PARIS — “Paolo Roversi’s photos have always made Comme des Garçons clothes stronger and more beautiful,” designer Rei Kawakubo says.

Collaborations between Kawakubo and the photographer are currently on display in the newly inaugurated Dover Street Market Paris’ courtyard and exhibition space, as well as coating the facade of the Comme des Garçons flagship on Rue du Faubourg Saint Honoré.

Kawakubo is not the only one paying tribute to the iconic Italian photographer at present: Roversi is the subject of a major monograph at the Palais Galliera fashion museum — his first-ever dedicated museum exhibition in Paris — as well as two new books, a large-format catalogue accompanying the Galliera exhibition and “Letters on Light,” an exchange of epistolary essays between Roversi and the philosopher Emanuele Coccia.

Roversi was born in Ravenna, Italy in 1947, the same year Christian Dior debuted his “New Look.” In 1973, he moved to Paris, where his delicate portraits filled with light and shadow made him a trusted collaborator of designers including Kawabuko, Romeo Gigli and Yohji Yamamoto, as well as a sought-after contributor to the likes of Vogue and Egoïste during fashion media’s golden era.

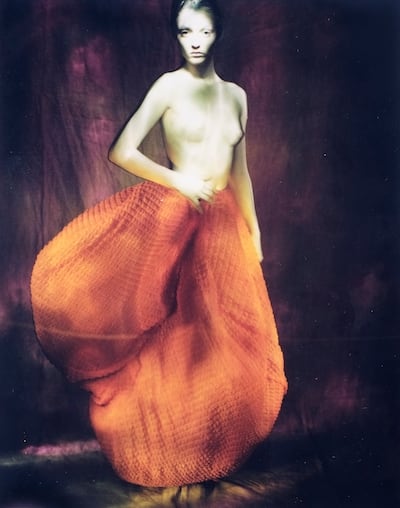

But Roversi is something more than a photographer. His work carries on the legacy of Renaissance and humanist painters, bringing an unusual sense of eternity to the ultra-ephemeral fashion world. His works appear to emanate from an ancient soul, offering lessons in wisdom without speech and radiating something beyond today’s chaotic times.

Nothing looks stolen. While Roversi has contributed to immortalising many of fashion’s most memorable faces from Natalia Vodiaova to Saskia de Brauw and Audrey Marnay, his photographs have little to do with the erotic cliché of the “supermodel.” Each image appears to be drawn — closer to a work by Balthus than a simple photographic exposure.

BoF met Roversi in his studio in Paris’ 14th arrondissement, where he remains faithful to the language of a Renaissance artist, building his work around light.

Laurence Benaïm: Your exhibition at Palais Galliera and the accompanying book are the first monograph dedicated to your work by a Paris museum. What are your thoughts on this milestone celebration?

Paolo Roversi: The exhibition is the fruit of a long process. At Palais Galliera, I worked with [curator] Sylvie Lécailler, who gives an excellent account of this adventure, which began in 2016. I also worked with set designer Ania Martchenko and designer Akari Lisa Ishii from I.C.O.N for the lighting.

I asked them to keep the atmosphere of a palace. And they succeeded marvellously. The common thread was light, with darker, more enchanting rooms that allowed for daylight, and a large table in the middle, reminiscent of Studio Luce. Finally, a sort of “chapel”. There’s something a little religious about it.

What I observe, what I feel, is the great silence of the visitors. You get the impression that they’re in meditation, contemplation. Whether it’s a silver gelatine, Polaroid or carbon print, they all very meticulous and different. Every visitor has physical contact with these photographs—they are not floating images. They have a body, a weight. A presence, a materiality.

LB: And at Dover Street Market?

PR: There it’s a different matter. The entire scenography was conceived and designed by Rei Kawakubo, starting in the courtyard where the images are wrapped around these huge columns. And in the basement, we hung prints around another imposing column. Circling the photographs gives them a particular harmony and mystery. The images are all about Comme des Garçons. It’s a very long story, a story of friendship and loyalty since it began in 1982. I have immense admiration for Rei Kawakubo; her creations are works of art. They’ve always pushed me to surpass myself, to seek out terrain previously unknown to me.

In both cases, I choose to experience the moment as a celebration rather than a consecration. There’s nothing academic about it. It has more to do with joie de vivre than professional pride.

LB: “Le temps long means giving the soul time to surface. And leaving time for chance to intervene,” you confided to Sylvie Lécailler in the [Galliera] exhibition’s catalogue. While you defend a long-term vision for your art, why do you think people are so attracted to your work today?

PR: I’ve always stayed on the margin of fashion, never letting myself get caught up in its whirlwind. I’ve stayed next to the river. And this distance has enabled me to practice this craft and produce images that are both timeless and contemporary, if that’s not too pretentious to say.

