THE Unstoppables

At 87, the actor and writer says performing and activism remain his driving forces.

The Unstoppables is a series about people whose ambition is undimmed by time. Below, George Takei explains, in his own words, what continues to motivate him.

I was born April 20 of 1937. Pearl Harbor was bombed on Dec. 7, 1941. I had turned 5 by the time a morning arrived that I can never forget. Two months after Pearl Harbor, in February 1942, Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, decreeing that all Japanese Americans — 125,000 of us by the latest count — on the West Coast were to be imprisoned with no charge, no trial and no due process, only because of how we looked.

A few months after the order was issued, we saw two soldiers marching up our driveway in Los Angeles carrying rifles and shiny bayonets. They banged on our door with their fists and one said, “Get your family out of this house.”

At the time Henry was 4, I was 5 and my baby sister was not yet 1. My father had had the foresight to prepare a box of underwear tied with twine for each of us. He had two heavy suitcases ready. We followed him out and stood in the driveway while our mother came out escorted by another soldier, my baby sister in one arm, and carrying a duffel bag. That terrifying morning, burned into my memory, is what led to me becoming an activist.

Before we were interned, my father had a successful dry-cleaning business on Wilshire Boulevard, right by Bullocks Wilshire, the most fashionable department store in Los Angeles. By the time the war ended, we had nothing. Given a one-way ticket to anywhere in the United States and $25 to start over from scratch, we returned to Los Angeles, where my father’s first job was as a dishwasher in Chinatown. Only other Asians would hire us.

I wanted to be an actor — it was my passion. I enrolled at U.C.L.A., and while I was there, a casting director plucked me out and put me in my first feature film, “Ice Palace,” with Richard Burton and Robert Ryan. From there I did “Hawaiian Eye” and “My Three Sons,” and I became this unlikely success, an Asian American doing movies and TV. Then I was cast in “Star Trek,” which gave me a platform very few people are given. And I continue to use it. Last year began with a five-month stay in London, where we took a musical I’d begun developing about the internment years earlier.

-

1968

Mr. Takei played Lt. Hikaru Sulu on “Star Trek: The Original Series.”

CBS, via Getty Images

-

1968

Mr. Takei with John Wayne in “The Green Berets.”

Silver Screen Collection, via Getty Images

-

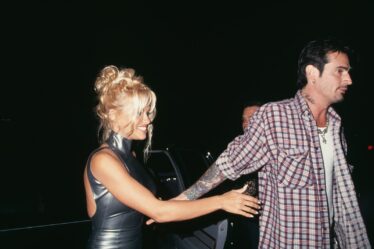

1994Mr. Takei promoting his book “To the Stars.”

Bill Tompkins/Getty Images

-

2008

Mr. Takei married Brad Altman in Los Angeles.

Stan Honda/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

-

2012

Mr. Takei, a former Boy Scout, in New York City’s pride parade.

Timothy A. Clary/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

-

2023Curtain call during “George Takei’s Allegiance” in London.

David M. Benett and Alan Chapman/Getty Images

My father suffered terribly in the camps, yet he continued to believe deeply in democracy. He was an unusual Japanese American of his generation in that most of the interned parents were too pained by the experience to talk about it openly. My father continued to discuss it and loved quoting Lincoln’s lines from the Gettysburg Address about this being a government of the people, by the people and for the people.

That’s what inspires me. It’s the people that make a democracy work, and, sadly, most people are not equipped anymore to take on the responsibility of being American citizens.

Current and upcoming projects: Appeared in 103 performances of the British production of “George Takei’s Allegiance” at Charing Cross Theater; voiced the character of Seki in the Netflix animated series “Blue Eye Samurai.” A new picture book, “My Lost Freedom: A Japanese American World War II Story,” was released April 16, and he will appear as Koh the Face Stealer in the Netflix series “Avatar: The Last Airbender.”

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

The Unstoppables is a series about people whose ambition is undimmed by time. Below, the writer Maxine Hong Kingston explains, in her own words, what continues to motivate her.

In a way, I don’t believe in old age. I hear people say, “this hurts” or “that hurts,” and they attribute that pain to old age. It’s not age. Age is just time going by, and that’s very mysterious.

I don’t think about vanity much. I look in the mirror, and if I think, “I look young,” that’s good enough.” Instead of wearing lipstick or rouge, I darken my eyebrows. I can express all kinds of things just with my eyebrows.

I do think about retiring, but stories and ideas keep coming. As Phyllis Hoge, a poet and my best friend, used to say, “We won’t die until we’ve finished our work.”

I was born this way. From a very young age I just wanted to be a storyteller or a poet. I didn’t know what I was going to write. I wasn’t even aware at that age that I had nothing to write about.

Sometimes I’ve thought, or had the illusion, that I’ve been this way for two incarnations back. This is my third reincarnation as a writer. John Whalen-Bridge, who is writing my biography, is thinking of calling it “American Bodhisattva.” I don’t go around thinking I’m a bodhisattva, but I suspect that younger women see me in that way, as somebody who could help them, have mercy on them. That’s the impact I’m having on young people. I just play the role of grandma for them.

I’m not nostalgic myself. I don’t like the feeling of nostalgia. Nostalgia has something to do with regret, the sadness of “Oh, this time is over.”

I don’t like it when I have that feeling, but I don’t seem to get it very often. I like to go into the new.

Current and upcoming projects: Second edition of “Veterans of War, Veterans of Peace,” a compilation of storytelling and poetry by wartime survivors, with new contributions by Israelis and Palestinians; revising (“polishing,” in her telling) a diary of the past decade.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

I love writing, I love acting, going onstage and doing my little one-woman show, and I refuse to be defined by a number, by an age. I think that’s terribly old-fashioned and not relevant in today’s world.

But you have to be resilient in this business. Rejection is a part of it. I look with dismay at so many of my fellow actors, fallen by the way because of drink and drugs. My father — he was a theatrical agent — instilled in me that I should develop skin like a rhinoceros, and be like a marshmallow on the inside.

-

1952

Ms. Collins in “I Believe in You.”

Hulton Archive, via Getty Images

-

1955

“Land of the Pharaohs,” directed by Howard Hawks.

Film Publicity Archive/United Archives, via Getty Images

-

1977

Starring in the science fiction film “Empire of the Ants, based on a short story by H.G. Wells.

Eddie Sanderson/Getty Images

-

1981 The TV series “Dynasty” made Ms. Collins a household name.

ABC Photo Archives, via Getty Images

-

1983 Ms. Collins won the Golden Globe for Best Actress in a Drama Series for her role in “Dynasty.”

Ron Galella Collection, via Getty Images

-

1992

On Broadway in “Private Lives.”

Maria R. Bastone/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

-

2010

In her one woman show, “One Night With Joan, where she shared stories from her life and career.

Walter McBride/Corbis, via Getty Images

-

2017

At the premiere for the film “The Time of Their Lives.”

Walter McBride/Corbis, via Getty Images

-

2024

Ms. Collins was a presenter at the Emmy Awards.

Mario Anzuoni/Reuters

You also need patience. This business is a waiting game. For example, a script was written for me about the Duchess of Windsor [Wallis Simpson]. I’ve been wanting to do it since the 1980s. We got a green light only a month ago. Years ago I thought it would be wonderful to do a picture about growing up with my sister, Jackie. It just hasn’t come off.

It would be set when we were children, during the Blitz. At the time I didn’t feel fear. I didn’t know about the bombings. We would pick up shrapnel in the streets, and in the evening I would put it in my cigar box. We would draw silly pictures of Hitler. We were evacuated 10 or 12 times. We would be in the tube stations, and people would be playing their harmonicas and singing.

A question I’m often asked is, “Why are you still working?” It’s such a fatuous thing to say. I keep on working because I love being busy. It’s tiring when I do my one-woman show, going to a new hotel every night. But it’s rewarding. The audience is so responsive. That buoys me.

Current and upcoming projects: “Behind the Shoulder Pads, Tales I Tell My Friends,” a memoir; “Joan Collins Unscripted,” a British theatrical tour.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

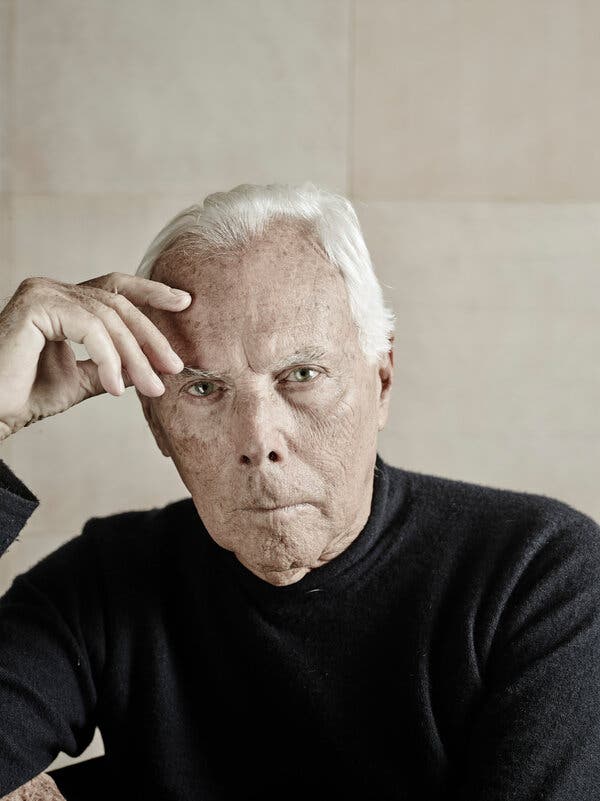

For those of us who grew up in the shadow of war, ambition was something natural, a vital drive. It was not so much a desire for fame and notoriety but rather an urge for personal fulfillment, a way to assert oneself outside the hardship and to overcome it. My mother and father taught me the value of commitment and hard work to get things done. It is a lesson that has never left me.

It took me some time to find my way. First, I studied medicine, then came La Rinascente [an Italian department store, where Armani worked in display] and Cerruti — fashion, in other words. That was the moment when I found my ambition, when I discovered the power of clothes not only to change the way you look but, more profoundly, to influence the way you are and behave.

-

Looks from Giorgio Armani Privè’s couture spring 2024 collection, shown in Paris in January. →

Giorgio Armani Privé

-

Giorgio Armani Privé

-

Giorgio Armani Privé

-

Giorgio Armani Privé

-

Giorgio Armani Privé

-

Giorgio Armani Privé

-

Giorgio Armani Privé

-

Giorgio Armani Privé

-

Giorgio Armani Privé

-

Giorgio Armani Privé

-

Giorgio Armani Privé

I think the challenges — or problems — and the rewards of staying in the game go hand in hand if you do this work for as long as I have and if you remain present. The main pressure is staying relevant without giving in to the pressures of the moment, which often feel very urgent but are forgettable in the long run.

In truth, I don’t think about age much. In my head, I am the same age I was when I started Giorgio Armani. Situations and people change, but the challenges and problems are all the same in the end. My way of tackling them hasn’t changed — with great determination. Audiences evolve, however, and this cannot be underestimated. Stylistic coherence, therefore, must be elastic. Otherwise one becomes rigid. The ultimate gratification is to become a classic — outside of and above fashion — and to be identified with a style.

Current and upcoming projects: Designed 14 men’s, women’s and haute couture collections in 2023.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Being raised during the Depression, we all learned to be creative with what we had on hand. At Christmas or on my birthday, I always got art supplies, and I was jealous that my siblings got bikes and stuff. I realize now that my parents were fostering my creativity.

An early influence on my becoming an artist was Simon Rodia. My grandmother lived in Watts, and we would walk by the Watts Towers when they were being built. I was fascinated by how he used bottle caps and corn cobs and broken plates — trash, essentially — to make art, to make something beautiful. Then, much later, in the 1960s, I saw the work of Joseph Cornell. He refined the use of found objects and materials and boxes, and I thought, “Wow, I’ve kind of been doing that, too.” I didn’t know it was called assemblage, but it made sense to me and set me in that direction as an artist.

The main challenge, I guess, to being an artist is how to make a living. But being a creative person means you have to find ways to do this. I studied design at U.C.L.A., and after I graduated, I made greeting cards, I made jewelry, I got into printmaking and then sold my prints. I taught art classes in colleges all over the states. My creativity kept evolving with my needs as I got married and bought a house, had my daughters and put them through college. Through it all, I loved making art. It kept me going.

I still want to make art. Sometimes in the morning when I wake up, it’s hard to get out of bed, hard to get back into my body and get it to move. But I do it. Not everyone has a reason to get out of bed, something they love to do and that gives their life meaning. I am so lucky that I have that as part of my life. I don’t really think about my age, unless someone mentions it, though I guess I feel middle-aged — which for me is, like, 50 to 70. It would be kind of neat to live to 100, to have 100 revolutions around the sun. I’m pretty close.

