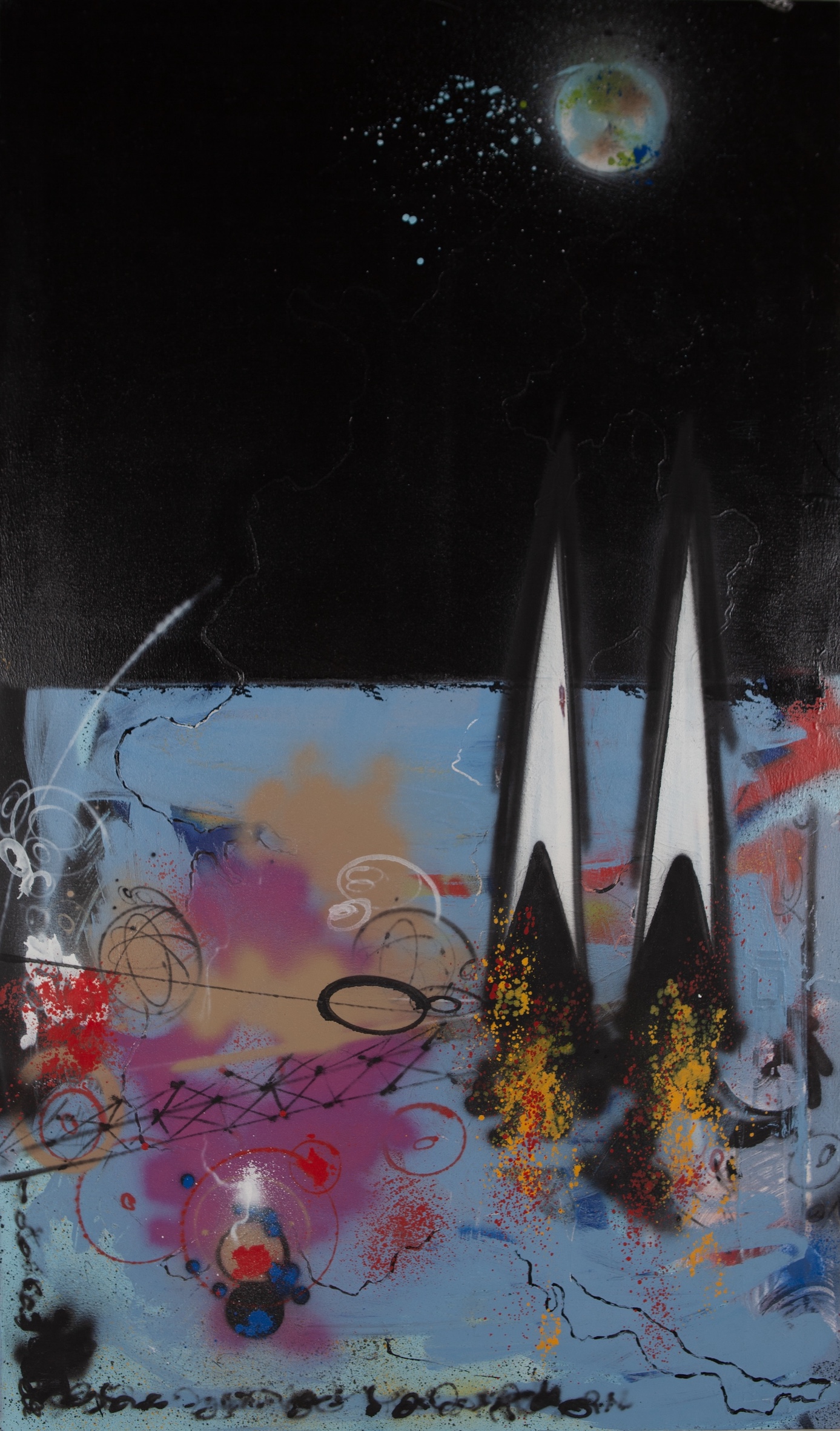

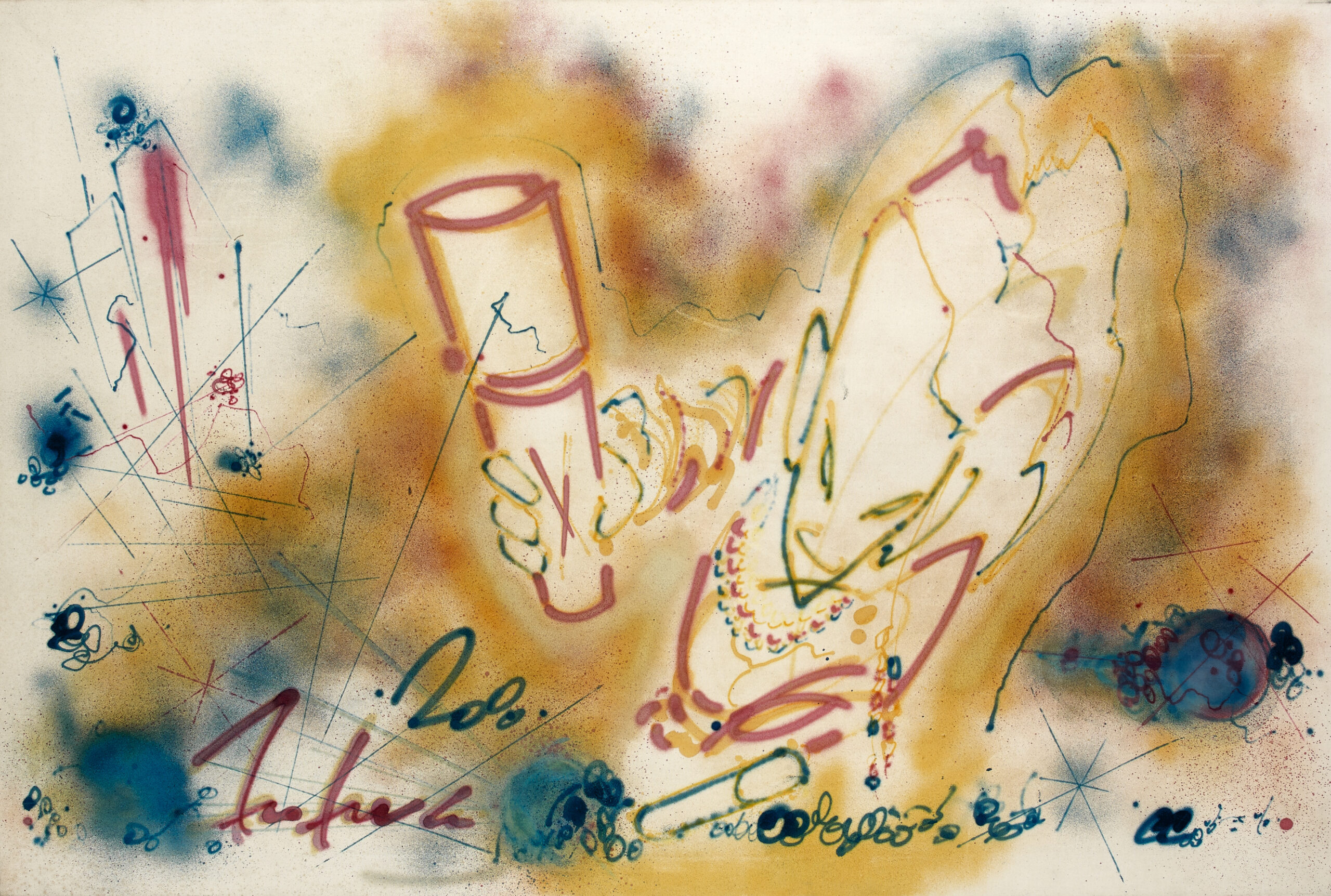

FUTURA 2000 might just be the king of collaborations. Born Leonard Hilton McGurr, the legendary subway graffiti artist and friend of the Factory was one of the first, along with Basquiat and Haring, to introduce street art to the institutions in the ’80s, which kicked off an illustrious career of creating collab grails with everyone from Supreme to Murakami to Rei Kawakubo. This Sunday, five decades of FUTURA art and paraphernelia go on display at the Bronx Museum for the opening of BREAKING OUT, the largest ever exhibition of the artist’s experiments in abstraction. And it happens to coincide with a celebration of his collaborative spirit: FUTURA and Marc Jacobs’ eighth capsule together dropped this week, in honor of the brand’s 40th anniversary; so trusting is Jacobs of his longtime friend that he gave gim free rein to spray-paint his signature, bestselling tote bag. “I was like, ‘Wow, Marc’s letting me touch his number one thing,’” FUTURA joked when the pair called each other up last month to talk authenticity, punk aesthetics, and the golden age of New York art.

———

FUTURA 2000: Where are you there, Marc?

MARC JACOBS: I’m in Rye, New York. I moved. I was born and raised in New York City and lived all my life there.

FUTURA 2000: Were you downtown?

JACOBS: No, Upper West Side. I swore I would never leave the city. You couldn’t get me to live anywhere else. Forget it. And of course, at Vuitton, I lived half the year in New York and half the year in Paris. I traveled back and forth. But I never considered that I was living in Paris. And then a few years ago, just before the pandemic, we saw this house and we just fell in love. I didn’t expect this to happen, but we put years of work into it, and now I’m living here full time and I commute to the city.

FUTURA 2000: That’s crazy. So what is that, an hour?

JACOBS: Well, depending on traffic. We always go past Fort Tryon Park where I used to live, Dyckman Street.

FUTURA 2000: Well, it looks beautiful.

JACOBS: Yeah, it’s really amazing out here. What’s behind me is not the best view, but in the other direction, I’ve got the Long Island Sound, so that’s pretty incredible.

FUTURA 2000: That sounds nice.

JACOBS: What’s up with you?

FUTURA 2000: I’m just in the queue. I’m waiting for all these things to happen right now. Waiting for the Olympic games, waiting for the show at the Bronx Museum, waiting for our thing to happen.

