PARIS — White roses, white sofas, black marble tables and leather handbags. All is order and simplicity in the monochromatic boutiques that have helped propel Saint Laurent from a storied but mid-sized French designer house to one of global luxury’s superbrands.

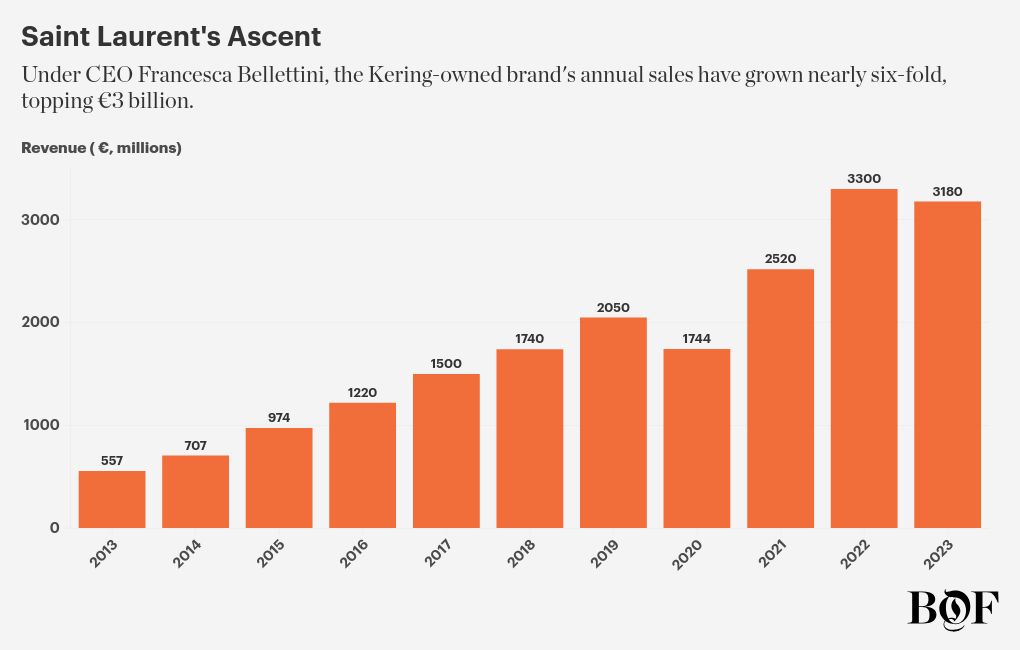

The current outlook for luxury is far more messy, and so is the mission facing the brand’s chief executive Francesca Bellettini. After leading Saint Laurent from €550 million ($613 million) in annual sales in 2013 to €3.2 billion ($3.57 billion) ten years later, sales have slipped as revenues have dipped as the world’s post-pandemic fervour for luxury fashion wanes. How far demand will fall, and where the industry’s next wave of growth will come from, is anyone’s guess.

Bellettini — a 54-year-old Italian with a broad smile and regal mane of dark curls — won’t just have to pull Saint Laurent out of the slump. In September 2023, the executive was named deputy CEO for brand development at owner Kering, supervising all of the group’s units including Gucci, Balenciaga, Bottega Veneta and McQueen, in addition to her CEO role at YSL. (Former chief financial officer Jean-Marc Dupleix was also promoted as co-deputy CEO for finance and operations.)

At Saint Laurent, Bellettini earned a reputation for controlled execution and remarkably consistent results. Her promotion at Kering made her one of fashion’s most powerful women, alongside Inditex chairperson Marta Ortega, Chanel CEO Leena Nair and LVMH scion Delphine Arnault. But she’s also the latest businesswoman to face the “glass cliff”— a term for when women are given leadership roles in times of crisis, when the risk of failure is high.

Kering’s shares are trading at their lowest level since 2017 as flagship Gucci struggles to gain traction for its more understated, sartorial vision under a new creative director and CEO. The group, controlled by French billionaire François-Henri Pinault, saw sales fall 11 percent in the first half, while operating profit tumbled 42 percent. Last year, the group’s sales fell 2 percent to €19.6 billion ($21.9 billion). The company has pledged to cut cost in line with its new reality, making it harder for Bellettini to reignite growth.

The issue isn’t just Gucci. Saint Laurent’s sales fell 7 percent in the first half of the year amid sagging demand for its more accessible “Envelope” bag family, while more luxe propositions like the €4,100 ($4,575) Icare tote remain out of reach for many brand devotees. Balenciaga has had to fight its way back from a public relations scandal while navigating cooling demand for the merch-inspired luxury hoodies and chunky sneakers that powered its previous wave of growth under designer Demna. And Alexander McQueen is onboarding a new creative director after Sarah Burton quit the British brand taking nearly three decades of expertise — and a direct link to Lee McQueen — with her.

