Over Fashion,” Museum at FIT’s “Fresh, Fly, and Fabulous: Fifty Years of Hip Hop Style,” and “¡Moda Hoy! Latin American and Latinx Fashion Design Today.”

Today, Walker, the author of “WalkerGems: Get Your Ass Off the Couch,” continues to share her knowledge of the fashion industry with up-and-coming designers and is launching WalkerGems Digital Academy to make this information even more accessible. “I want to leave an imprint on the world where when young Black and Brown people, specifically women, see that I did this in 1987, they absolutely can shake their head, like, ‘Oh, I’m doing this and I can do it bigger and better.'”