My daughter Tsubamé was born on 26 July 2013. I don’t remember what we ate for her first Christmas. I had to ask Hiraki, my husband, who we had over to eat it with. And as someone who now owns four boxes full of Christmas decorations, I don’t remember decorating a tree either.

What I do remember is the warmth that came from my mother’s friend, Hazel, being there too. I’ve known Hazel since I was born. Late November that year, she had emailed us to ask if she could come and meet Tsubamé and stay over. She was 61 and headed to Saxmundham, Suffolk, for a short course in care work and wasn’t sure where she’d then be posted for the three months of her stay.

In the days before she got in touch, I called my mother, in France, in a state. Our landlord had decided to put up our rent by £284. So I’d found a studio flat – upstairs in the same house – for me, Hiraki, Tsubamé and our two cats, but I really had not yet figured out how I’d get the move done. Also, although I was on maternity leave from my job, I was working with Hiraki on a film, composing a soundtrack for a show opening in mid-January in Tokyo.

The disturbed sleep of new motherhood was brutal. When Hiraki was away for work, I didn’t sleep at all. “Recently I’ve found myself swaying even when I’m not holding her,” I wrote to one friend. Another friend came over for an afternoon when I told her I was hallucinating. I’d been on the couch trying to feed Tsubamé and had reached out for my glass of water. Only there was no glass.

Perhaps more than the logistics and the exhaustion, I was wrestling with how to mother. That Christmas, breastfeeding remained confounding. “I’ve had these boobs my whole life,” I’d rail. “If they had one job, surely this has to be it.” But I couldn’t do it. And if I couldn’t do that, what else wouldn’t work? “An answer will come,” my mother said. Then Hazel came back.

We had the keys to the studio flat three weeks early. Hazel hadn’t found a placement after her training, so I suggested she return to London. She could stay upstairs while we remained downstairs. It was mid-December. She would be with us for Christmas. I bought her warm socks.

It would be easy to paint this simply as a perplexed new mother being comforted by an older, wiser other mother. But Hazel was just as much at sea as I was, only on the opposite shore. She had married at 22 and had the first of her four children at 24. She’d lived on farms and never travelled alone or left South Africa (save for Zimbabwe) until now. She was learning to navigate the world on her own after four decades of being a mum. I was only just getting started.

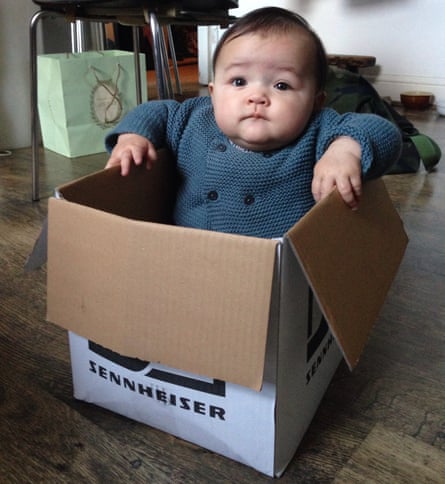

Hazel suggested I put Tsubamé in a cardboard box, so I could get stuff done. She’ll be safe, she said. She’d propped up all four of her babies and her nine grandchildren in a laundry basket while she hung up the washing.

So we buttressed Tsu with cushions, a crocheted blanket, a rattle and a soft-eared bunny called Denki and planted her on the living room floor. For the first time in months, I unfurled. “It’s quite something to have no mum around,” Hazel’s daughter had written after her departure, which is exactly how I felt, too. My parents, who lived in France, were unable to come until January as my father, a pastor, was working over Christmas. I spoke with my mother every day, and played James Taylor at Christmas because that’s what my father does. But there were moments when I needed their stronger shoulders. Now I had Hazel’s.

I helped Hazel register with HMRC and made us rice bowls for lunch. She held Tsu when I needed to work with headphones on. I took her cups of tea. Mostly, we didn’t try to fix each other.

What kept us focused was this tiny baby girl. Tsubamé means “swallow” – like the bird. Hazel said just holding her gave her hope. She called her “my angel”, which lands differently when crooners all around you are singing about cherubim. We didn’t have a star atop a tree but we did have that baby’s smile.

I bought a dozen all-butter mince pies and branches of red berries for Christmas Day. Hiraki vaguely recalls dinner being okonomiyaki. “Thank you for including me in last night’s meal,” Hazel emailed me from upstairs on 26 December. “It really meant a lot to me.” She once told me that she has a chair in her house just for hugs, no words needed. Every time Tsubamé wakes up, all hot with sleep and wanting a lap to sit on, I think about Hazel’s quiet, loving presence. Being with her that Christmas meant the world to me, too.