The fashion industry is heading for a reality check. By the end of 2024, self-regulation of sustainability may no longer be an option. Many new rules around the world are set to mandate action on everything from textiles production and chemicals use to recycling and waste.

While some industry progress is evident, the pace of transformation falls short of what is needed to prepare for impending regulations. Across the industry, the polluting use of fossil fuels continues to dominate production while circular business models are still in their infancy. If progress continue at the current pace, clothing and footwear consumption is expected to increase by over 60 percent, from 62 million tonnes in 2022 to 102 million tonnes in 2023.

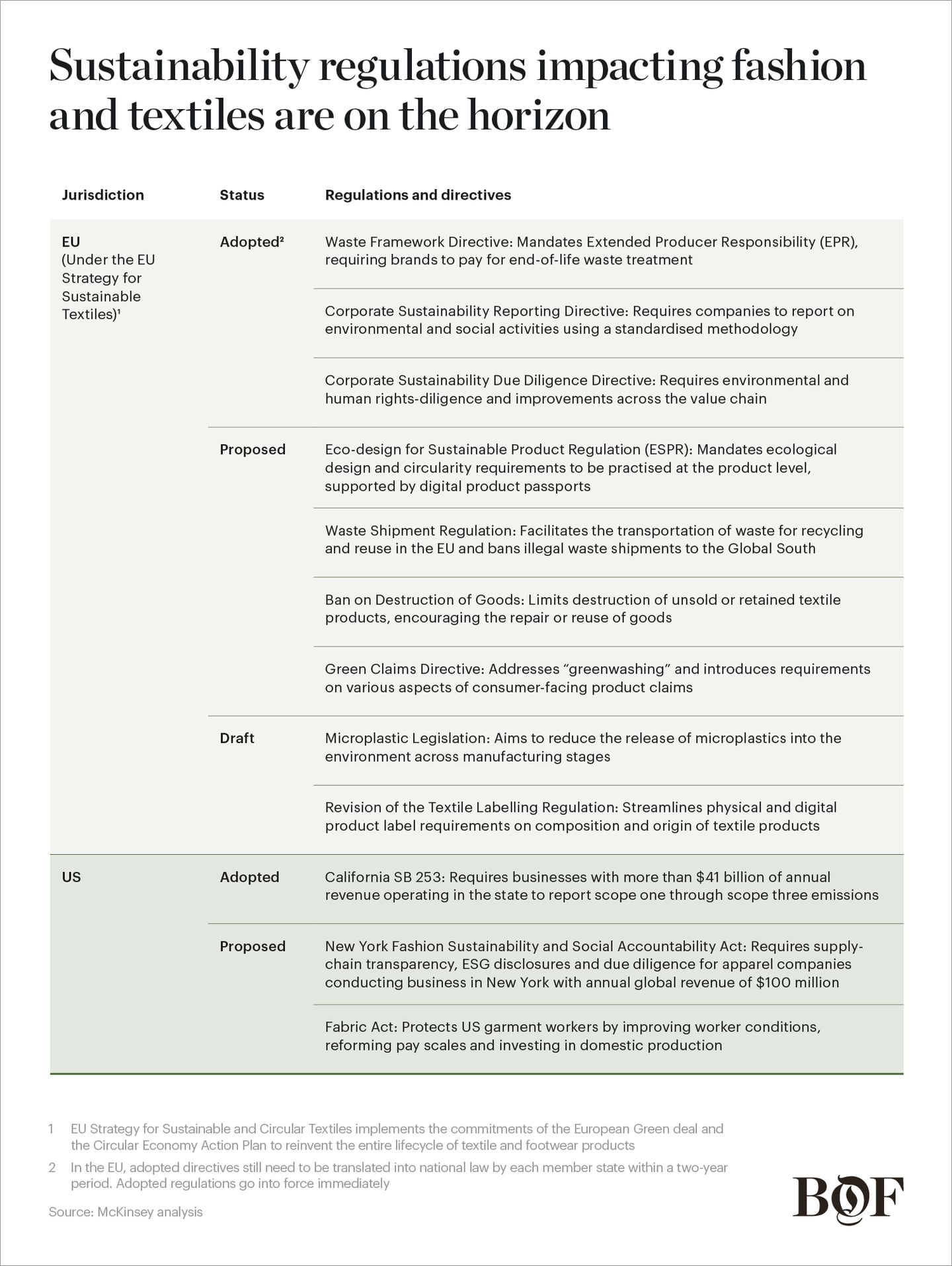

With the industry struggling to move forward, regulators are stepping in. Leading the charge is the EU as it pursues a vision for a climate-neutral, circular economy, with growth decoupled from the consumption of finite resources. The EU’s textiles vision is encapsulated in its Strategy for Sustainable and Circular Textiles, passed in June 2023, which envisages an industry defined by products made with respect for the environment and social rights. As many as 16 pieces of legislation are currently under discussion, with the first coming to force in 2024. The window for brands to prepare to comply is narrowing quickly.