Kering has said it plans to hold steady in its strategy of refocusing its business toward more timeless, upscale carry-over items — lowering its dependence on radical designer rebrands and entry-priced novelties, which had been catnip to young luxury customers in the company’s previous era of growth. It’s also forged ahead with clamping down on distribution to wholesalers, resellers and outlets.

Success will depend on careful execution.

Doctor Bellettini

On a sunny September morning, birds are chirping in the garden of the 17th century hospital complex that now houses Kering’s Paris headquarters, the bucolic sounds punctuated by the occasional clack of heels on the cobblestone courtyard.

The building was previously named “Hospice of the Incurables,” but Kering’s leadership is betting its own recovery is merely a question of time. Its brands are among the fashion industry’s most iconic and beloved, and the key Chinese market is sure to emerge from its current gloom eventually. (Indeed, shares across the sector rose last week when the Chinese Communist Party announced a fresh round of fiscal stimulus.)

In the meantime, the doctor is in session: upbeat, energetic and dressed in a body-skimming silk blouse and a Qeelin ring depicting a French bulldog. (She is mad about them; Saint Laurent creative director Anthony Vaccarello gave her one for Christmas a few years back.)

“The moves we are making will allow us to grow and to be stronger than before, because the growth and the business is going to be more controlled,” Bellettini said. “In this moment of crisis, we need to evaluate very well. We need to stay focused on the things we can control, and we need to fix the things we know we can do better.”

Kering’s hope is that Bellettini will be able to replicate the tightly controlled, ultra-consistent approach to fashion that has driven success at Saint Laurent for brands across the group, putting an end to the boom-and-bust cycles that have dogged the company (particularly designer-driven flagship Gucci) in contrast to the steadier performance of rivals like LVMH, Chanel and Hermès.

Bellettini joined Saint Laurent in 2013, when the brand had annual sales around €550 million. While then-creative director Hedi Slimane cleaned up the brand image — simplifying its marketing and product offer with a crisp, monochromatic aesthetic and easy-to-wear, nostalgic designs — Bellettini set about cleaning up its business, cutting out licensing deals and embarking on a long-term plan to transform the company from a label dependent on ready-to-wear and wholesalers to an accessories powerhouse that sells primarily through its own retail stores.

Sales didn’t hit a bump, but rather accelerated following a carefully managed designer transition in 2016. The brand melded Slimane’s punchy marketing template with sexed-up, cinematic collections by successor Vaccarello, who has gone on to spotlight and reinterpreted many of the most striking and innovative moments from Yves Saint Laurent’s archive. By 2023, annual revenue hit €3.2 billion, up six-fold from when Bellettini arrived at the brand a decade before.

“Patience, but with a sense of urgency,” has been her maxim at the brand, Bellettini said.

“I learned you have to have a portfolio of actions to create results in the short, medium and long term — and make sure that you know very well which they are, to know when you should expect to see results,” Bellettini said. “It would be very wrong to implement an action that is supposed to give results in the medium to long term and expect results immediately, as well as to implement an action that is supposed to give results immediately, and not realise that this is not happening.”

Kering Shakeup

Bellettini’s arrival in the deputy CEO role came amid a broader shake-up in Kering’s senior ranks. Gucci’s designer Alessandro Michele and CEO Marco Bizzarri exited after a historic sales boom was followed by prolonged stagnation. Kering CEO Pinault’s longtime deputy Jean-François Palus stepped in as Gucci’s interim CEO alongside new creative director Sabato de Sarno, while Bellettini and group CFO Jean-Marc Duplaix were promoted to steer the group as co-deputy CEOs.

“We are building a more robust organisation to fully capture the growth of the global luxury market,” Pinault said at the time. “While being instrumental in multiplying revenues sixfold since she joined Saint Laurent, she has been a fantastic partner, and all brands as well as the group will now benefit from her expertise.”

Belletini’s appointment gave hope to investors who were eager to see more dramatic changes at the company, and who had long marvelled at her steady-handed leadership and blockbuster results at Saint Laurent. Still, the dual role raised questions: Could Bellettini realistically handle such a complex dossier — including Gucci’s turnaround and a designer change at McQueen, not to mention the creation of an in-house beauty division — at the same time as continuing to run Saint Laurent?

Bellettini says she’s retooled her reporting lines and approach at Saint Laurent, increasingly delegating operations while continuing to be involved in “every decision that is related to the confirmation of the strategy.”

