PARIS — There was a moment when men’s ready-to-wear was a kind of laboratory for everything exciting happening in fashion. This was particularly true in Paris. But the men’s fashion week that ended here on Sunday night was not that. Instead we got auteurs on autopilot. But what did leave an impression was the sheer scale of it all.

Huge shows have long been the norm at Louis Vuitton, the world’s largest luxury brand, but Pharrell Williams has taken things to another level. This time around his super-sized outing — set in the giant courtyard of the UNESCO headquarters — had a “We Are the World” theme, complete with outfits whose colours matched the skin tones of the models. But in fashion terms, there was nothing groundbreaking going on. The black section that opened the show featured flared tailoring that was sharp, but Pharrell soon reverted to the bling-bling this is his idea of luxury. No matter how flashy the clothes were, the show’s real stars were the bags — Vuitton’s core business, after all — with the rainbow damier the season’s forte.

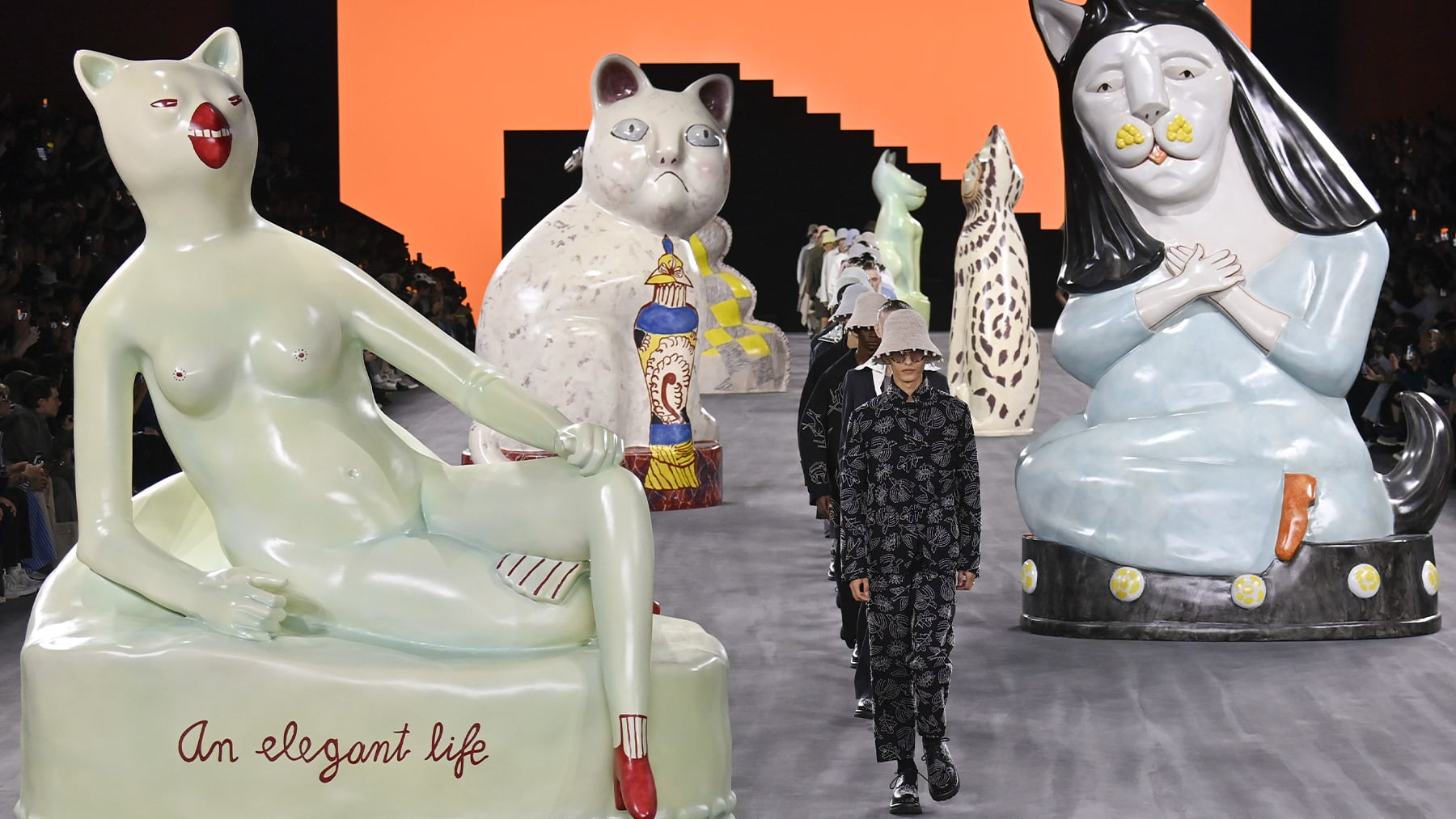

Over at Dior Homme, the gigantic cats on the runway, inspired by South African ceramicist Hylton Nel, were certainly fun to look at, but they also somehow overshadowed one of Kim Jones’ most convincing outings, marked by a sense of sartorial slouchiness and an idea of uniform dressing twisted with deliberate childishness (Hylton Nel animal motifs appeared on jumpers, jackets and accessories) that although Prada-esque in feel (sailor collars and straw bucket hats lined with charms, anyone?), still came across as personal and uncontrived.

The sense of scale was also huge at Amiri, which took over a large chunk of the Jardin des Plantes. But the live jazz band gave the proceedings a more intimate feeling that perfectly matched the charmingly camp and easy formality of the clothes. In the short span of a few years, designer Mike Amiri has turned his namesake brand into a fashion force, keeping its Los Angeles spirit but ditching the city’s laissez-faire mannerism to captivating results.

