Chanel Scales spent three years dreaming up window displays for a global fast-fashion retailer’s stores across the Midwest. She hoped her skillful styling of mannequins and clothing-and-accessories setups would someday lead to a corporate job where she could set the visual strategy for the chain’s locations nationwide.

But, every time she tried to make the leap, she hit a dead end.

“I’d have meetings with my store manager to let them know ‘I’ve been at the store level for a while and I would like to move up,” she said. “Nothing ever really came from it.”

Scales quit seven years ago, and is now a clothing designer. Over the years, she’s heard from former colleagues who stuck it out longer, only to eventually share her disillusionment about ever advancing into a corporate career.

The post-pandemic labour shortage has forced retailers to get serious about improving working conditions in stores. Companies have raised pay, expanded benefits and rebranded sales associates as brand ambassadors and style advisors.

Most of these measures are designed to convince store employees to stay in their roles longer. But though many companies talk up training programmes and tuition assistance designed to give low-level workers a leg up on the corporate ladder, many retail employees who spoke with The Business of Fashion say they see no viable path from their stores to headquarters.

Historically, that wasn’t the case. While never an easy transition, the fashion industry is full of executives who got their start selling shoes, stocking shelves or building window displays. Today, more corporate roles, even at the entry level, require advanced degrees and specialised skills that aren’t easily obtained while ringing up customers — more supply chain experts and digital marketers, fewer buyers and merchandisers.

But fashion companies overlook what their sales associates could bring to the table at their own risk. Retail’s frontline workers directly handle customer issues, manage merchandise returns, and see firsthand what resonates with shoppers. Their feedback can be crucial to shaping corporate strategy and driving revenue growth. What’s more, retail’s corporate ranks are predominantly white men but its stores are far more diverse when it comes to age, gender, and race.

“The store staff is extremely close to the customer and the consumer experience — getting them in corporate is going to help you become more customer-centred in your strategies,” said Kyle Rudy, a senior client partner at Kirk Palmer Associates.

On the Front Lines

Often, training programmes run by brands and retailers cater to recent college graduates and other professionals looking to transition into the sector. They offer a crash course in areas like fashion merchandising, inventory and customer experience. Other programmes, such as the National Retail Federation’s Rise Up, offer training (to anyone looking to break into the retail industry) in areas such as marketing and logistics, but doesn’t guarantee a corporate job at the end.

A few companies specifically target the store-to-corporate pipeline. Vans and Timberland parent VF Corp. launched Powering Potential in 2021. The programme provides training, mentorship — and a guaranteed job in areas like marketing, product and merchandising — for store associates who participate.

Powering Potential serves multiple purposes: attracting and retaining store associates who want to transition into corporate roles, but also helping VF gather more firsthand intel on its customer needs and diversify its corporate talent pool, said Lauren Guthrie, VF’s vice president of global IDEA & talent development. (IDEA stands for Inclusion, Diversity, Equity & Action.)

“Our richest diversity is in our retail stores — and that’s not just demographic diversity, but cognitive and experiential diversity, too,” Guthrie said.

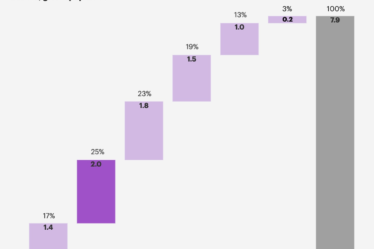

To date, Powering Potential has graduated 21 employees, with two thirds moving into permanent corporate positions. Those who opted out often did so because they weren’t able to relocate to the company’s headquarters in Denver, Guthrie said.

Among its success stories is a sales associate who accepted an apprenticeship with Vans. During the programme, she helped the brand’s women’s skate team identify and correct some of its blindspots when it comes to marketing to women in stores. She landed a full-time role with the same team.

“We’ve had a few retail apprentices who’ve come in with bones to pick and rightfully so — they’ve been at the end of the line where things aren’t connecting or resonating or where they feel we’re lacking in authenticity,” Guthrie said.

Rebuilding the Pipeline

The best retailers have integrated the notion of developing store talent into their “larger talent vision,” Guthrie said.

Most fashion firms will need to hone in on the kinds of corporate roles where store sales teams can offer the most value and have the smoothest transition, Rudy said. Often, though not always, that means marketing, e-commerce and merchandising, he said.

Companies also need to set realistic expectations. Though her managers may have indicated otherwise, Scales’ visual merchandising role was never likely to lead to a corporate job, as even at the highest level it’s usually a hands-on position, said Liza Amlani, principal and co-founder of Retail Strategy Group, an advisory.

“To transition to corporate, companies are looking for more of that selling experience — the ability to work with numbers and data,” Amlani said.

Ensuring that there are enough viable opportunities for retail associates is part of the reason VF has kept the number of apprentices it accepts relatively low, Guthrie said.

“We’re being cautious because the last thing we want to do is bring folks in that we don’t have the potential of converting to full time roles at the end,” she said.

Even in the post-pandemic work-from-home era, most corporate roles will require relocation to the company’s headquarters or frequent travel to and from other corporate sites, Rudy said. So if companies aren’t willing to be flexible in this regard, they should be upfront with candidates and also recognise that their store-to-corporate pipeline may remain weaker in stores farther from the headquarters.

Whatever the tinkering required to pull these programmes together, the results are worthwhile, Guthrie said.

“We’re all trying to figure out the right way of motivating, inspiring, advancing our talent … and it requires vision and certainly investment to make programmes like this real,” she said. “But, for us, it’s a massive opportunity to do more. We’ve scratched the tip of the iceberg.”