Babies: they are cute and everything, but what are you supposed to do with them all day? It has been a problem for busy parents for millennia. Precious, terrifyingly fragile and capable of wreaking untold carnage, they are profoundly inconducive to adult work. So, the central aim of childcare has long been safe containment.

Historians debate when childhood acquired a distinct status and children were viewed as something other than incompetent mini-adults, but anyone who has ever met a baby knows they are an absolute liability. The rich could hire childcare – wet nurses, nursemaids, even cradle rockers – but we know less about how ordinary people managed.

Unless it ended in tragedy, that is. The historian Barbara Hanawalt analysed medieval English coroners’ rolls, which show that animals, water and especially fire posed a far greater danger then than they do now; a typical accident might involve a pig or a chicken knocking embers from the hearth into a nearby crib.

Swaddling is the age-old, cross-cultural solution to restless infants. There is a woman on TikTok who swaddles stuff (a geriatric Labrador, rescue cats, chickens) and almost every subject seems deeply, physiologically calmed by the process.

In medieval and early modern times, it was more about stopping your infant from getting up to no good. “The stated purpose of swaddling was to mould the infant’s head – to train its limbs and back to grow straight and to protect it from ripping off its ear, gouging out its eyes and whatever other depredations it had in mind,” according to a paper on 19th-century infant containment by Hilary Russell. This might be combined with tying, to stabilise the crib or to restrain its occupant.

There was also a lingering suspicion that infants were a bit … off. “Many Christian writers on infancy seem quite daunted and even frightened by how much an infant resembles an animal – or perhaps the devil – in lack of human skills and selfish and unbridled desires,” says Russell, echoing what many a parent has thought once or twice at 4am. “Swaddling and moulding its limbs must have made it seem more human – a step away from brutish existence and closer to a state of grace.”

But what about when they are too big to swaddle and start grabbing at your pikestaff or your angriest sow? It’s no surprise that crawling was long viewed as bad news – an animalistic practice to be prevented and contained. Long robes helped, while medieval manuscripts depict wheeled walking frames. A childcare manual from 1473, A Regimen for Young Children, suggested: “When children begin to creep around the floor and reach after things, one should make for them a little pen of leather so that they do not hurt themselves.” But once they were walking, all bets were off. Maybe get a few brochures in for the local monastery, just in case?

Time for some pictures of people from history trying to cope with infants without resorting to opium (which they did often); let’s go.

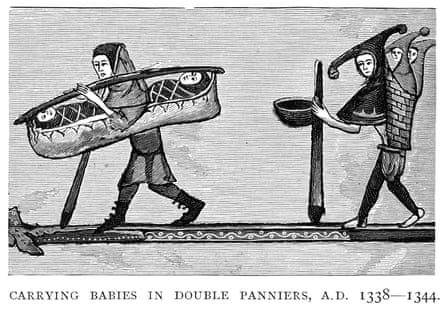

Babies in panniers, 14th century

In humoral medicine – which was popular until the 17th century and held that chemical systems regulated behaviour – babies were considered warm and moist when fresh; handling was to be avoided so they didn’t get misshapen (“like a cookie”, according to the Baby Historian, Aradia Wyndham). Their limbs were bound and they were swaddled; sometimes, they were also attached to a board to keep them nicely shaped, especially in transit. These ones look commendably well wrapped; I reckon you could have popped them in the post if it had existed. The men carrying them look sulky, though; I bet they have complained to their mates about “babysitting” their own children.

Mill girl, circa 1900

Ah yes, an early, deadly incarnation of “bring your daughter to work day”. If you can’t find anyone to look after your toddlers, do not – and I can’t stress this enough – bring them to a textile mill. Another picture from the same North Carolina mill suggests a good chunk of the workforce were under 12, though, so perhaps this tot fitted right in.

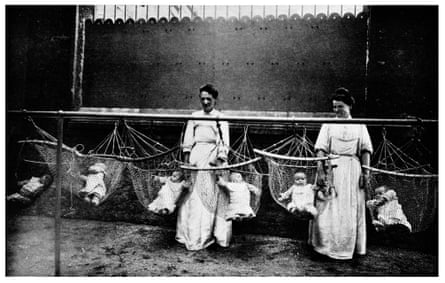

Factory nursery, 1918

Here is a more enlightened solution for working parents: factory nurseries. Thank you, first world war. In 1917, one in three jobs in France were occupied by women; a wave of strikes demanded higher factory salaries, but also workplace creches. The government, desperate for the munitions to keep coming and the economy to keep turning, agreed. The Citroën factory in Paris, which employed 6,000 munitionettes, had already opened one in 1915. Vive la France!

Washing-line babies, 1925

Given the lack of information accompanying this image– other than it was taken in Britain – I suspect it was a cute gimmick, rather than a serious childcare strategy. However, there is evidence of hanging babies safely on hooks, trees or other convenient points, as in an 1850 illustration in the Wellcome Collection.

Sleeping-bag babies, 1930

Look how delighted the nurse in this picture is with her well-trussed charges – and rightly so: they are safe, warm and unable to punch each other. Although these toddlers are apparently in a children’s home in Moscow, 1930s Soviet Russia also encouraged young mothers to use state daycare to get back to work. Propaganda posters suggested babies were bored at home and happier in a creche, or depicted bucolic, sunny scenes of merry outdoor childcare (no sleeping-bag swaddle necessary).

Baby cage, 1937

A patent for a baby cage was filed by an Emma Read in Spokane, Washington, in 1922, but enterprising Eleanor Roosevelt had already built her own from chicken wire in 1906, according to her autobiography. Although baby cages lasted until the 1950s, the craze peaked in the 1930s in London, when they were distributed to members of the Chelsea Baby Club with no access to outdoor space; East Poplar council also proposed introducing them. This was all a plot by big fresh air: “If a baby is to thrive, of course, it must be kept out in the open air and sunshine,” wrote the Richmond Times in 1913 , seemingly confusing babies and geraniums. I would be concerned about pigeons.

David the lobster-pot baby, 1949

“Lobster-pot baby” sounds like a wholesome picture book by John Burningham or the Ahlbergs; I am tracing the storyline out in my head already. The image doesn’t disappoint, either: look at that perfect floral pinny and young David’s pleasingly determined expression, sturdy shoes and tightly grasped biscuit.

Scooter sidecar, 1963

I don’t consider myself particularly hung up on health and safety, but this extremely 1960s picture of Anita White of Teddington, south-west London, and her daughter, also Anita, gives me palpitations. Is mini-Anita secured in any way? There is not even a suspicion of a helmet (which was not obligatory until 1973). There is nothing groovy about a head injury, guys!