Welcome to BoF’s Weekly Technology Briefing, penned this week by senior correspondent Tiffany Ap and delivered every Wednesday. Not yet a subscriber? Sign up here.

Dear BoF Community,

If there’s ever a time when customers expect clothing to fit perfectly, it’s their wedding day. But the status quo for brides seeking the most flattering fit is often expensive and time-consuming alterations that can add hundreds of dollars of charges to an already pricey purchase.

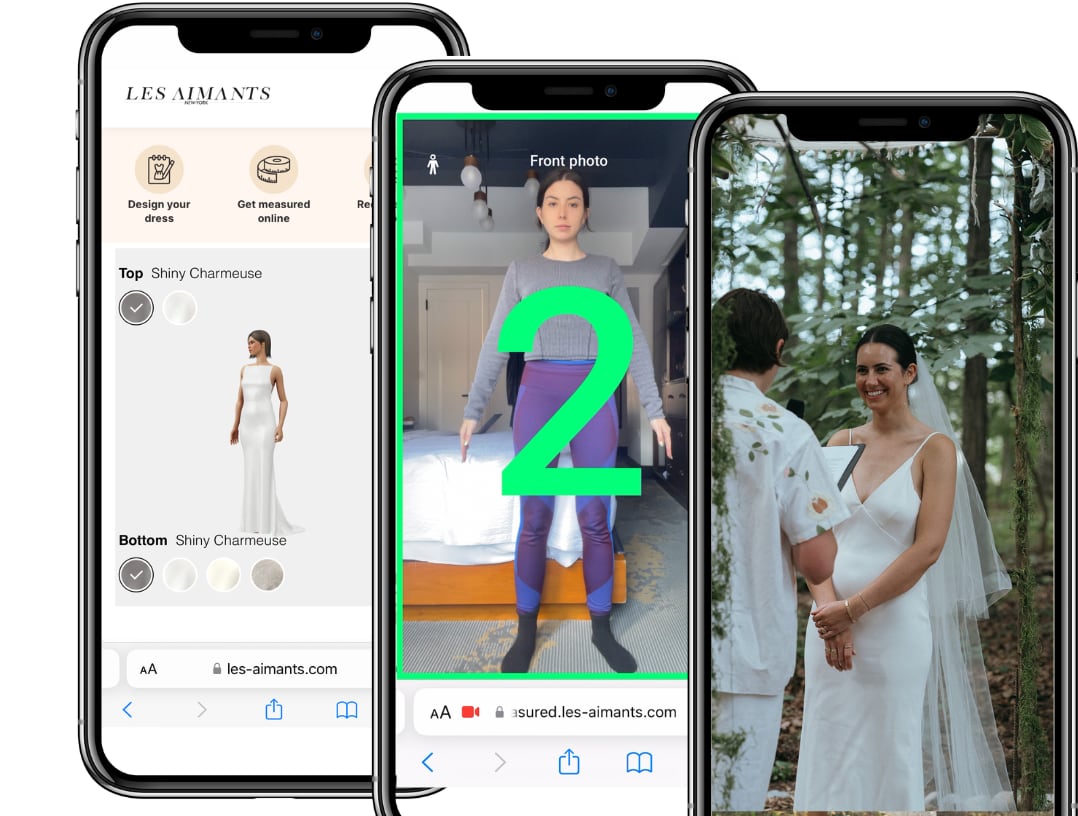

Start-up Les Aimants hopes to transform that experience by using a 3D body-scanning app to provide shoppers a custom dress with a made-to-measure fit.

The New York-based company which launched in 2019 allows brides to design a wedding gown online in a process similar to a bridal Build-a-Bear: They pick from a range of necklines, such as sweetheart, bandeau or off-the-shoulder, and select a bottom silhouette, like A-line or trumpet. Then using the Les Aimants app, they take a 3D scan of their body, spinning around slowly as the phone records 50 measurements. The app creates a digital avatar that lets the shopper visualise the fit of their dress.

Les Aimants produces and delivers their order in eight weeks, much shorter than the four to six month lead time many traditional dress designers require.

Fashion companies have been trying to use phone-enabled body scans to solve the problem of fit in online shopping for years now. Perhaps, the most high-profile effort was the ultimately unsuccessful attempt by Zozotown, Japan’s largest e-commerce player. But those endeavours have generally focused on apparel basics, which haven’t proved the best use of the technology. Customer requirements often aren’t as high for these products. An item from Uniqlo or Old Navy works well enough for most shoppers.

“As of today, how the fashion industry is running, you do not need to have a T-shirt that is made to fit your exact body’s measurements,” said Les Aimants founder Manon Martin. “We are taking on underrepresented markets.”

Bridal wear customers tend to expect the best, even if they are the type to be satisfied by an item that’s good enough when it comes to other kinds of clothing. And currently, the 140 million women in the US that get engaged annually face limited options in where they shop for their wedding day. The bridal market is highly fragmented, predominantly offline and skews to two poles: expensive luxury gowns that entail long waiting periods, or mass retailers like David’s Bridal, the largest bridal retailer, which recently declared bankruptcy.

Martin argues her company is filling a void in the market, not competing in a crowded category.

Previous attempts in 3D-fit have yielded underwhelming results. Zozotown launched its stretchy, dot-covered bodysuit, called the Zozosuit, in 2017, saying it allowed the company to take 15,000 precise measurements of users who scanned themselves with its app. Those users could then order basics that Zozotown would nearly custom-size to their specifications, ranging from $22 T-shirts to $58 jeans.

But the fit of the clothing garnered mixed reviews, and the product took weeks, or even months, to ship — much longer than the company’s original two week promise. After pressing pause on the project, it relaunched the suit as Zozofit, a tool to track weight loss and body-shape changes.

Unspun.io is another start-up that’s tried 3D fit, though exclusively for denim. Founded in 2015, the company charged $200 per pair of on-demand, custom-fit jeans. This past June, however, Unspun announced it would go in a new direction. Although the consumer-facing 3D-fit denim business is still ongoing, the company, which says its core mission is to pioneer sustainable ways of fashion production, is focusing on B2B sales for its new 3D weaving technology.

Wedding dresses, however, have numerous variations in shape, and fit requirements that go along with them. A 3D body scan can also more accurately portray details like a person’s posture, which can dramatically impact how a garment drapes, compared to a series of linear measurements taken by a tailor, according to Martin.

“Women do not all stand the same way,” she said. “We’re not only caring about your body measurements but really how your body sits because then it affects how we’re building the garment around that.”

Martin is confident enough in her software that alterations won’t be necessary or become a drag on the business. She said only very small changes have been needed for her 300 some clients thus far, or have been due to the bride changing their mind. But any changes are included in the upfront cost of the gown, which runs from $2,500 to $3,900. At a traditional retailer, alterations can easily add on $500 to $1,000 to the price of the garment.

If there is further manual tailoring needed, Les Aimants’ 75 percent margin could conceivably absorb that and still turn a tidy profit, which lower-priced products don’t allow for. The start-up is already profitable, according to Martin, and on track to do $300,000 in revenue this year.

Although the business is still nascent, she believes the technology and model could allow it to eventually expand to other areas of fashion where a precise fit is a differentiator.

“We have the data of their body measurements, and tomorrow we can offer them to make a perfect-fitted suit for women working in a fast-paced environment,” she said.