In a season of hugeness, it was Rick Owens who delivered the ultimate commentary on scale. Is a sense of tribe-building what really makes fashion tick at the moment? Here you had it, grown to grotesque proportions. Owens took over the Palais de Tokyo with a lavish production worthy of a Cecil B. DeMille movie, showing 10 looks, each on a phalanx of 20 beautiful freaks of all sizes and ages who, together, formed a white-uniformed army of love. It was a visual blast that left one ruminating. Owens’ uniforms, like all uniforms, both erased and highlighted the individual identity of the wearer. There was also a sense of massification, driven by faith in an aesthetic credo. The spectacle probably distracted from the beauty of the clothes, but it was timely and joyous.

Scale has been on the mind of Loewe designer Jonathan Anderson for a few years now. This season, however, the goings got such a blast of restraint, stripped-down-to-the-essence, that one could feel erotic tension all around, and all the better for that. For a start there was the set: vast in size, intimate and sparsely-laid in furnishing, it contained notable specimens from Anderson’s own art collection, including works by Carlo Scarpa, Peter Hujar, Charles Rennie Mackintosh. A chair and a coat stand, from a distance, might look like a building, and that was the effect Anderson was after. As for the fashion, Anderson took all the theatrics away to focus on something at once old-fashioned and progressive as silhouette, delivering an unremittingly vertical, graphic statement, complete with lanky physicality, that was a punch. The feathered masks were probably a little distracting and too conceptual, but the focus on outline and surface treatment was magnetic: more proof that Anderson is the big designer with the fiercest experimental spirit of his generation. Now that it’s head-hunting season, he deserves to be considered for an even bigger house where his ideas could flourish further.

Of course, there are auteurs whose work remains under the radar. Hed Mayner is one. The designer was an early champion of gigantic tailoring, and a master of colour and texture. His approach is almost abstract in intention, but his deep understanding of the human body makes for items that are rough and real as well as enveloping and poetic. Best, this season, was the gardening-themed outerwear, the backswept collarless jackets, and most of all the crinkled yet firm tailoring hinting at new ways of dealing with volume. Louis Gabriel Nouchi keeps fine-tuning his literature-drenched, intensely sensual vision, focusing on cut and construction with seductive results. Walter Van Beirendonck is a mainstay in his own garish and playful niche, but his ever-evolving take on cartoonish shape deserves wider recognition.

