One highlight of the recent fashion week in Paris was a club night hosted by Ezra Petronio, the busy, bearish Renaissance man who has had a hand in some of the industry’s most memorably cultish magazine and advertising visuals over the past three decades. Many of them are collected in a massive new book, “Visual Thinking & Image Making,” hence the party at the very venue where Jim Morrison spent his last night on earth. Petronio’s deejay roster spoke to his status in the Paris fashion scene: PR mage Lucien Pages, the Tellers Juergen and Dovile, Alaïa designer Pieter Mulier, stylist Carlos Nazario, and Nicolas Di Felice, who is busy turning Courrèges into a buzzfest.

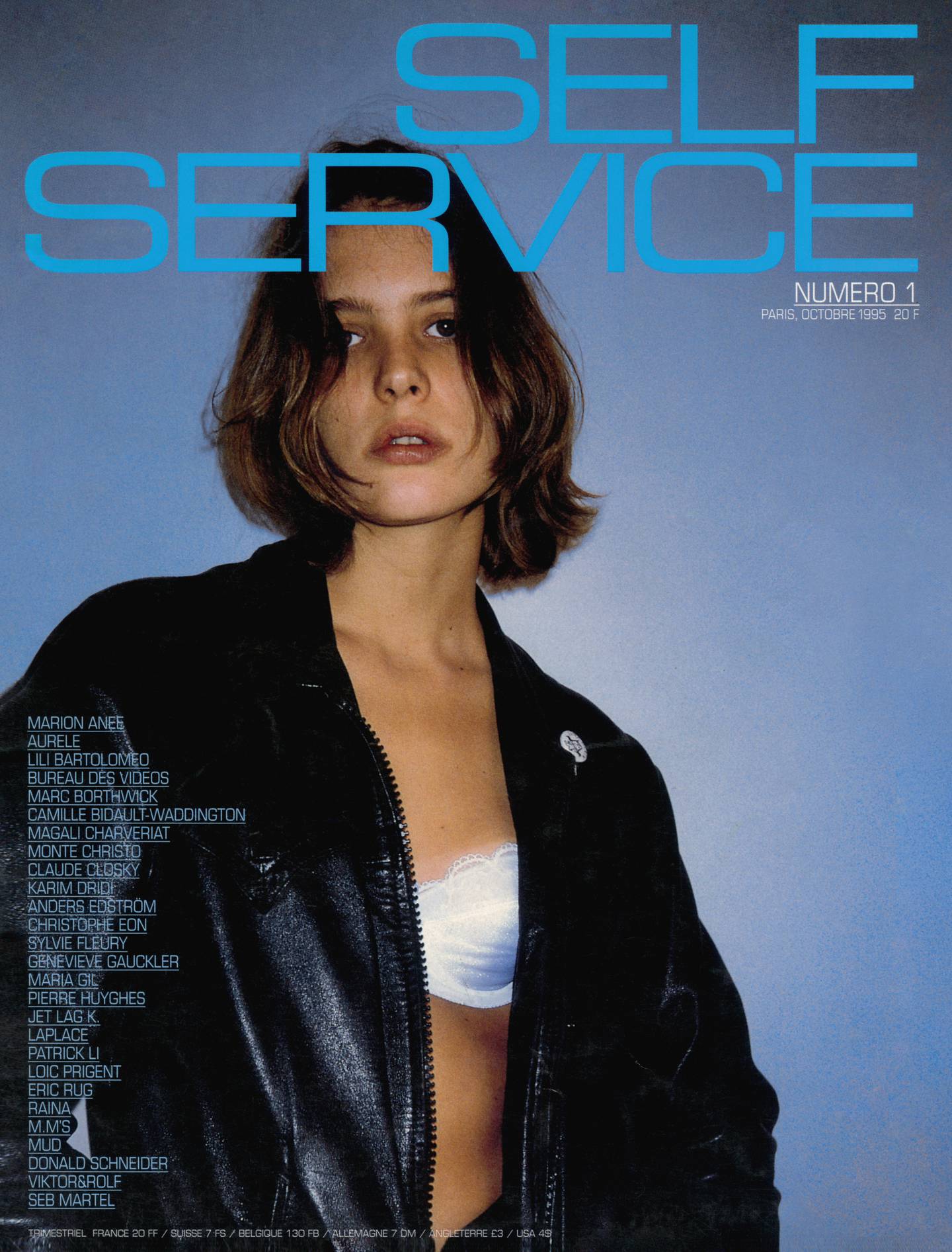

It’s often emotional for creative people to revisit their pasts, especially when they have covered as much ground as Petronio has in a career that stretches back to his creation of Self Service Magazine in 1994 with then-partner Suzanne Koller, but he had a more pragmatic agenda. He turned 55 years old in March and it was critical to him that “Visual Thinking & Image Making” not seem like some kind of sign-off. The magazine is booming and he has two agencies, Petronio Associates and Content Matters with now-partner Lana Petrusevych.

“I still feel like a puppy today,” he insists. “So this book is about clarifying the variety of things I do. Some people know me as ‘the Self Service guy.’ Some people know me as an art director, or photographer. It was interesting to put that together. But I also felt the need to restate what to my mind real art direction is, the way I learned it from my father, who was a great art director, or from people like Andy Warhol. It’s much more than deciding who is the latest photographer to use. It’s something that requires multiple skill sets, from copywriting to typography, from graphic, product and editorial design to publishing. It’s also really about your capacity to assemble ingredients, to surround yourself with the mindsets and talents to create a special context that enables you to do something unexpected. It’s the sum of all parts.”