“When you are small, maybe it’s easier to run a company with a lot of 1-to-1 meetings — short, fast, a few people. When a company becomes bigger it’s more about meeting together, like a sort of restitution,” she said. “We focus the attention on decisions about the priorities of the company, on store openings, on markets to enter or eventually not.”

A self-described “control-freak,” Bellettini has become increasingly committed to an organisational approach. “The more a brand grows, the more you need to empower people to be able to take decisions,” she said. “Paradoxically, with the right delegation, you control things better. Being a control freak doesn’t mean that you have to look at everything [yourself]. It means you want to know.”

As deputy CEO at the group level, she says she’s been able to take over close oversight of each unit, going into greater detail with executives leveraging her insights as a fellow brand CEO. Increased visibility of the company’s other units has also changed the way she leads Saint Laurent. “Now that I oversee all the brands with the mentality of a brand CEO, it’s easier to recognise what is a market trend, a market challenge, and what is specific to the brand,” Bellettini said.

Lower sales to aspirational clients is a market-wide trend, for example — “you can act on it, but you can’t control it,” she explained. Knowing this “allows all of us to focus more on the things that we can control and to try to tackle together,” she said.

The new structure has allowed François-Henri Pinault to take a step back from operations. “He still maintains a relationship with the brands, with the creative director and with the CEO, but it has created a little bit more distance, which allows him to intervene for the super, super important topics,” she said.

Cruising the Aeolian Islands this summer, Bellettini tried her hand at skippering the boat, and ended up spending several hours at the helm. She learned to monitor feedback from the tiller, from the tension in various lines. Staying on course required constant but subtle moves.

“You feel a lot of energy while you have the wheel in your hands, but in reality you have to do very little movement to go straight,” she said. “Running a company, it’s very similar. When you want to do an evolution, it’s a sum of very many small adjustments that make you go towards your route.”

In addition to the bolder shakeups at Gucci and McQueen, subtle adjustments abound at Kering — a departure from the group’s previous culture of bold and radical rebrands.

At Saint Laurent, Vaccarello has injected more colour in recent collections as well as more androgynous, tailored silhouettes to complement options for sexed-up glamour. Stores are softer and more inviting, with warm wood tones and blues adding texture and nuance to the brand’s greyscale, concrete-and-marble concept. Price hikes have slowed (and even been reversed for a handful of products in some regions) while customers catch up with the label’s higher-end ambitions.

At Bottega Veneta, recent collections by Matthieu Blazy celebrated craftsmanship, art and post-modern furniture design. The designs on the runway are whimsical and eclectic — but followed up in stores with plenty of subtle updates to its core range of chocolate or black intrecciato handbags. The brand has steadily tapered its wholesale trade in less-expensive card-holders and skate sneakers, rebalancing its business to sell mainly at retail, complemented by avant-garde wholesale stockists like Dover Street Market in Paris.

Balenciaga has stuck with its creative and business leadership throughout a long and difficult reset, and is seeing renewed traction with its motorcycle bags and a best-selling Hermès-inspired style, the Rodeo. The brand is also putting extra focus on its annual couture collections in a bid to restore its upscale image and reduce its dependence on sporty, entry-priced merch.

Gucci’s Turnaround

Bellettini’s success at Kering will mostly depend on achieving results at flagship brand Gucci, which accounts for roughly half of the group’s revenues and two-thirds of operating profit. There, the strategy is hardly one of subtle tweaks, but an aesthetic and organisational overhaul.

Two years after announcing a new heritage strategy — a plan to balance fashion novelty with promoting long-standing best-sellers — and nearly one year since replacing its senior team, Gucci remains in steep decline. Sales plunged 20 percent in the first half of the year.

While momentum surrounding Michele’s kitschy, off-kilter vision had certainly cooled, recent moves to drastically rein in the label’s maximalist verve have made it trickier to keep existing customers engaged. Meanwhile, new designer De Sarno’s milder aesthetic appeared to have the potential to speak to a wider audience, but has yet to catch fire after six shows. The situation isn’t helped by the fact that updated product has only gradually trickled into stores, amid supply-chain holdups and the process of working through existing retail stock.

With its sprawling network of suppliers, Gucci can either make things fast or in large quantities — but rarely both, Bellettini explained. “Even some big factories might be very flexible, but produce an amount of product that touches only a few stores compared to the scale of this brand,” she said. “The real wave of deliveries to say if the new product is really working — we’re basically starting to see it now, because there are so many stores and the company is so retail driven.”