The Heat is On

With fashion responsible for significant emissions, pollution and waste, regulators are set to require companies to both fix their own operations and force higher standards in their supply chains. The regulations apply across key areas of activity, impacting consumers and companies within and outside the EU.

Product design: Up to 80 percent of a product’s environmental impact is determined in the design phase and is baked into materials and dyes. The EU’s flagship Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation (ESPR), set to come into full effect by 2025, sets minimum design standards for all individual products sold within the EU. This includes requirements around recyclability, durability, reusability, repairability and use of hazardous substances. Digital product passports that collect and share this information with consumers are expected to become required by law.

Marketing: Greenwashing is high on consumer and regulatory agendas, with the claims of many companies seen as vague or misleading. The new EU Green Claims Directive curbs greenwashing by requiring sustainability-related declarations and statements to be specific, backed by evidence, verified by independent bodies and communicated clearly. France has already taken the first step, requiring large companies to put carbon labels on all clothing sold in the country.

Waste management: Less than 1 percent of fashion textiles are recycled and a truckload of products are sent to landfill or incinerated somewhere in the world every second. An amendment to the Waste Framework Directive is calling for Extended Producer Responsibility, which already exists in France, and which requires companies to finance the collection, sorting and recycling of textile waste. Fees are expected to vary based on production output and pollution levels caused, a principle known as “eco-modulation.” All EU countries will be required to launch textile collection programmes by 2025 and the destruction of unsold goods is expected to be banned.

Reporting: Despite huge volumes of corporate environment, social and governance (ESG) disclosure, companies still struggle to secure sufficient data and performance metrics or define economic activities that can be considered sustainable. A lack of comparability across brands inhibits effective decision making among investors and consumers. The upcoming Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) requires companies to report on ESG activities via a standardised framework. Meanwhile, the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive mandates environmental and human rights diligence and action plans across the value chain.

Notably, the requirement for standardised, comprehensive public disclosures has become a lightning rod of debate in the fashion industry, with some executives concerned about the amount of data and analysis required. At a recent conference, the head of sustainability at Puma said that the brand had been publishing reports for 20 years but was “nowhere near being able to fulfil the requirements of CSRD.”

The impact of the EU’s new rules are expected to extend beyond the region’s borders, especially into Asia, where 70 percent of the EU’s textiles are manufactured. In addition, lawmakers in other regions are progressing their own initiatives. In the US, the New York Fashion Sustainability and Social Accountability Act plans to hold major brands accountable for ESG impacts and supply-chain traceability. In the UK, the Green Claims Code aims to stem greenwashing, while China has committed to peaking carbon emissions before 2030 and become carbon neutral by 2060.

As the regulatory landscape evolves, the year ahead presents an opportunity for fashion executives to revamp their business models. But this will likely require a holistic approach rather than targeting select parts of the value chain.

Traceability: Achieving full supply-chain visibility across all tiers of manufacturing will be a critical enabler for regulatory compliance. However, many brands currently have limited visibility over their suppliers at best, and therefore lack reliable and standardised data to make meaningful progress. Advances in blockchain and other technologies may enable more transparent and efficient monitoring. Adidas, for example, has achieved material traceability at scale by using TrusTrace’s digital traceability platform, which is also used by companies including Renfro Brands and Brooks Running.

Sourcing and production: As upstream supply-chain activities account for the majority of carbon emissions in apparel, there may be a sharper focus on decarbonising material and garment production. In the production process, main decarbonisation levers include energy efficiency and energy transition initiatives. As brands shift to more sustainable materials, they may look for new suppliers or join strategic alliances. Kering, for example, has established supplier-focused sourcing standards and created the Material Innovation Lab dedicated to the sourcing of sustainable materials and fabrics, while Hermès has partnered with start-up MycoWorks’ to secure access to its engineered mycelium.

Design: New requirements for circularity are expected to shake up the design process. For example, a focus on longevity and durability may demand fresh attention to details such as stitching and seams. Equally, materials that cannot be separated in recycling may need to be avoided, meaning designers may need to think more creatively about design choices. Design libraries may increasingly support material selection, while 3D sampling may reduce use of resources. Packaging design is also impacted, with new rules emerging around composition of labels and tags and elimination of single-use plastics.

End-of-life waste: To minimise production and waste, new business models are coming to the fore. Resale continues to grow through brand partnerships with secondhand marketplaces, such as The RealReal or Vestiaire Collective. In-house programmes offering resale, rental and repair are gaining traction as well. There is also an opportunity to accelerate closed-loop recycling. Stockholm-based Renewcell is ramping up the world’s first at-scale fibre-to-fibre recycling factory. In partnership with global brands like H&M, Inditex and Levi’s, Renewcell plans in 2024 to reach full capacity of 120,000 tonnes, or the equivalent to 600 million T-shirts. Fully embedding these new materials into supply chains remains a challenge, however — Renewcell recently cited slower-than-expected sales of its cellulosic pulp to fibre producers.

This article first appeared in The State of Fashion 2024, an in-depth report on the global fashion industry, co-published by BoF and McKinsey & Company.