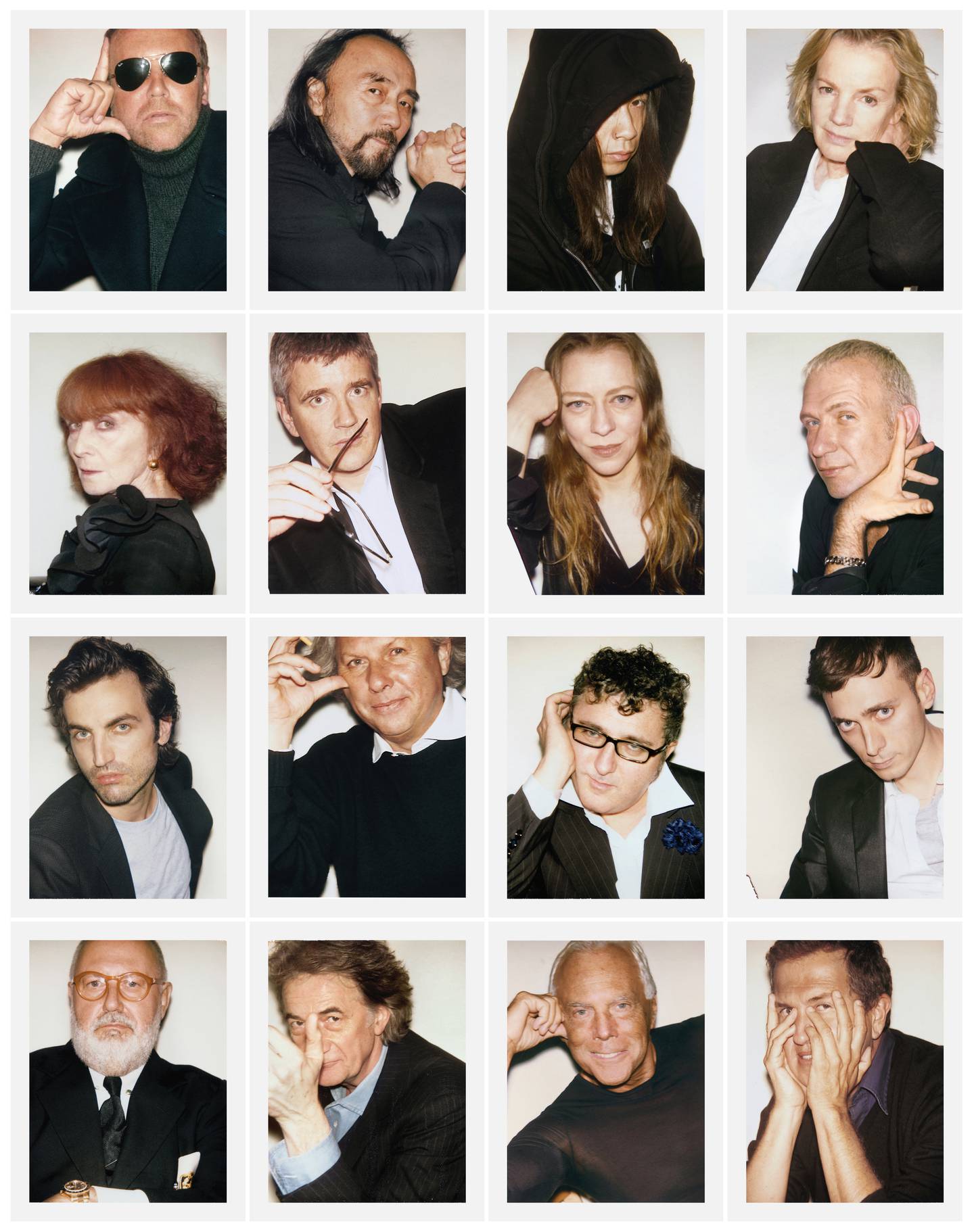

Being me, one of the parts I found most striking about a book that is so lavishly visual is that it is as good to read as it is to look at. Petronio insists that words have always been important to him. Despite having worked for a who’s who of luxury brands, he refers to himself a couple of times as a Marxist, and there is something of the political manifesto in the thoughts and themes that underpin his work. There is, for instance, a section called “Initiated Dialogs” in this book which features dozens of voices — designers, deejays, models, makeup artists, photographers, stylists, CEOs, other art directors — ruminating on how they maintain their creative integrity. “You are as good as the people you work with,” is a sentiment that Petronio expresses often, “and it’s nice to pay homage to all the different types of people that I’ve worked with. It’s nice also because we live in a privileged industry, and even more so today it’s quite exceptional to have the chance to be able to do the work we do.”

I’ve always thought there was an activist strand in Self Service, even if it’s not quite to the point where aesthetics become radical, like the Situationists. “I mean, none of us are really, really fighting global climate change. We are all part of over-consumption,” Petronio says. “People really fight for this idea of creative integrity and how to be progressive, and what’s the reason they’re working. I always write an editorial thinking not about myself but about the young people who are reading it, giving them clues or hints on how to best navigate this evolving complex industry. Maybe that’s the manifesto: giving hope to new people to not be overwhelmed, to remain themselves, because no one has the time to nurture their own personalities. A lot of photographers we’re seeing, they’re amazing, they’ll perfectly replicate the 90s aesthetic, but they’re too scared to say okay, we’re going to build on those references, go for something unknown. That’s what we’re fighting for: the capacity to do things we have not seen.”

There’s a conversation in the book between Petronio and Jefferson Hack, a kindred spirit who launched Dazed & Confused in 1991. Hack makes the point that founders like them have always been a bastion of independence against the corporate giants. But their original scrappiness has evolved over time. Consider the size of Self Service now: its physical weight could almost be a metaphor for its fashion industry heft.

“We evolved with our time,” says Petronio. “When we started in 1994, it was a different era. No Colette, no Internet, a very conservative time in Paris. We started the magazine with no money in a very hostile economy. I mean, I was American, we were not in the French mindset. It was very us against them, trying to gather people together to defend the new generation against the establishment. Our raison d’être was to support a new generation, like a kind of postgraduate programme for young photographers and stylists. And, as well as being a hub for new people, also enabling Juergen Teller or David Sims or Joe McKenna to find a place to express themselves, but all that with our own point of view on fashion, culture and society.”

“Yes, today it’s become maybe a much bigger machine. Our revenue has exploded over the last two or three years, which is also due to shifts in the publishing world. There are less and less magazines like ours, so we had to grow. The pages, the weight are due to the ad revenue, the advertorials, which take up more space. That being said, there was a lightness in the beginning, and we try to keep that today. We still like to explore and play. There’s always a sense of generosity and I think there’s also a place where we try as best as possible to be a space of conversation without hurting our relationships with brands. It’s harder and harder to be able to voice an opinion about things, because everything’s so transactional today in the industry.”

Which sounds, for all his professions of love, like Petronio’s view of the fashion industry has a shadowy subtext. For example: “I would say, kind of like a Marxist thing, everything is run by greed, the need for more and more. We look at these big mega brands, where all the other brands are trying to follow, the more they grow, the more they have to invest. It’s a very simple economic system. The more you invest, the more you communicate, the more you broaden your customer range. You’re caught in this economic cycle of having to grow, and very few brands are capable of maintaining their soul within that kind of evolution. And I don’t see that changing.”

