It was the deflated football that did it. The patchy field behind the apartment complex in Atlanta, Georgia, was miles apart – in every sense – from the lively streets of Amman, Jordan, where I grew up, but seeing a group of kids kicking that raggedy ball around took me right back to the barefoot street matches I played as a girl.

To me, there was nothing strange about asking to play with them. In Amman, anyone who wanted to play football would just ask. I grabbed a (fully inflated) ball from my car. What started as an impromptu match soon became a regular occurrence.

Of course, there were differences between playing in Georgia and Jordan. When I was a girl, we used tortoises for goalposts (not always successfully, as they tended to wander off). We all spoke Arabic and went home to comfortable houses. Many of my family members held powerful positions in business or government. In Georgia, the kids used rocks as goalposts; most of them spoke different languages and went home to cramped apartments.

The complex was in Clarkston, a suburb of Atlanta and one of the top refugee resettlement hubs in the US. Almost all the families living there had recently arrived in the US and were doing their best to rebuild their lives after fleeing war and persecution: navigating the unforgiving maze of US immigration policy, learning English, working long hours and facing rampant xenophobia.

As a refugee myself, I knew how isolating this experience could be. I left Jordan in the early 90s to go to university in the US. As a gay woman raised in a country where attitudes to homosexuality are extremely hostile, I had spent my life feeling out of place, forced to hide core parts of myself. I came into my own at university in Massachusetts and realised I would never survive a lifetime of suppressing who I was back home. So, when I was 21, I applied for political asylum, which was granted in 1997. My family disowned me when I broke the news to them that I wasn’t coming back. Overnight, I went from being the child of millionaires to having nothing – no family, no money, no idea how I was going to survive.

I spent a year washing dishes and scrubbing toilets. Then I landed a job in Atlanta coaching elite girls’ football. As I had played in college, they waived the training requirements for me. I loved my team and I soon got used to a life of privilege again. Football became about winning – about having the best and being the best, above anything else.

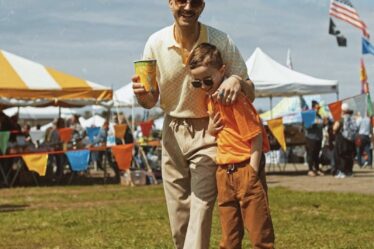

That is what struck me when I happened upon that game with the deflated ball. My job was less than five miles from that field in Clarkston, but it was a different world. The scrappy Clarkston crew eventually became a team – the Fugees. We stood out instantly: I was a female coach of black, Asian and minority ethnic players in a league where white kids and male coaches made up the majority. By the middle of the first season, the Fugees were walloping their opponents. The football team evolved into a study group, then a school – Fugees Academy – where we have built a trauma-informed, community-centred approach to refugee education that serves as a model for schools across the US.

As a society, too often we cherrypick the most exceptional “success stories” of refugees and immigrants, putting them on a pedestal instead of thinking about what it really means to succeed. Yes, I am filled with pride when one of our students is accepted to their dream university. But I am just as proud – if not more so – of the kids who fail and get discouraged, but get up and try again.

I am no longer the coach of the elite football team; running our non-profit, Fugees Family, takes up all my time. When I think back to that first football match, I realise it changed everything about how I define success. Now that I have young kids of my own, that lesson resonates even more. Yes, I am still competitive and want the best for my children. I want them to win – but I want them to play, rest and love themselves more. I don’t need them to have perfect test scores. I don’t need to be the perfect mother. What I strive for, every day, is to show resilience and a belief in myself that makes self-confidence second nature to them.

Believe in Them: One Woman’s Fight for Justice for Refugee Children by Luma Mufleh is published by Cogito (£9.99). To support the Guardian and the Observer, order your copy at guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply