“Zero communication — none.”

That’s how one former Calvin Klein marketing executive remembers the brand’s acquisition by Phillips-Van Heusen (now PVH Corp.) in 2003. Two decades later, he still has vivid memories of the frantic months that followed the deal’s closing. With little information available, the rumour mill ran wild.

“We were all worried about ‘are there gonna be layoffs? Are we going to be absorbed into the master company? What was PVH buying exactly and why?’” the executive said.

Many didn’t wait around to find out. The executive recalls some two dozen corporate employees jumped ship in that period. (He stuck around, but now works for a different fashion company. He requested anonymity because he is not authorised by his current employer to speak with the media).

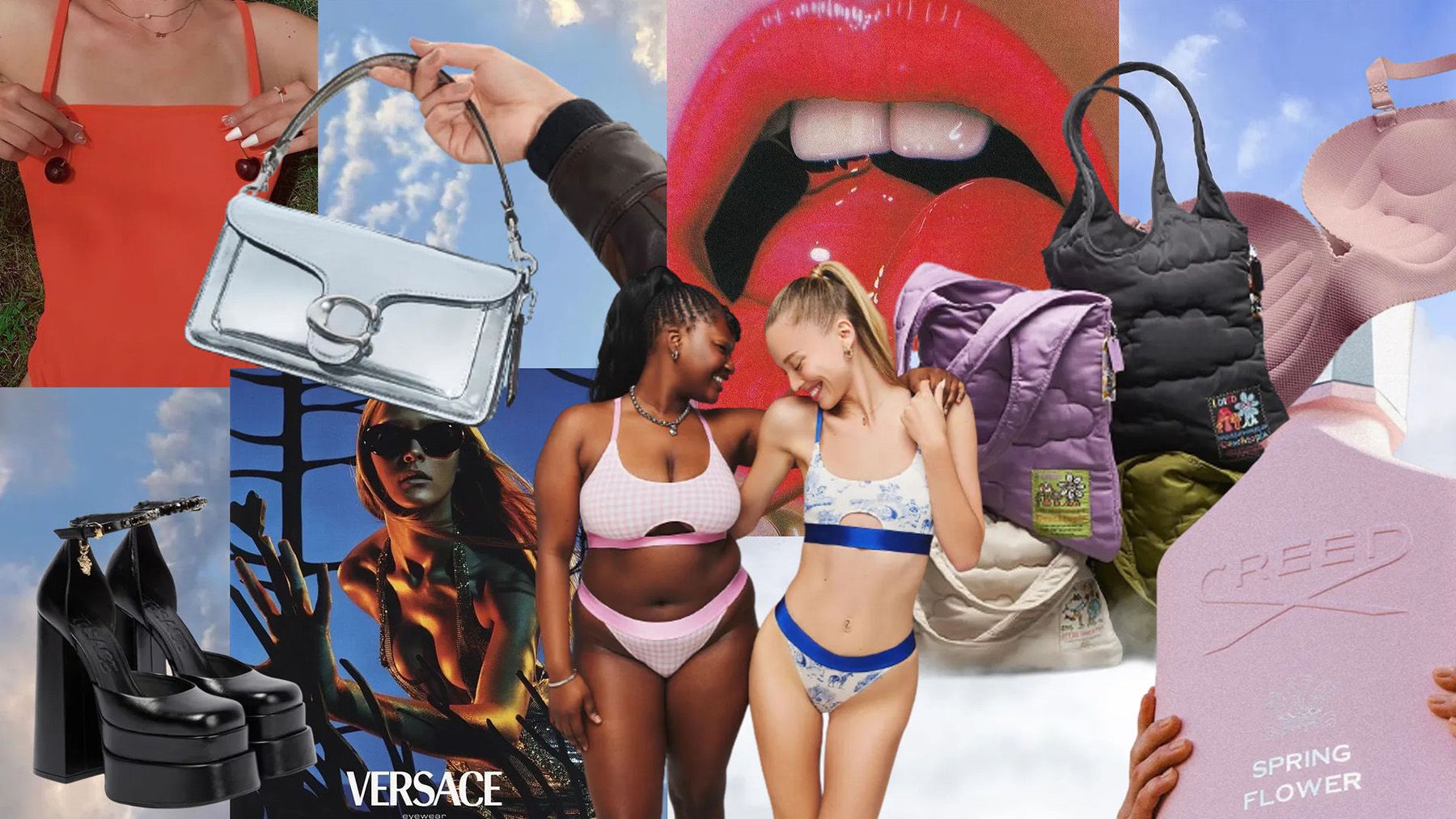

Recently, fashion deals have come at a frenetic pace. In the past month alone, Coach parent Tapestry agreed to buy Versace and Michael Kors owner Capri Holdings for $8.5 billion. Australian label Zimmerman sold to Advent International in a reported $1.5 billion deal and intimates start-up Parade was snatched up by Ariela & Associates International. In June, Kering purchased the fragrance house Creed.