“I think social media has disrupted our industry tremendously. It’s unfortunately led to a lot of entitlement in the new generation. You’re gonna post an okay picture and then Instagram is going to come and say Amazing Legendary Iconic. I was listening to this guy talking on a podcast the other day about how his work was going down in history and I’m like, guys, okay… the quality level is lowering and the sense of entitlement limits the journey these people take. In the next issue of Self Service, we’ve played with that idea. Everyone’s ICONIC, everyone’s MAJOR, everyone’s A SUPERMODEL, every story is THE GREATEST OF ALL TIME. I think that’s funny because maybe 10 years down the road, we’ll look back at this issue and see how it was representing our times.”

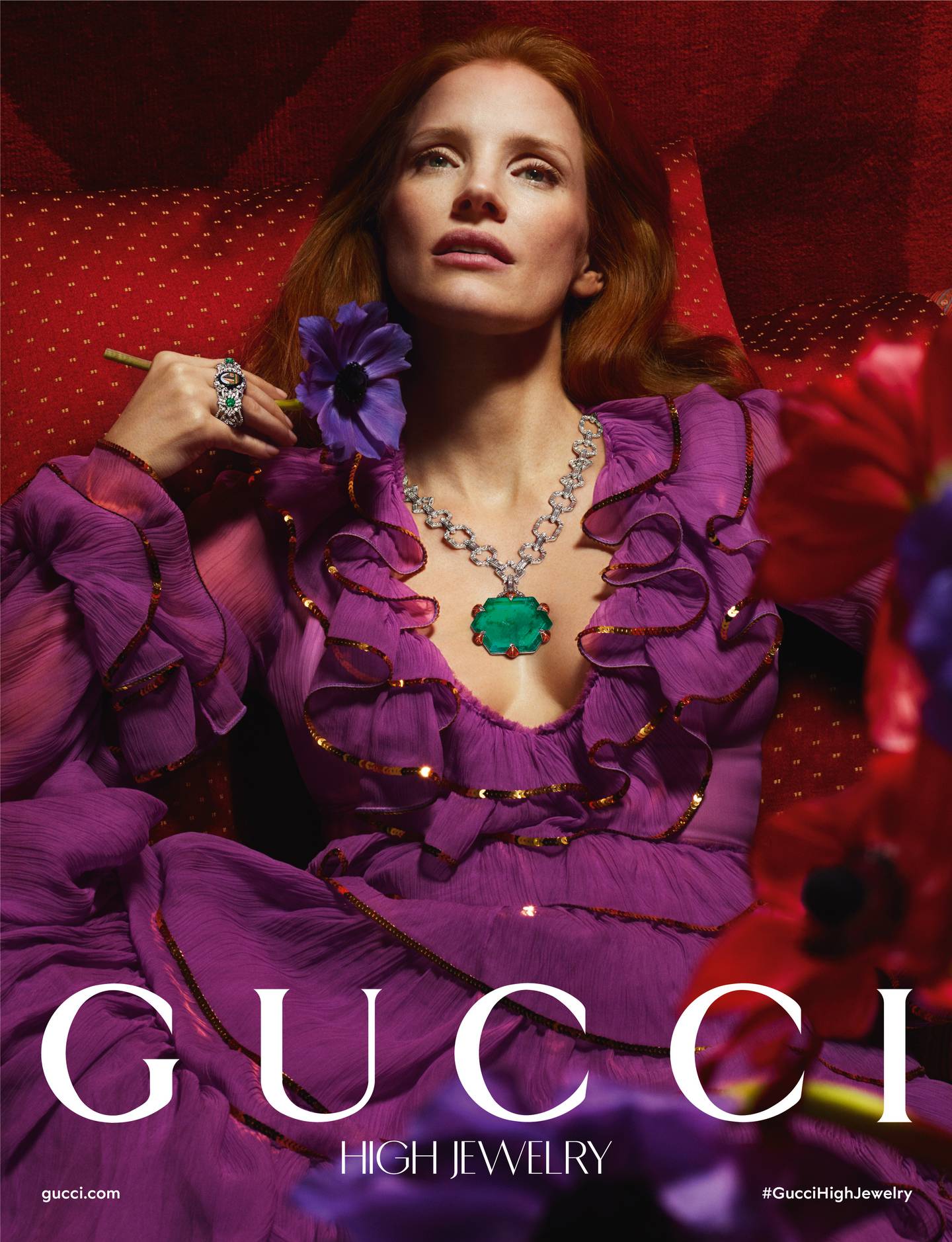

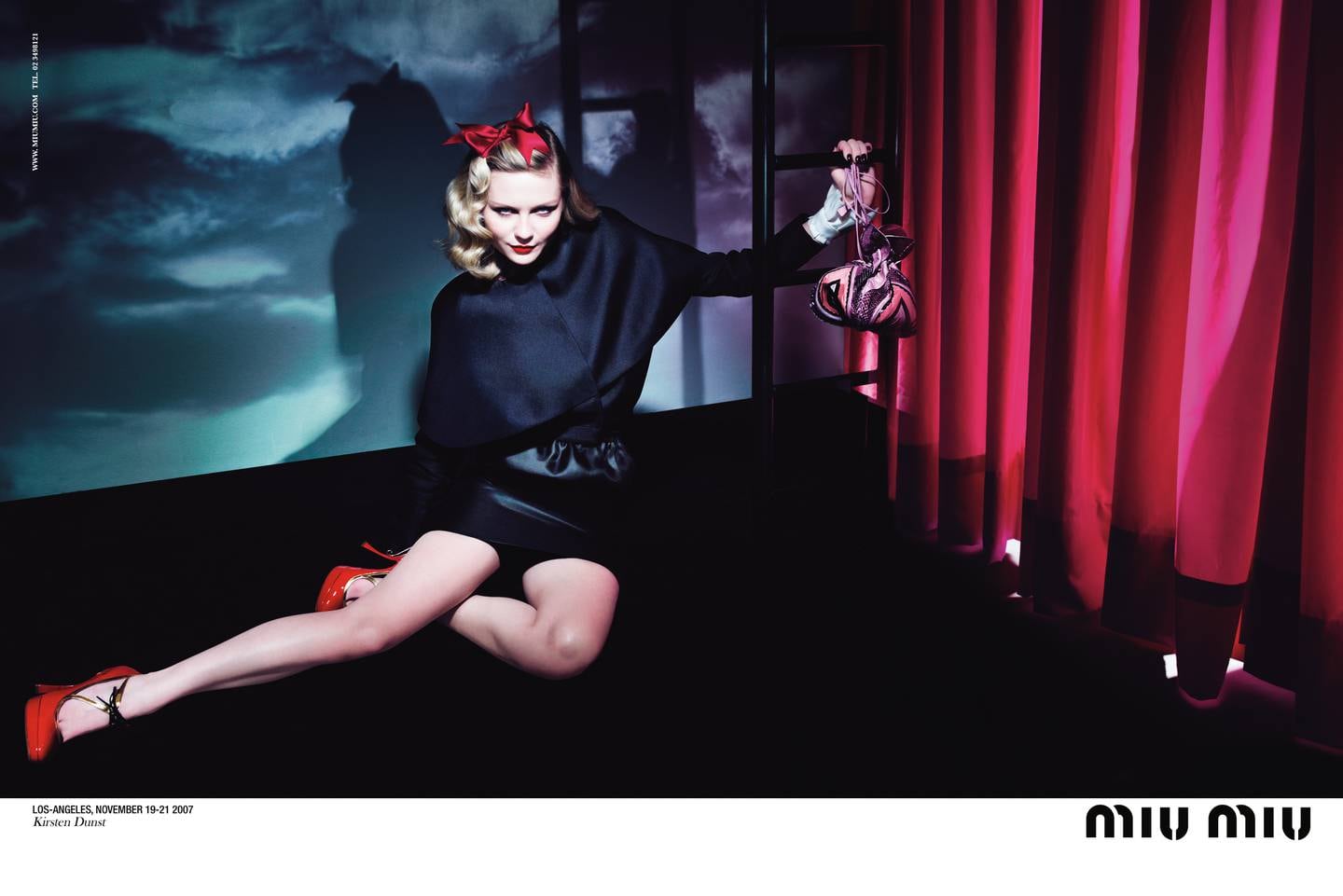

In the intro to Petronio’s book, he makes the sage observation that having nothing to lose is a proven stimulus to creativity. There is plenty of evidence within its pages of a prelapsarian time when brands like Prada, Miu Miu and Chloé were just starting to expand, when the appetite for experiment was still strong. “Whereas today, people want to know what works, so they apply existing systems. Now, when we work on a campaign, there are so many people in every brand and they all have their say-so and you end up having to convince everyone to agree on something. There’s no more place for magic and you’re kind of replicating the same thing.”