LB: “We are all little employees of the sun,” you write. Photography is “an endless childhood”, the sun never going out, it’s an infinite energy” Would you say that your job is to draw light?

PR: I use my little flash like a paintbrush. I believe it’s the light of the heart that enlightens the world. On the other hand, shadows are sometimes the softest and most mysterious of lights.

LB: “I use the word asceticism for Paolo, achieved through intense concentration on his devices, on rays of light, on backgrounds and surfaces,” writes Erri de Lucca in the preface to Lettres sur la lumière (“Letters on light”). How do you navigate the age of artificial intelligence and instantaneous social networking while defending that perspective?

PR: New media are revolutionising photography; every era has its revolutions. But I don’t think that tomorrow will be better or worse. I don’t let myself be overwhelmed by all the new developments. I still develop my films by hand. Technical changes don’t upset my work, nor do they affect me — I continue on my old path. I’m not saying it’s the best one; it’s mine.

LB: How do you think artificial intelligence will impact image creation? For fashion or otherwise?

PR: Photography doesn’t come from a logical language, or from intelligence, but from a feeling. No machine or system can replace it. The more we think, the less we see.

For me, photography doesn’t mean framing an object from external reality to confine it in the camera, but rather awakening something within oneself and bringing it to light. The important thing is to abandon oneself to oneself, to one’s dreams, memories, and emotions. And to look no further than within yourself. You don’t take a photograph, you give it.

LB: You’ve been using Polaroids for over 30 years. You were even nicknamed Paolo-roid. Has the digitalisation of photography changed your profession today? What do you refuse to digitise? Why or why not?

PR: I’m indifferent to floating images. I sometimes take photos with my iPhone, when I don’t have one of my cameras with me. If I want to use one, I need to print it first to give it body. Otherwise, it loses its taste and flavour.

A photograph is a picture of your grandmother in your wallet, on your desk, on the wall. It’s a presence. I love family albums, travel albums, and we continue this tradition. My mother used to say that if a photo didn’t have a date written on the back, it was worthless. Besides, I read books and don’t use tablets. When there are no more books, we’ll know we’ve become a people of barbarians, and I hope that day never comes.

LB: What do you most dislike today?

PR: People who take photos of themselves in front of paintings instead of looking at them. Selfies are to photography what shopping lists are to literature.

LB: How did you manage to reconcile your way of working with the requirements of the brands you shoot for? Is it possible to defend your vision in a world where luxury brands are getting bigger, more expensive, and more demanding in terms of “visibility”?

PR: What we’re seeing today is a standardisation of fashion photography and photography in general. That’s why I love working with Rei Kawakubo. With her, there’s no commercial logic.

LB: “Different photographic cultures are levelling out, and young European photographers are much more familiar with a certain kind of American photography, such as Saul Leiter or William Eggleston,” you write. How do you view fashion photography today? Who are the young photographers who give you hope for this profession?

PR: With a few exceptions, there’s a race to the bottom. I won’t name names. The problem is that pretending to be [something] is often more important than talent or actual knowledge. It’s in discovering and studying the masters that I draw my references. It’s not a question of appropriating a work, but of measuring yourself against those you admire. You can’t just invent yourself as a photographer.

LB: “It was 1982 or 1983, when Kirsten [Owen] came to me and illuminated me with her presence. She has always been my angel of light, falling from the sky into my studio”, you explain in “Letters on Light”. Then there were Guinevere [Van Seenus], Saskia [De Brauw], Natalia [Vodianova] and Audrey [Marnay]. Why are these models so important to your work?

PR: These women allowed me to develop what interests me most: the psychological aspect. Thanks to them, I was able to approach something other than reality. They allowed me to touch, even fleetingly, the mystery of beauty. They have special qualities. It’s not a question of being photogenic, it’s a question of presence. I remember Avedon saying, when he had no presence in front of him: “There’s nobody at home”. There are many girls and boys with beautiful eyes. What counts is having a glance, a character.

LB: What does a good fashion photographer need to understand about fashion, about clothes? What doesn’t he really need to understand?

PR: It’s not important for him to take cutting courses, or to know perfectly how to assemble a sleeve. What’s important is that he’s familiar with each designer’s style and type of model. Photography is an exchange, an encounter. Fashion photography is never a simple reproduction of reality, but always an invention, a creation. You need to know the spirit of fashion as well as the technique. It’s about being an interpreter.

LB: “My little torch gives me exactly this feeling: that it is the light of my mind, my eyes, my heart that will shine on the things of the world”, you write. What would you like to convey?

I’m touched when I see that some of my photos touch people, and young people. I’m not projecting anything. I’m happy when I convey an emotion.

This interview has been edited for clarity and concision.