On an industrial site near the French-Belgian border, high-end sneakers, handbags and ready-to-wear garments are routinely dismantled, shredded and granulated in preparation for recycling.

None of these products have ever been used by a consumer. Instead they are a small slice of what has become a billion-dollar challenge for luxury’s biggest businesses: what to do with goods that don’t sell from season to season?

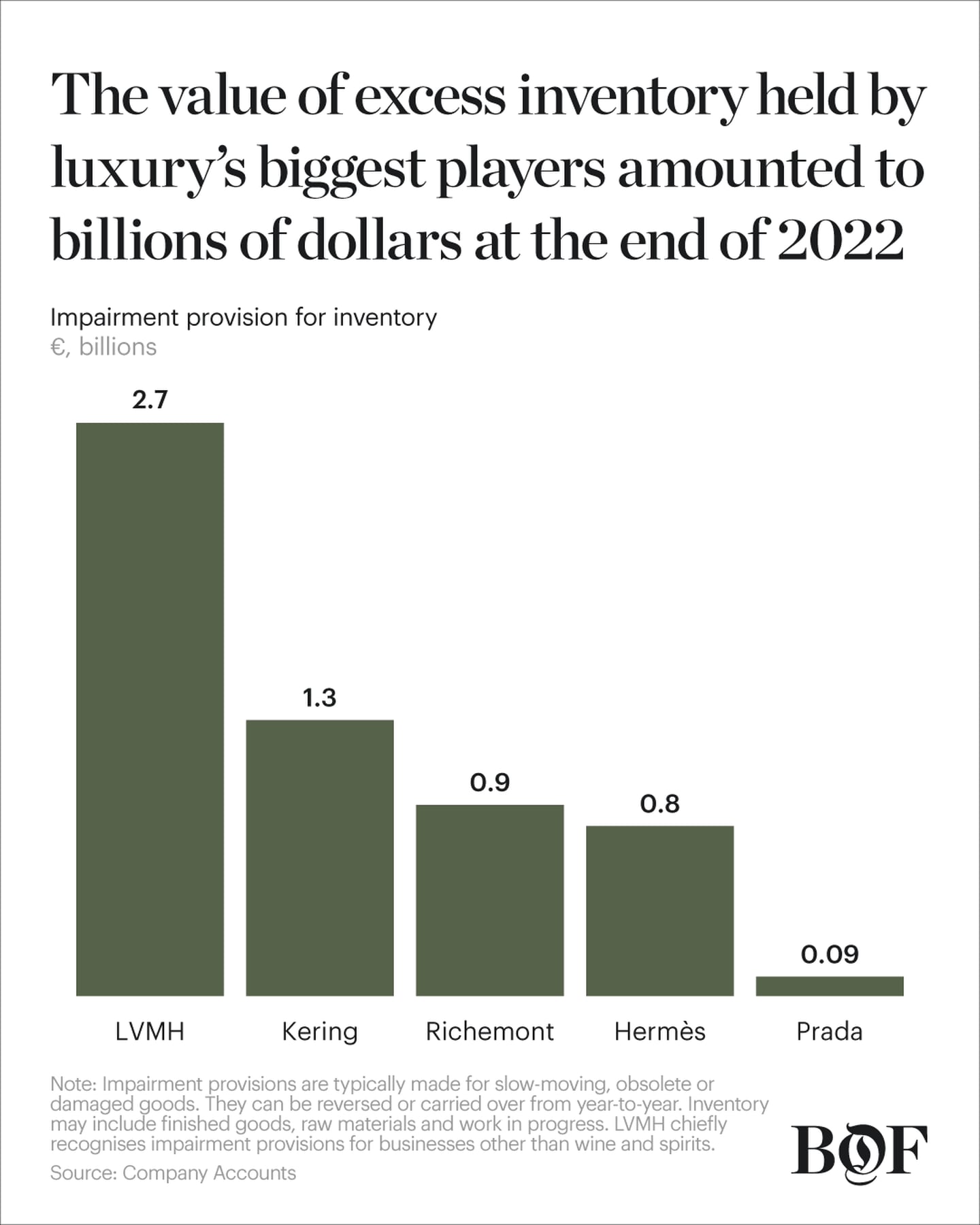

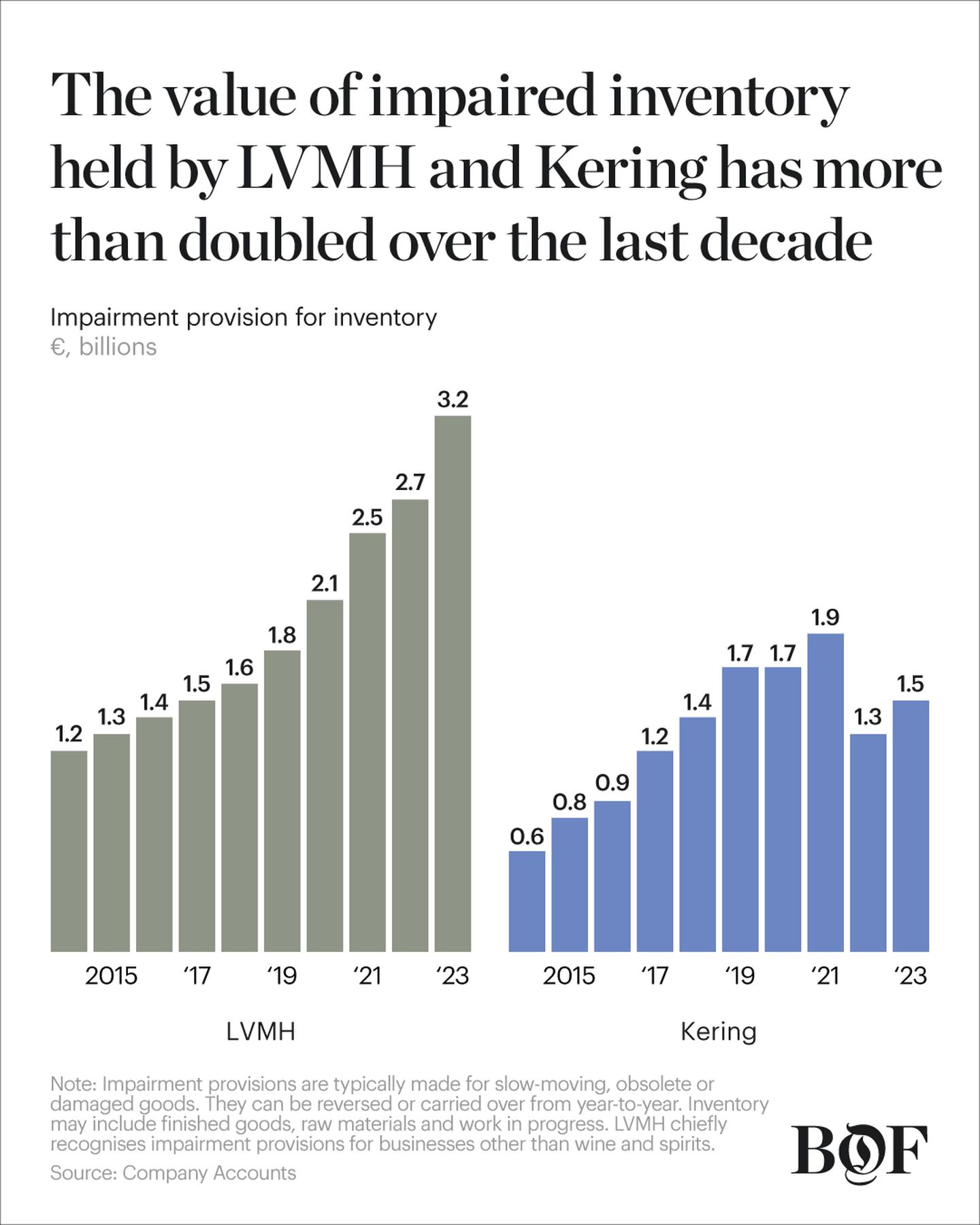

Last year, LVMH held €3.2 billion ($3.5 billion) of stock it had written down because of “obsolescence” or lack of sales prospects, up from €2.7 billion in 2022. Gucci-owner Kering recorded a €1.5 billion allowance for its inventory, an increase from €1.3 billion a year earlier. That’s the equivalent of hundreds of thousands, if not millions or products, though these numbers include raw materials and prototypes as well as finished goods.

Such excess is a feature of fashion’s dominant business model, designed to maximise production efficiency and sales prospects in a trend-driven industry where accurately aligning supply and demand has been a perennial challenge. But how companies handle the growing glut is an increasingly complicated question.

Luxury brands have long used staff sales, private shopping events and outlets to discreetly sell off old stock. What they couldn’t offload, they destroyed to avoid damaging their pricing power and carefully cultivated perception of exclusivity.