The strategic objectives behind an acquisition are usually laid out in the deal announcement: buyers are chasing a bigger market share, geographic expansion, or see cost savings and greater pricing power from combining two former competitors. Often though, executives lose track of a critical component: the people who will determine whether those goals are met.

A hot brand loses some of its magic if the people who made it a creative and commercial force make a dash for the exit after a deal is done. Sometimes that’s intentional – Parade founder Cami Téllez told employees she felt she was being pushed out when the brand sold. But even if an acquirer wants to clean house, there are still likely to be high-performing employees — a social media genius, an IT whiz or a creative visionary — worth holding onto, experts say.

“The CEOs that we will talk to post merger will all tell us that you can get sucked into these types of activities — regulatory compliance, systems integration, accounting issues,” said Sherry Duda, senior client partner and head of the merger and acquisition practice at business consultancy Korn Ferry. “But when folks get it wrong, they’ll reflect back and what we hear is ‘I should have spent more time on people.’”

A Pre-Merger To-Do List

In fashion, deals are often structured to keep creative departments — like design and marketing — relatively independent while consolidation and drastic changes are focused in back office areas like finance and IT. That’s not always the case: LVMH replaced numerous senior executives after acquiring Tiffany in 2021 and overhauled its creative direction in an effort to move the brand upmarket.

As part of its Capri buyout, Tapestry emphasised improvements of backend operations like logistics, legal, human resources, real estate, wholesale distribution and infrastructure for digital marketing. Tapestry executives talked about using their superior customer data analytics to boost performance at Michael Kors and Versace, rather than shaking up the brands themselves.

In the best case scenario, executives from both sides of a deal agree on who will run key functions within the combined company. They can then create a new corporate culture — ideally a “best of both worlds” blend, said Michael Prendergast, managing director of professional services firm Alvarez & Marsal Consumer Retail Group.

It’s important that each stakeholder is honest and transparent about their ways of working — one company may be highly-collaborative and the other may be extremely competitive, for instance — so that all sides have a baseline of their similarities and differences, Duda said.

“Then, you can create a plan to address those differences in the future,” she said.

Once these ideals are defined, leaders can be more upfront and clear at the outset about the company’s future direction.

At Calvin Klein, there were fears – which proved well-founded – that PVH, then known for its dress shirts, was going to trade its new brand’s pop-culture relevance and fashion insider status for more mass appeal.

“In our opinion, PVH was a very different company than what Calvin Klein was, so there was a lot of hesitation about … how things would change,” the former executive said.

Calvin Klein sales swelled in the years after its acquisition, and PVH’s share price did too. But the brand’s status as a driving force in global fashion trends quickly faded. Efforts to revive that side of the business, including Raf Simons’ short-lived tenure as chief creative officer, have sometimes floundered.

Closing the Deal

Once a merger is decided upon, leaders should communicate quickly, clearly and confidently with their employees about what they expect to happen. Initial communication should spell out why the merger is happening and the major benefits for both parties, the potential growth opportunities for employees and the organisation’s plan to be “fair” to everyone involved, Duda said.

In almost all cases, some layoffs will be necessary and it may take several months post-close to determine job changes, Prendergast said.

“It’s much better to be upfront and transparent and let teams know that yes, all things are under consideration,” he said.

This can help employees “become part of the solution,” offering up their own innovative ideas or raising their hands for roles that emerge as the companies join forces, Prendergast said.

While layoffs are often top of mind for employees during a merger, there can be benefits for employees and the company culture as a whole.

“Sometimes, you’ll acquire a company that’s more agile and it’s a culture benefit to not have to go through seven layers of leadership to get stuff done,” Duda said. “Or maybe you’ll merge with a company that’s more flexible on the whole remote working thing.”

The Calvin Klein marketing executive was still at the company when PVH purchased Tommy Hilfiger in 2010. He recalled the email he received informing employees that they would become eligible for a new and more attractive competitive benefits package following the deal’s close. The package included more paid time off and a salary bump for those on the lower rungs of the scale — all benefits inherited from Tommy Hilfiger.

The existence of such an email itself was an indication that PVH had learned some important lessons from the Calvin Klein deal, he said.

The most successful post-merger employees are curious and demonstrate “a positive bias” towards change, Prendergast said. They position themselves as an “active voice in the change” and seek out ways to show their value and strengths. Employees are looking for signals from their new management too: inconsistent communication and an emphasis on cost-cutting over other concerns may be a sign it’s time to look elsewhere.

“Senior executives we talk to want to mine for good talents in the acquired company,” Prendergast said. “Don’t get caught up in the fact that you’ve been acquired and there might be impending reductions — step back from it, look at it strategically and figure out how to be successful in the new world.”