Junichi Abe of Kolor is another name worthy of bigger exposure. A constructivist with a painterly sense of colour and a wonderful way with slouchiness, Abe has been a fixture of the Paris calendar for a long while. But over the past few seasons his work has reached a striking level of lightness. This season everything was extra light and poetic. Chitose Abe, who is Junichi’s wife and the mastermind of Sacai, has a similar vision, but her work has a taut, sculptural and urban toughness all her own. There was something slightly 1950s to the endeavour this time — think James Dean in “Rebel Without a Cause” — but her ever-abstract approach kept things fresh. Things were not particularly fresh at Kenzo, where Nigo continues to search for the keys to unlock the house’s code and make it modern.

With grandness ruling the fashion scene, designers going for something smaller, closer to real life, made an impact this season. Lemaire shows are always tranches de vie filled with desirable clothes, but since designers Christophe Lemaire and Sarah-Linh Tran moved their showspace to the label’s headquarters in the Marais they have found a groove that, this season, resulted in a collection that was one of their best in recent times.

Auralee, the brainchild of Ryota Iwa, is all about an eerie, poetic brand of twisted classicism. Through timeless, almost undesigned pieces that seem to have sat in the closet forever, Iwa is capable of evoking real feeling, which is a real accomplishment. The hours between work and leisure were on his mind this season, making for a classy collection that had a Saturday morning feeling to it, evoking strollers in the park dressed for both otium and negotium.

Grace Wales Bonner has grown past the preciousness of her beginnings and, again this season, she translated her tailoring finesse and love for beautiful fabrications into pieces that have life beyond the catwalk but retain a sense of painterly uniqueness. Thoughtful yet sensual classicism has always been key at Hermès, where in recent seasons Véronique Nichanian has become more edgy — well, as edgy as Hermès can be. This time around, the goings had a seductive, effortless, ‘80s Armani feel to them. Meanwhile, over at Junya Watanabe, the exploration of twisted formality in a crash of tailoring, patchwork and denim proved particularly engaging, conceived for a badass wearing black lipstick and an inventive wardrobe.

If the discourse on fluid masculinity that was once so central to the ruminations of many men’s designers seems to have been sidelined, it’s probably because a certain delicacy, once perceived as effeminate, has been finally accepted into the rules of men’s dressing. At Taak, Takuya Morikawa, a relative newcomer on the Paris calendar, mixed an almost rococo flair for fabrication and decoration with lines that were light and pure to brilliant results. Jun Takahashi, back on the catwalk with Undercover menswear, delivered an uplifting foray into soft tribalism that felt as energising as spiritual enlightenment and as beautiful as rocaille decorative frenzy.

After the enraged burst she delivered in March, Rei Kawakubo was feeling slightly more hopeful at Comme des Garçons, sending out a posse of kawaii punks in deliciously twisted frock coats and hair clip mohawks. The pieces were gorgeous, if repetitive, with the sidenote of infantilized masculinity that never goes away. At Yohji Yamamoto, by comparison, the men are always grown up and badass, even though this season they looked younger. Working with calligraphic prints, painterly flowers, pervasive lightness and playful asymmetry, Yohji was classic Yohji, and yet the poetry felt particularly intense and touching this time around.

The windswept, billowind shapes at Homme Plissé Issey Miyake were a joy to behold: completely weightless and simply complex, they felt like another affirmation of how good the Miyake output currently is under designer Satoshi Kondo. Two years after the passing away of Issey-san, the label’s unforgettable founder, Kondo keeps honouring his legacy while resolutely moving forward, which is the best embodiment of the Miyake way of thinking.

In a season of grandness and delicacy, Dries Van Noten had the definitive word on both topics with a farewell show after 38 years of tireless dedication to the cause of romantic realism. The collection shone not only for the metallics, the acidic pastels and the silky fabrics; it was Van Noten’s remarkably matter of fact attitude: no retrospective, no après moi, le déluge, no cheesy sentimentalism. On the contrary, what we got was a painterly mix of precise silhouettes and beautiful surfaces pointing resolutely forward, and expressing Van Noten’s unwavering quest for beauty at its best. In an era of extreme self-exposure, Van Noten’s decision to step back felt heroic, poetic and infinitely inspiring — just as the designer has always been.