But luxury’s relationship with discounters has always been uneasy — even more so now as slowing sales push up excess inventory levels across the sector. Meanwhile, the practice of burning unsold goods has become a reputational and regulatory hazard that’s already been outright banned in France and will be outlawed across all of the EU soon.

Recycling is one solution, but manually dismantling each product so that its constituent parts can be reprocessed into new materials is costly, time consuming and currently limited in scale. Lower-priced brands, like Nike, have faced criticism for shredding brand new products they couldn’t sell in recycling plants.

“It is a big issue for the industry,” said Claudia D’Arpizio, a partner at consultancy Bain & Company. “If you’re a big brand and you have a lot of inventory, it’s very difficult to find a solution at scale. I would say we’re less than 50 percent of the way [there].”

A Culture of Excess

Luxury brands lean into the idea that their products are inherently more sustainable than cheaper labels because they make smaller quantities and design for longevity. But the reality is that they have always over-produced.

Higher volumes mean better economies of scale during manufacturing. And over-ordering is viewed as cheaper than the risk of missing a sale because stock isn’t available. For luxury apparel, a 50 percent full-price sell-through rate is considered good, according to analysts.

“There is embedded excess in the system,” said D’Arpizio. “Fashion will never have zero leftovers; this is structural.”

As luxury’s biggest players have grown over the last decade, so has the value of their overstock. The cost of impaired inventory held by Kering and LVMH more than doubled between 2014 and 2023.

To be sure, gauging the true scale of the issue is tricky. Provisions can be reversed or carried over from year-to-year. Companies don’t disclose details about the volume of products they expect to make a loss on, or what they do with this stock. Luxury trade groups have pushed back against regulation that could require them to do so.

The wide array of products that can be included in these numbers makes analysis and comparisons across companies trickier still. For instance, LVMH’s inventory includes stocks of make-up, perfume, fashion, jewellery and leather goods, as well as the raw materials used to make them. (Wine and spirits are largely excluded from inventory provisions, according to the company’s accounts.) By contrast, Kering’s brands have a stronger focus on ready-to-wear, which has a much worse sell-through rate than more trans-seasonal products like leather goods.

Investors are conditioned to tolerate such waste so long as it doesn’t hurt the bottom line. The value of LVMH’s impaired inventory amounted to just 4 percent of revenue in 2023. The company said products it has written down are still likely to sell during this financial year. Kering’s excess inventory amounted to a larger 8 percent of sales, but that reflects its focus on fast-moving fashion products, analysts said. The company did not provide comment.

A Luxury Problem

In the summer of 2018, Burberry published a routine set of financials containing a figure that would prove explosive: the British luxury house had burned nearly $40 million-worth of goods in the preceding financial year.

