LONDON, United Kingdom — Sales of accessories have rocketed in the past decade and, today, account for almost 30 percent of the total global luxury market, up from 18 percent in 2003. Mostly this growth has been driven by handbags.

For consumers, handbags are cost-effective status anchors that can be mixed and matched with other items to suit a wide range of occasions. For brands, handbags offer attractive retail economics, characterised by high sales productivity (sales per square foot) and strong full-price sell-through results.

Yet, there are dark clouds on the handbag horizon.

Simply adding more retail space is no longer a sure route to growth, especially for luxury megabrands like Louis Vuitton, Gucci and Prada, which now claim their store networks are appropriately sized. Prada’s recent decision to curb its space expansion plans is just the latest evidence of this trend.

Adding to the problem, the megabrands have raised their entry-level price points in an attempt to reinforce the perceived exclusivity and desirability of their bags. But while this has reduced the ubiquity of their products, the accompanying reduction in sales volumes makes revenue growth even harder. It has also opened a wide price umbrella under which several aspirational brands, such as Michael Kors and Tory Burch, have crowded, increasing pressure on megabrands from the bottom of the price pyramid.

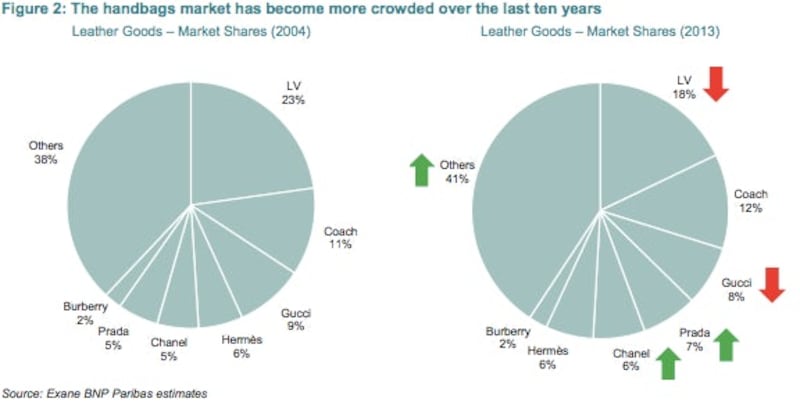

Meanwhile, the top of the pyramid has become very crowded, as high-end fashion players like Dior and Saint Laurent have expanded into accessories. Simultaneously, medium-sized challengers from Balenciaga to Givenchy to Tod’s have also piled up at roughly the same price points as megabrands (and about 20 to 30 percent below this), trying to shore up their weaker apparel or footwear-based models with increased focus on handbags.

Exane BNP Paribas Infographic | Source: Exane BNP Paribas

Unsurprisingly, consumers, spoilt for choice in a crowded handbag market, are showing little loyalty and — especially in China — are swarming from one hot design to another.

Appearances are, however, deceiving. In reality, in the face of these challenges, megabrands are most certainly not moving upmarket to become high-end brands. The median price of their bags is now around €1,500. And, indeed, they have introduced (with much fanfare) new models priced above €3,000. But these brands are not aiming for the top of the pyramid. Certainly, they have raised their entry-level price points and largely relinquished the market below €500, but they still predominantly focus on the €500 to €1,500 price bracket.

Meanwhile, aspirational luxury brands are concentrated in two handbag groups: totes and small bags. Totes are used to carry things around; small bags are typically bought by younger consumers with lower budgets. In both instances, price is a more important purchase criterion than for other bags. Aspirational brands deploy one of three product strategies: attempt to own a shape, concentrate on best sellers or be a lower-priced fast-follower, an approach which may be unsustainable in the long term.

For the medium-sized challengers, handbags can boost space productivity and ease the transition from wholesale to retail. These brands are therefore trying hard to break into the category. But achieving desirability at the appropriate price point is not a straightforward task and challengers seem ambivalent on product strategy, focusing on differentiated shapes on the one hand, while carrying significant assortments in more functional product groups on the other.

While there is much talk about the rapid maturation of luxury consumers away from high-visibility, status-oriented products towards more sophisticated items, high-end handbags by the likes of Bottega Veneta, Céline, Chanel and Hermès are designed to be recognised too. But these brands do not go for easy-to-spot logos and canvas prints. Instead, they focus on very few iconic shapes and emphasise brand styling cues and signature elements. But the idea that sophistication and discretion go hand-in-hand is a myth. The high-end brands provide their customers with the same means of status distinction as do full-logo handbags.

The megabrands still dominate a number of shapes, but are under direct attack in the most functional and lower-priced part of their assortment. They are sandwiched between the high-end players and the aspirational luxury brands, with mid-priced challengers adding to the confusion.

Clearly, this is no time for resting on laurels. In a market awash with choice, a strategy based on past success and reputation, whether associated with a logo, a form or a material, is a recipe for negative like-for-like performance. Louis Vuitton discovered this three years ago and concluded that it needed to innovate, not abandon logos. The same has happened more recently to Prada, which relied on a few distinct shapes (no logo, no canvas) like the more expensive high-end specialists.

What this tells us is that consumers want novelty and get tired faster than in the past. Louis Vuitton has recently got back to growth, achieved largely through new canvas and logo products, including those created in collaboration with third-party designers, riffing on the LV monogram, of all things. The fact that Prada became a casualty highlights the possibility of fatigue risk from over-reliance on a few coveted shapes.

This may sound blasphemous, but even Chanel and Hermès may not be safe in the brave new world of handbags if they fail to replicate their past landmark successes with new blockbuster products.

Luca Solca is the head of luxury goods at BNP Exane Paribas.