‘I spot-clean for a month and look no more dishevelled than usual’

I feel I should begin by airing my dirty laundry: I’m a middle-aged mother of small children who doesn’t do any of the laundry in our home. I know, I’m like the level of plastic particles in our waters: unprecedented. But it’s my sartorially fastidious partner, Claire, who does the laundry while my duties include walking the dog, cooking, cleaning, shopping, birthing babies, wiping bums … all of which casts a spectrum of stains across my wardrobe. So when I’m challenged to wash my clothes less – which is one of the small ways we can individually reduce the aforementioned microplastics entering the ocean – the first thing that happens is a row with my partner over the sensitive question of whether I can claim to “wash less” considering the small matter of not actually doing any washing at all.

Still, I can aim to put less in the laundry basket. I begin by carrying a microfibre cloth everywhere I go, ready to stab at stains as soon as they appear, Lady Macbeth style. I highly recommend it as a domestic war weapon. But does it lighten the laundry load? It does! It turns out an entire medium-sized Uniqlo lamb’s wool jumper does not need to be washed if I drop toothpaste on it. I just cloak my index finger in microfibre cloth, dampen with cold water, dab and go. I spot-clean jumpers, jeans, trousers, and shirts for a month and look no more dishevelled than usual. Result!

As for deciding when to put stuff in the wash, my general rule is if it hasn’t directly touched a body part, don’t bother. I end up putting less clothes in the wash even if it means spending an inordinate amount of time sniffing the armpits and crotches of my garments. It reminds me of when I used to see mums lifting up their babies in public to smell their bums and thinking “good God, never!” How little we know ourselves, in the end.

When we do put a wash on, we use a three-hour eco-cycle – the machine uses less water and a lower temperature – and I don’t notice the difference. I have also picked up other life hacks: wearing an apron when cooking, tucking trousers into socks when I’m walking the dog, hanging clothes on the line to air them on blowy days.

My children, meanwhile, continue to chuck their clothes in the basket, by which I mean to the floor, every five minutes. It’s starting to feel like a metaphor for the climate emergency in which, naturally, I’m the spot-cleaning warrior and my children are the climate-wrecking billionaires responsible for more carbon emissions than the poorest 66%. It doesn’t mean I’m going to stop trying, but it does mean there’s only so much I can do.

Chitra Ramaswamy

‘I’ve extended the life of two jumpers in just a few hours’

I have enough jumpers, but they are looking ropey. High street knits aren’t known for robustness and then there are those thieves of cosy joy: clothes moths. An inventory reveals seven of my woollies have holes; one black jumper is practically a colander and my favourite stripy Uniqlo knit is more hole than sleeve. I’m desperate to fix it and the others need some TLC to remain wearable. What can I do?

Thankfully I’m asking myself this at the right moment: the mending movement is huge and visible darning is part of that. Some visible mends sit on the frontier of art and craft: textile artists such as Celia Pym and Hikaru Noguchi explore the beauty of repair in their work and the stories it tells about our relationship with clothes. For beginners, YouTube is packed with helpful how-to videos; there are also kits, workshops and Zoom tutorials.

I go one better and ask Jane Mercer, a textile artist who volunteers at the Groves Repair and Share cafe in York, to show me the ropes. We start simple, on a practice square of fabric, as Mercer explains how to gradually build a lattice of threads across the hole with a tapestry needle and wool. I have no sewing skills – I barely manage buttons – but this is easy to understand, plus the visible mending technique of using contrasting colours makes it easier to see what you’re doing. My darn is wonky, but I get it done.

Buoyed up by this success, I buy some pale blue wool to tackle a modest hole in a grey jumper. It takes me hours; I unpick my work multiple times and get frustrated with my own ineptitude, but the end result is definitely wearable.

Before tackling my Uniqlo sleeve – the Everest of mends for a novice – I ask knitwear designer and visible mending expert Flora Collingwood-Norris for advice. She thinks a darn should work and I shouldn’t be intimidated by the scale: “There’s nothing radically different about big holes. They just look scarier and take longer.” What really lets me lose my fear, though, is when she says: “As soon as it becomes visible mending, there aren’t any rules you’ve got to stick to. By making it visible, you’re telling people that you decided it was going to look like that, so all you have to do is wear it with intention.”

That feels so freeing – permission to be a bit rubbish – so I get stuck in. It takes me three sessions, the red wool I have picked is extremely uncooperative, but I end up with something I’m not totally ashamed of. My mend is what Collingwood-Norris calls “an impressionist painting” (OK, from a distance and chaotic close up) but who except me will know? I’ve extended the life of two jumpers in just a few hours and gained a real sense of possibility: I can do this and I will again.

Emma Beddington

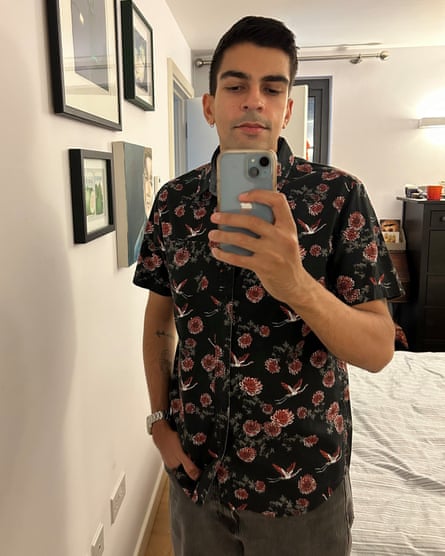

‘I was surprised at how much was lurking in the rails’

Unfortunately, I’m colour-blind. Blues and purples, reds and greens, oranges and browns – and much in between – all merge into one. This means that ever since I could dress myself, I have acquired a number of questionable looks. My teens saw me in the neon-glow of Topman nu rave, then there was a foray into flannel, a brief stint in Hawaiian shirts, trousers that were far too skinny, and finally my current style, which is a lot of the same thing: jeans with oxford shirts.

