A hit product can be a brand-making moment for independent designers, helping them build name recognition and pad their bottom line, providing a cushion that allows for taking more risks in the future.

Now, it also means they need to be on guard for dupes.

“[After releasing a collection] the trajectory is ‘how long do we have before everyone starts to release the dupes?’” said Evangeline Titilas, co-founder of With Jéan, an Australian dress and blouse brand beloved by the likes of Hailey Bieber and Dua Lipa.

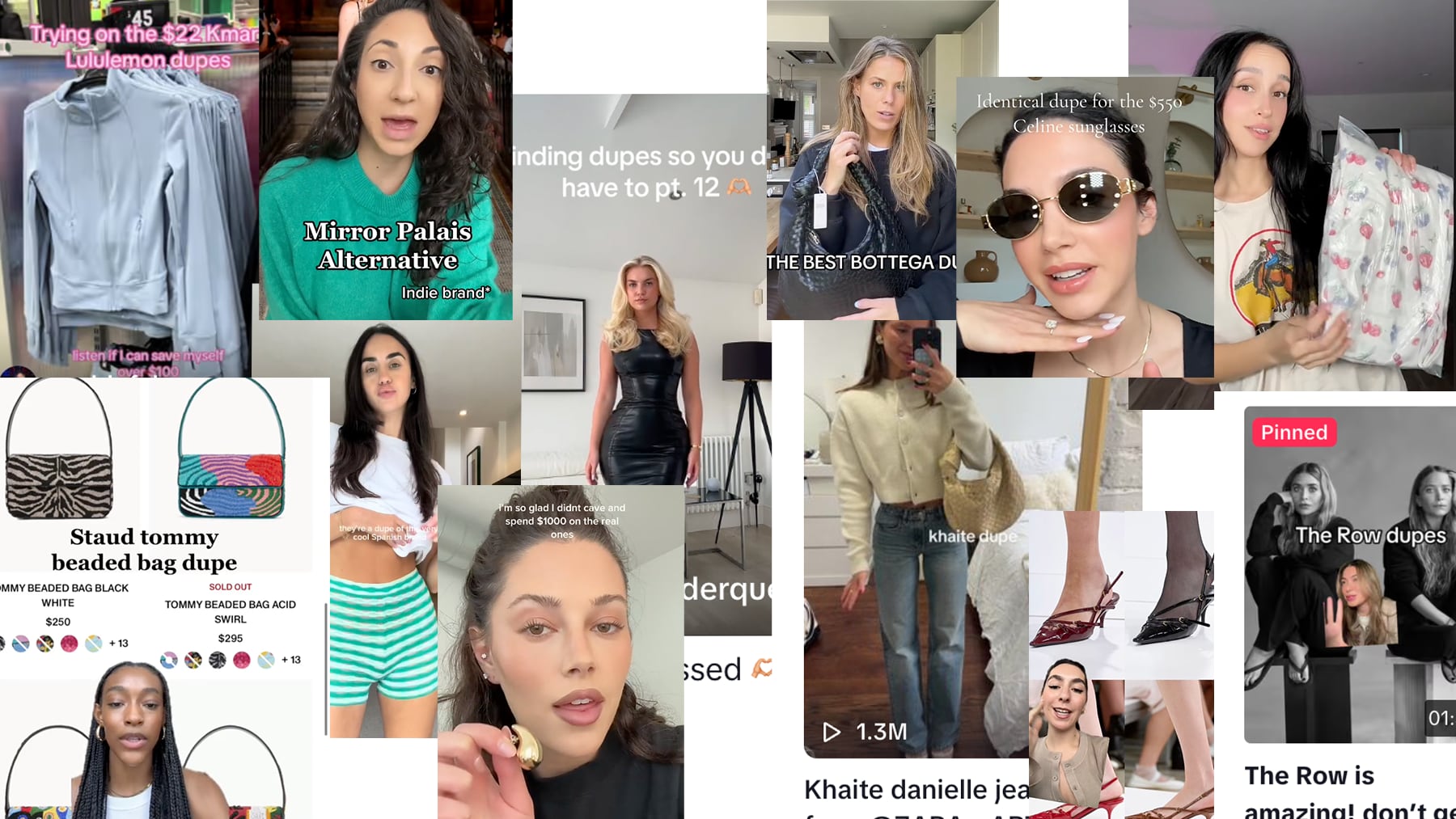

In the past few years, “dupes,” or cheaper facsimiles of popular products have reached a new level of ubiquity in the cultural zeitgeist. TikTok is cluttered with videos recommending alternatives for hyped products like Skims bodysuits, Staud purses, Djerf Avenue pyjamas and Miu Miu jackets; mainstream publications like Teen Vogue and Cosmopolitan regularly do the same.

For brands, dealing with dupes has started to feel inevitable. Lululemon leaned in with an event encouraging people to trade in their faux-Align leggings in May. Cassey Ho, founder of activewear brand Popflex, whose ruffled “Pirouette Skort” shot to virality after Taylor Swift wore it in April, said she currently fights around 70 copycat listings per month.

“If you take a risk on something and you put it in the market and it becomes successful … [dupers] are going to take it,” said Ho.

There’s an ethical grey area: At what point does an item stop being a “dupe” and start being a counterfeit? But that hasn’t stopped dupe culture — which has been propelled by social media’s speedy trend cycle, ultra-fast e-commerce production and scepticism over pricing strategies — from playing a larger role in how consumers shop. With that, it has inevitably had an impact on the fashion system, particularly for independent brands, making it even more difficult to operate in an already tenuous environment.

“It’s really discouraging. We have days where it’s like ‘what’s the point?’” said Titilas.