The brand is currently in a “transformation,” but needs to be careful to preserve both sides of Gucci, Bellettini said. “It’s being a brand with a very strong identity, from craft and leather goods — because we need to remember what is the DNA of Gucci — but at the same time [having] a super strong fashion component … The moments when Gucci was most successful, it’s when the two things were combined together.”

But attempting to reassert Gucci’s heritage while simultaneously developing a new fashion vision is a tricky endeavour; even more so under a first-time creative director and first-time brand CEO (De Sarno was previously a behind-the-scenes designer overseeing Valentino’s ready-to-wear; Palus’ previous roles have mostly been group-level and governance positions).

Results remain under pressure, but “what I see from inside is that the company is absolutely going in the right direction, because the aesthetic that Sabato has brought allows us to clean up and reset,” Bellettini said.

Slowly but surely, the brand is working to fill the void left by CEO Bizzarri (not to mention the scores of designers, merchandisers and marketeers that have dispersed during the current shakeup). “It’s a company that is so big, it cannot work with a one-man show. It’s too risky, absolutely too risky. And at Gucci there was a little bit of that culture before, of a directional, strong leader — which is needed when you are controlling a humongous growth,” Bellettini said. “In a moment of transition, we feel that a culture that is a little bit more collegial, that puts together different competencies, is what’s needed.”

Under Bellettini, Gucci has brought on a new industrial director — Prada’s former COO Massimo Vian — as well as a deputy CEO hired from Louis Vuitton, Stefano Cantino, charged with retooling marketing, communications and merchandising, and seen as a leading candidate to succeed Palus.

A Woman’s View from the Top

As Saint Laurent’s leader, Francesca Bellettini was already one of just a handful of women executives to sit atop a luxury fashion brand. Her promotion to the Kering level has now made her one of the most powerful women in fashion: set to play a key role in hiring and firing CEOs and designers, and championing future acquisitions for the group.

Kering recently acquired a large minority stake in Valentino, with the option to buy the rest from Qatar’s Mayhoola within a few years. As such, Michele remains in the mix at Kering: the designer showed his first collection for Valentino at Paris Fashion Week on Sunday.

Being placed in a highly visible role at such a turbulent moment for Kering could look like a poisoned gift for Bellettini — another case of a distressed company calling on a woman to clean things up.

But she doesn’t see it that way. “I didn’t have this impression, to be honest. My role is to develop the brands. The discussion is about how to take the brands to the next level — not a restructuring kind of business plan,” she said. “Of course the position and the moment is challenging, but it is challenging for everyone.”

Bellettini says she hopes she can inspire more women to take on leadership roles — and to inspire more deciders to give them a chance. In order to make more space for women, as well as other underrepresented profiles, the fashion industry should become more open to facilitating career moves across industries and specialties at every level, she said.

“I like people who are open to change, who are open to lateral moves and not only vertical moves in their careers … I think companies can do a little more to see the starting point where someone is and help them accelerate,” she said. “If you see that a person didn’t have the opportunity to finish their studies, or that they don’t have certain skills but they have that brightness, that light in their eyes, you can help them with training and programmes.”

Bellettini herself made that kind of lateral move when she jumped ship from a well-paid investment banking role to join Prada. After working deals for Prada chairman Patrizio Bertelli, the executive offered her a role as operations manager for the Milanese group’s new acquisitions, which at the time included Jil Sander.

“I felt like a fish out of water. Imagine a banker — running spreadsheets and numbers and everything has to line up — being thrown in an industry driven by creativity inside a group like Prada,” Bellettini said.

But Bellettini went on to forge a reputation for working in close partnership — and successfully — with designers, merchandisers and image makers. “Little by little, I fell in love with creativity. And I saw the beauty for a manager of being able to work next to creativity, to support it and make it become a business. That is still the biggest pleasure I find in our industry.”

Potential Successor

Bellettini’s increased visibility in the group has added fuel to the sense that she is the top contender to one day succeed François-Henri Pinault leading the group..

At 62, there’s no rush for Pinault to hand over the reins. But the executive has steadily expanded his responsibilities outside Kering via his family’s investment vehicle Artemis. In addition to his father François Pinault, 88, scaling back his role supervising Artemis’ holdings like auction giant Christie’s over the past decade, the Pinaults acquired leading talent agency CAA last year in a $7 billion deal.

Bellettini said Pinault’s succession was not part of Kering’s or Artemis’ immediate plans. “At the moment, we have enough on our plates to focus on. My personal ambitions, to be honest, come after,” she said.

But would she want the job? “The obvious answer is yes,” Bellettini said. “But it’s a decision that doesn’t depend on me … It’s certainly not in my agenda or the short to medium term. It’s something that if it comes, it’s going to come in the future.”