“It’s very easy to be nostalgic about the old days, but in the old days there was not the same level of capital in the business, so you had days to create a campaign or images that would encapsulate the designer’s vision for a season, and those images would live on in magazines and billboards. Today we do campaigns that live on the feed for five days, disappear, and are replaced by a new one. You have less time, you shoot one day with less budget and you have more assets to create, so you end up on these content campaigns, having to shoot ten pictures, ten videos, ten PDFs and all that retouching at full speed, so it’s out on Instagram two weeks later. It is harder within that kind of framework to try to do something exceptional. For all the work and difficulty in the past, we were doing images that were more memorable. Now you have to think very short term: What’s gonna shock? What’s going to impact us? It’s all very immediate. And then it disappears into this void.”

“I think it’s a bubble,” continues Petronio. “I hope it will burst at some point. But the only thing that can burst it is the consumer, if they really change. And I don’t see that. I get a little bit of hope from the under-25s. They’re coming up with a lot of culture and an understanding of what has been done in their creative fields. They look at the past, which is not true of every generation. Whether that brings any serious transformation, I don’t know.”

Something else that’s fascinating about Petronio’s book is that you can start at the first page and by the time you’ve worked your way to the last, you’ve had a practical education in art direction in all its manifestations. You have spreads on Saint Laurent and Chanel, research that was never published, images of metal plates used in foil stamping. “I like to focus on technical things. I had so many conversations when I was working with Jil Sander, sitting down and talking about little details of typography, that’s why I did a close up of that process.”

There are capsule case studies in brand building for the likes of Chloé and Miu Miu. And there’s some sterling instruction in dealing with clients. My favourite story involves Miuccia Prada, whom Petronio considers a mentor. When he was working on a campaign for Prada perfume, he commissioned his hero Irving Penn to photograph the product. Penn sketched out his idea, Petronio faxed it to Mrs P and, to his horror, she rejected it as boring. Give me something new, she demanded. Ezra was devastated. “Her attitude was, ‘I don’t want to be a follower, I’m not here to debate Irving Penn but I want something more.’ It’s nice to have those kinds of personalities who can still inspire you and teach you things.” (For the record, Steven Meisel eventually shot the campaign.)

And I understand now why Petronio refers to his tome as a transmission. “I like the fact that magazines like mine act as time capsules: the most creative ads, who was shooting, who were the faces, what were the clothes that were being made.” He has always seemed very conscious of capturing the fashion industry from that perspective. A few years ago, Self Service put out a charming little book called “The Vintage You” which featured once-upon-a-time photos of a couple of hundred fashion folk. The magazine also produced another publication that compiled several decades’ worth of advertising images. “Visual Thinking and Image Making” follows a similar trajectory: past, present and, at the very end, a QR code that is a portal to the future.

Then there are Petronio’s Polaroids, a comprehensive Warholian social document of the fashion industry’s great and good, famous and not so. “There is no more Polaroid film but I bought 40,000 flash cubes and we’ve developed a technical app that means I can use the Big Shot Land camera, the one Andy used, to capture the image digitally but still use the flash cube. It’s the first ever analogue/digital Frankenstein camera. So I can continue to use that same format.”

While he is so deeply engaged in the process of recording the fashion industry for posterity, does Petronio ever think about how he’ll be remembered? “It’s a hard question. I think as a lover of collaborations. Regardless of the medium I used, there’s always a sense of collaboration. That’s something that goes back to my youth and my parents and the way they were. My mom was a tap dancer, she gathered people to make shows. I ended up in high school putting a magazine together as the editor, gathering people as well. I like the idea they have something to say, something to fight for, something that they want to believe in. So being able to capture that in some way or another — whether it’s making advertising within a corporate context, recording the dreams and aspirations of a designer, or revealing someone’s personality in a portrait — that’s the way I like it.”