“It’s not something people think twice about these days. Everyone is like ‘who cares, it’s a dupe, why would I buy [the original] for $149 when I can get it here for $15?’” said With Jéan co-founder Sami Lorking-Tanner.

Dupe-ious Origins

There’s a sliding scale of opinions on what constitutes a dupe versus a counterfeit.

Dupe defenders will argue that an item that looks like or mimics something is a dupe, while an item that pretends to be something is a counterfeit. But the lines are often blurred; Vidyuth Srinivasan, chief executive of luxury authentication firm Entrupy says that in practice, dupes and counterfeits are essentially the same thing. There’s no official distinction; dupes typically become dupes when someone online declares them so.

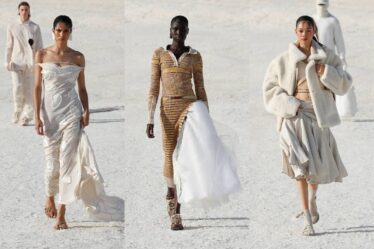

To be sure, copying has always been prevalent in the fashion industry — in the mid-twentieth century, American ready-to-wear makers regularly swiped designs directly off couture runways in Paris. But the level of demand for dupes seen today, as well as conditions fuelling that interest, are unique to this current moment.

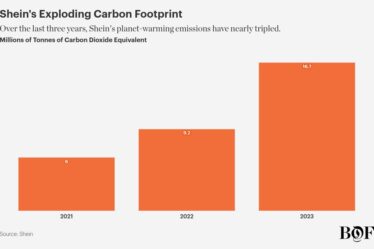

For one, there’s easier access. Dupes proliferate across the e-commerce landscape, at ultra-fast fashion players like Shein and Temu, online shopping giants including Amazon and eBay and mall retailers like Mango, H&M and Zara. And then there’s websites like DHGate and AliExpress, which many shop solely for their selection of dupes.

“I Google a piece from a designer and it shows me so many dupes, I didn’t ask for it,” said Laura Schulte, a Germany-based producer and fashion content creator.

Influencers and tastemakers, incentivised by a potential surge in likes or affiliate commissions thanks to consumer interest, have reason to promote them. On TikTok, videos featuring imitation products, like a faux Bottega Veneta Intrecciato, with a Whatsapp number tucked into the caption for viewers to call to make a purchase circulate, said Henry Du, CEO of brand protection firm Huski.ai. If an account gets shut down, another pops up in its place.

It’s not just ultra luxury products that are susceptible; dupes of Ho’s $60 skirt cost around $20. That reality has made it harder for brands to stomach the argument that the shopper who buys the dupe couldn’t — or wouldn’t — purchase the original.

For designers, figuring out how to talk about dupes is tricky. The fashion industry runs on iteration and it’s hard to prove a particular product as the “original,” even if there’s evidence like timing or a particular fabric used. Condemning dupes can provoke backlash, and no one wants to feel like they’re standing on a soapbox.

Put simply: “I understand why people want to buy cheaper shoes,” said Michelle del Rio, a Paris-based womenswear designer.

Dupe loyalists will argue that the original product isn’t actually unique or that it should be cheaper in the first place. Shoppers are increasingly aware of the discrepancies between what it costs to make a product, and what they’re paying.

“It’s almost an act of rebellion. Consumers are basically saying ‘These prices don’t work for me, this economy doesn’t work for me, but I want what I want, why should I deprive myself?’” said Srinivasan.

A Tricky Business

Simultaneously, Srinivasan said, consumers don’t think about where the products are coming from, why they are so cheap or the fact that it may be a small business that their dupe purchase is harming.

Last week, Del Rio noticed a $100 replica of her $325 black and white Soledad skirt floating around online. The feeling of being ripped off stung, but the idea of losing sales on a margin-driver that took months of development felt existential.

“It scared me. I was like ‘That’s going to cut all of the income I make and limit future collections, it’s going to create confusion in the marketplace,’” she said. “I have to make another friendly price-point thing that I can constantly sell … It changes the whole dynamic of what I want my relationship with fashion to be.”

Because dupes often don’t feature protected trademarks like a logo, brands are left with few ways to hit back when there is perceived theft.

“The court of law is slow and expensive. Let’s say you even get a patent … I have to put in hundreds of thousands of dollars to go to court and they’ll run me dry,” said Ho.

That means they have no choice but to deal with their impact. When an item from a With Jéan drop gets duped — typically, it’s the garments that are most popular and most visible on social media — its shelf life is shortened because “the market becomes saturated and no one wants to wear it,” said Titilas.

With Jéan releases items at low volumes to avoid overproduction and risk. With dupes now so prolific, the brand feels pressure to move faster and produce more, which makes it more likely they’ll be stuck with excess stock. “It’s such a dance on time because you’re trying to get as much in before they start duping … It’s much harder to forecast,” said Titilas.

Ho said her whole brand gets duped, not just her products. Syndicates use Popflex content and product shots, changing the face or race of models to avoid detection. That can be confusing for consumers, she said; bad quality dupes hurt brand perception.

Nia Thomas, a New York-based resortwear designer, said that dupes’ prevalence has forced her to think about them during the design process. Alongside concerns like wholesale appeal, colour choice and pricing, she also must consider how easy it would be to copy a product.

More insidiously, she said, the prevalence of dupes is leading to a larger rift in consumers’ relationship to fashion.

“Dupe culture is adjacent to throw-away culture,” said Thomas, “It’s like ‘Oh I found a duplicate of this and I’ve been wearing it, and now I found something better and I’m going to get that’ … The problem is people don’t understand value anymore.”