The practice was commonplace across the luxury sector at the time, though most companies didn’t talk about it publicly. Burberry had published the figures for years without remark. But something in the zeitgeist had shifted that year, with environmental concerns moving up the agenda and investors questioning how such waste reflected on the British brand’s sluggish turnaround effort. The backlash came swiftly and within months the company had vowed to stop destroying unsold stock.

It took regulators stepping in for other brands to follow suit. Kering announced plans to stop destroying any unsold products globally from 2022, after France passed a law that would ban the practice. Hermès said in its last annual report that the company no longer destroys unsold items in France and will extend this policy to operations around the world between 2025 and 2030.

Large luxury companies are still trying to figure out what to do instead. Of course, lower-cost brands over-produce too, but unlike luxury players, mass fashion businesses are less squeamish about resorting to steep discounts, cut-price retailers and bulk traders.

“This is only pertinent really to luxury; the rest of these brands aren’t that pristine,” said Ken Pucker, a senior lecturer at the Tufts Fletcher School and former chief operating officer at Timberland.

AI, Outlets and Recycling

Luxury is trying to adapt, starting with design and production planning.

Kering has turned to artificial intelligence in a bid to help improve sales forecasts and limit the quantity of unsold goods at the end of each season. It’s succeeded in improving the accuracy of its inventory predictions by upwards of 20 percent, and the results are still getting better, it told The Business of Fashion last year. LVMH entered a partnership with Google in 2021 with a similar goal to improve demand forecasting and inventory optimisation.

“It’s become very important … to adapt production to the level of demand because dealing with leftovers is quite a sensitive topic,” said Charles-Louis Scotti, head of luxury goods research at financial services firm Kepler Chevreux. Large luxury brands “now have super-efficient warehouse centres and can reallocate inventory anywhere in the world, so if demand collapses in Europe they can ship to where demand is still very big.”

But accurately aligning supply and demand remains highly challenging, so luxury brands are also forging relationships with charities and schools to donate and upcycle leftover products. And they’re still discounting, even when they say they aren’t. Top-end brands like Louis Vuitton, Hermès and Chanel host sales for staff, friends and family that can shift significant volumes. Hermès reportedly generates more than €100 million every year from such events. Prada said the company disposes of all its overstock through private sales and outlets.

The off-price sector is booming, boosted by a glut of inventory and rising prices that are pushing consumers to look for deals. In Europe, the segment’s sales amounted to €40 billion in 2021, according to consultancy McKinsey & Co, or 11 percent of the total fashion market. It is expected to grow at five times the rate of full-price sales in the five years to 2030. Today, 13 percent of all luxury goods by value are sold through off-price outlets, according to Bain.

“Outlets will always play a strategic role because there’s always a need for seasonal products,” said D’Arpizio. “It’s a strategic channel.”

But with the value of excess inventory reaching into the billions at some companies, luxury brands are looking for other ways to manage stock without flooding the market. “In the end, the sheer amount of products being created is in a way too much to claim in sales and outlets,” said Francois Souchet, a circular economy and sustainability strategist.

Increasingly, companies are looking at ways to repurpose what they cannot sell. Gucci has worked with a collection of designers, brands and artists on its Continuum project, which incorporates past pieces into new products. LVMH showed a collection in December created by artistic director Kevin Germanier using unsold products and excess fabrics from the group’s maisons.

Both companies are exploring opportunities in recycling, too. LVMH launched a circularity initiative late last year, bringing together different start-ups and industrial partners the company has been working with in the space.

Kering has said all of its brands have developed pilot projects with Revalorem, the company that operates the processing site near France’s border with Belgium. The luxury group discretely invested in the business last year, according to a December presentation.

But the biggest lever for change is not producing too much to begin with. “Eliminating the need to think about unsold products in the first place is the vital starting point,” said Elisa Niemtzow, vice president for consumer sectors at consultancy BSR. “It’s going to take creative and innovative thinking — and maybe thinking about different models of doing business.”