I have done a few culls of my wardrobe over the years and sent old items for recycling or to charity, but somehow it always remains full. It wasn’t until completing a “wardrobe audit” that I realised how unchanging and wasteful I am.

In recent years, apps such as Whering and Indyx have sprung up to help us work with what we already have rather than constantly being drawn to new purchases. You take a photo of each item in your wardrobe and the apps use them to create a digital catalogue that helps you work out which items you wear most and what to do with those you put on least.

Taking a photo of all of your clothes is laborious. But I was surprised at how much was lurking in the rails: a butter cream silk shirt that I can only assume I got for fancy dress, thermal leggings and half a dozen formal white shirts.

After three weeks I ventured into my “stats”. I found that I wore the same four button-down shirts 80% of the time, while two pairs of jeans made up 90% of my bottom-half choices. After reading some wardrobe audit advice, I began trying on my least worn outfits to decide whether I should keep them, sell them, or send them off to charity. This was followed by a questionable trip to the supermarket in a pair of baggy white jeans, a video meeting in silk, and a gig in pink linen.

Surprisingly, wearing these rediscovered clothes didn’t make me feel like an eyesore – if anything, it made me want to inject more colour and variation into my wardrobe, even if I don’t always get the combinations right. I might have stood out from the crowd but maybe that’s OK – it’s better than dressing like Mark Zuckerberg, trapped in a uniform of efficiency and boredom.

After a month of wardrobe auditing, it was the staples such as the endless white shirts that I decided to send to charity so I can make space for the clothes I previouslylackedthe confidence to wear. There is worth in wearing and adapting what we already have, to make sure our changes in style don’t always mean new purchases. When we do buy, we can look sparingly, for something unique. In my case, however, one silk shirt is probably enough.

Ammar Kalia

‘I’m keen to see if I can recoup some of the money I spent’

Here’s the thing: I have too many clothes. Not too many outfits to choose from – rather I have a small selection of clothes that I actually wear and a wardrobe’s worth that I haven’t looked at in years. I am aware that this is entirely a problem of my own making – and a privileged one at that.

It has become what I call my “eBay backlog”: items I have kept, intending to sell, for decades now. These aren’t beautifully crafted, investment pieces that I always planned to keep for ever: regrettably (but predictably) they are student-budget-friendly fast fashion, mixed with grungy vintage “gems” and non-refundable secondhand purchases that never really fit me. I could just donate them all to charity – but I’m keen to see if I can recoup some of the money I spent first.

The Vinted app has been a gamechanger for selling clothes. Similar to other resale sites, you take photos of the items, write a quick description and upload – but it’s quicker and simpler to use than other places like eBay. Even so, my backlog has remained. I would set aside entire days to list everything, but invariably find myself distracted by other things. Perhaps, then, the key would be to tackle my secondhand heap drip by drip, pledging to list one item a day to avoid feeling overwhelmed. It started well: I’m a sucker for routine and settled into a dinner-telly-Vinted groove. The mountain began to appear less insurmountable and items started to sell. Vinted tracks your cumulative balance and, as app-induced dopamine hits go, it could be worse.

But, occasionally, I do like to go out or go away and that meant I got behind on my selling. So I turned to a third-party seller to help me. Stae is a secondhand store that sells on your behalf in return for a cut of the profits. I offered founder Jenna 10 items and she agreed to take half; that’s five days “off”.

It all helps. Slowly, the hoard dwindles. Long-ignored clothes are parcelled up and posted to new homes. The challenge, of course, is to not buy as much as you sell; Vinted is a den of temptation for anyone with an eye for a fashion bargain. But in terms of shifting to a more sustainable way of shopping, it still feels like a good habit to develop.

Leah Harper

‘This is the appeal of going to a tailor: altering clothes to be bespoke, so that they are a pleasure to wear’

When it comes to clothes, I find people tend to be minimalists or maximalists. This was apparent to me while growing up, when my younger sister had an ever-expanding wardrobe of high-street purchases, the majority of which she didn’t seem to wear. I, meanwhile, have always found shopping to be more stressful than rewarding.

I don’t hang on to clothes out of sentiment – not least because of space restrictions – and bestow those I will never wear again to the local charity shop. But I do have clothes that linger largely unworn because they don’t fit or they need fixing and I don’t have the skills to do it. I currently have a pair of white linen trousers that sit too low on the waist for my liking; a silk shirt with the button missing from one cuff; and a Cos pea coat bought new with five buttons, none of which remain.

I suppose I’ve been put off visiting my local tailor by the imagined expense of repairing items and that I am clearly getting along well enough without by wearing jeans and a T-shirt on repeat.

But, finally, I bag the clothes up and take them to the tailor. The man behind the counter is brisk and efficient. I put on the trousers and show him how much higher I would like the waist to be. He puts the pins in the appropriate places, then suggests another amendment to the legs, just below the seat. It’s not something that would have occurred to me, but even just held in place by pins, I can see that he is absolutely right: it brings together the trousers’ new fit, making them coherent as a high-waisted style. This, I realise, is the appeal of going to a tailor: altering clothes to be bespoke, so that they are a pleasure to wear.

In the weeks that follow, I receive compliments on the linen trousers that I never did before – chiefly, of course, because I never used to wear them. But there is no doubt that now, in fitting me precisely, they look more expensive than they were. Yes, at about £35, the cost of having them altered was nearly as much as I paid for them in the first place. But now that they are back in rotation, I see that my apprehensions were rooted in a false economy: there is no item of clothing more costly, to the environment or your bank balance, than the one you never wear.

Elle Hunt