-

Greeting Card #8

via Betye Saar and Roberts Projects

-

The inside of Greeting Card #8

Betye Saar, via Roberts Projects; Photo by Paul Salveson

-

Greeting Card #1

Betye Saar, via Roberts Projects; Photo by Paul Salveson

-

The inside of Greeting Card #1

Betye Saar, via Roberts Projects; Photo by Paul Salveson

-

Memories Lost at Sea, 2024

Betye Saar, via Roberts Projects; Photo by Paul Salveson

-

The exterior of Memories Lost at Sea, 2024.

Betye Saar, via Roberts Projects; Photo by Paul Salveson

-

A Different Destiny, 2024

Betye Saar, via Roberts Projects; Photo by Paul Salveson

-

The exterior A Different Destiny, 2024.

Betye Saar, via Roberts Projects; Photo by Paul Salveson

-

Dark Passage 2024

Betye Saar, via Roberts Projects; Photo by Paul Salveson

-

The exterior of Dark Passage 2024.

Betye Saar, via Roberts Projects; Photo by Paul Salveson

-

Drifting Toward Twilight, 2023 (installation view)

Betye Saar, via The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens; Photo by Joshua White

Current and upcoming projects: Completed “Drifting Toward Twilight,” an installation at the Huntington in San Marino, Calif.; “Betye Saar: Heart of a Wanderer” exhibition at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston; “Betye Saar: Serious Moonlight” at the Kunstmuseum in Lucerne, Switzerland; and completed a newly commissioned artwork for “Paraventi; Folding Screens from the 17th to the 21st Century” at the Fondazione Prada in Milan.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

This year I made time to grow the best vegetables, monster vegetables, that I’ve ever grown in my life. My houses are never done. And I’m writing my autobiography. That’s the scariest project for me because I don’t really like everything about myself — where I’ve been, what I’ve done.

I get up at 6:30 every morning. My housekeeper comes at 7, and I can’t be in bed when she arrives. That would be very embarrassing. I’m a bad sleeper, in any case. At times I’d rather watch a documentary. Other times, I might be anxious, not for me but for my grandchildren. If I wake in the night, I read the headlines to make sure we’re not being bombed.

-

1976Ms. Stewart chopping vegetables in her kitchen.

Susan Wood/Getty Images

-

1980At their Connecticut home, with her then-husband, Andy Stewart.

Arthur Schatz/Getty Images

-

1982Her first book, “Entertaining,” is published.

Patricia Wall/The New York Times

-

1997On “The Tonight Show With Jay Leno.”

Margaret Norton/NBCU Photo Bank, via Getty Images

-

2002Ms. Stewart’s merchandise on display at K-Mart.

Carlos Osorio/Associated Press

-

2004After being sentenced to federal prison for insider trading.

Mario Tama/Getty Images

-

2005

Ms. Stewart appealed her conviction and was released.

Mario Tama/Getty Images

-

2005

Speaking to the staff of her magazine Martha Stewart Living.

Timothy A. Clary/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

-

2015

Ms. Stewart’s friendship with Snoop Dogg has endured for over a decade, leading to several jobs together, including co-hosting a cooking show.

Christopher Polk/Getty Images

-

2020Ms. Stewart founded a new line of CBD products.

Celeste Sloman for The New York Times

-

2023Showing off her cover of Sports Illustrated’s swimsuit edition.

Noam Galai/Getty Images

Maybe a little uncertainty can help fuel ambition. When I left my job on Wall Street, I knew I had to create a career for myself. I became a caterer, catering parties every night. Still I thought, “Will there come a time when my granddaughter — she’s 12 — is asked, “What did grandma do?” And all she can say is “Oh, she made parties for people.” I thought, “I have to do something more than this.” That was in the 1980s, when I wrote my first book, the one on entertaining.

At that time I wasn’t keeping my eye on the home, even though I was known as a homemaker. It wasn’t enough for a marriage. Maybe I regret not having had more children. Maybe I regret that my marriage ended abruptly. We’d been together 27 years. That used to be considered a long time, so when a long marriage ended, it was like somebody died. Maybe I would have liked getting married again. I didn’t, but I don’t mind. Still, I’m curious about what could have been.

My never-ending curiosity drives me. Will it stop? That’s never even occurred to me.

Current and upcoming projects: Autobiography in progress; an untitled Martha Stewart documentary from R.J. Cutler, who directed “The September Issue,” to stream on Netflix in 2024; a PBS documentary series, “Hope In the Water,” set for broadcast in 2024; a partnership with Samsung for a 2023-2024 advertising campaign; a line of gardening clothes and accessories in collaboration with French Dressing Jeans and Marquee Brands.

This interview has been edited and condensed.