JACOBS: Yeah. Tell me about our thing. How was that for you?

FUTURA 2000: Well, honestly, Marc, as someone who’s been around the city for so many years, I always am observant of what’s going on in different scenes. We had discussed previously how, although we weren’t really in the same community, we were in the same social construct of these openings and parties where I would see you from afar. I’ve always admired you. Our collaboration is a big moment for me. I began 30 years ago, independent. We had a silk-screening press, and we were really trying to DIY it. I know the struggle and what it takes to create on a grassroots level, so to be working with you, Marc, it’s quite an honor. Thank you.

JACOBS: Well, thank you. Just recently, somebody was asking me in passing how I knew of you. We go back to that magical period in New York. Although we didn’t have a personal connection then, I revered you and your creativity, and as a company we look for that in people we collaborate with.

FUTURA 2000: And you have the next generation of folks coming through. Unlike back in the day, where everything we were doing was quite challenging and provocative, today a 20 or 30-year-old individual has the sensibility for it. Back then, the shows we would do would attract a crowd and the energy was exciting, but there was a lot of the unknown and the unknown can be difficult to confront.

JACOBS: Right.

FUTURA 2000: The next generation is in place to understand everything. One of my artist friends in Holland, Boris, also known as Delta, who’s an amazing artist, his assistant’s are 22 or 23. It proves that just because you’re right out of school, it doesn’t mean you don’t also have the skill set and the wherewithal. That mentality didn’t exist back then because things hadn’t evolved on such a mega scale. It was all word of mouth. It took much longer to realize our ideas. There’s a lot bad about the current tech situation, but there’s still the very positive element where communication is easier. Even this project came together within the last 18 months.

JACOBS: Yeah.

FUTURA 2000: When this originated, I didn’t even know I was going to have the show at the Bronx Museum.

JACOBS: Oh, you didn’t know that was coming up?

FUTURA 2000: No, we didn’t coordinate that.

JACOBS: That’s the magic of the universe though.

FUTURA 2000: It is. It’s like the angels in your life are there to guide you and aid you in your mission.

JACOBS: Each thing amplifies the other.

FUTURA 2000: Yeah. It helps us to tell our story. You kind of went off too. You went a little bit further out. Some of the jewelry pieces—

JACOBS Yeah, the earrings.

FUTURA 2000: I’m not even in that world, per se. So for you to let me in…

JACOBS: Well, there are two audiences here, which will intermingle and learn about each other.

FUTURA 2000: And some of the pieces are just so amazing. Your tote bag is a symbol. It’s what people think of when they think of you. I was like, “Wow, Marc’s letting me touch his number one thing.”

JACOBS: It’s become kind of an iconic piece and it does feel democratic. More people can access it. So it’s a great canvas for artwork, and so it’s cool that your artwork is appearing on our blank canvas, which is the tote bag. I have experiences with bags by artists from when I was at Vuitton. You don’t have to be a certain size or height, everybody can buy a bag. And then to have it be redesigned by the artist, they become these covetable pieces.

FUTURA 2000: Right. My first recollection [of that from] of anyone from our crew, the downtown scene, was probably through Keith Haring, rest in peace. When Stephen Sprouse was first milling around and doing that thing, we were just becoming familiar with what was going on in Europe and Asia. You infiltrated these brands that previously were just seen from afar. In the same way, I respect Nigo, in terms of collaborations.

JACOBS: Yes.

FUTURA 2000: He’s sort of like the god of it, the poster boy. Talk about a roadmap. He’s just got something that’s brilliant. And it’s a bit of a rush to have arrived at a moment where we’re boys and you’re allowing me to collaborate with you. You’re a global thing, dude. Come on, you’re Marc Jacobs.

JACOBS: I don’t know what that means, but thank you.

FUTURA 2000: I’m proud of this city and the creative people I’ve met through my life here. If you get past the perception of how we are here in New York, we’re really amazing down-to-earth people, truthful and authentic. “Authentic”—that’s something I admire in you, Marc. What’s going on with your nails right there? I see there’s something happening.

JACOBS: Yeah. There’s something happening.

FUTURA 2000: You were selling metro tickets in the subway. It was all the MTA subway women who had the craziest nails.

JACOBS: I know.

FUTURA 2000: Really next level. It’s incredible.

JACOBS: I think with everything going on in the world, maybe even without it, we live in such an interesting time. There’s so many questions I ask myself. I want to challenge norms. I know that long, decorated nails belong to and were brought into pop culture by Black women. And I think, “Okay, so they’re not for white people, they’re not for boys, so I think I’ll do that.”

FUTURA 2000: So let me do that.

JACOBS: So let me do that.

FUTURA 2000: Maybe 20 years ago, Marc, I had a moment where my hair had grown and I had it in almost like a double braided, “Are you an American Indian? Are you Snoop Dogg?” Something like that. But I did go for the black nails. I had a moment for about a year. I got to go to the salon. My girl, she’s hooking it up. And I was a bit of a weirdo, no doubt. But it was around the time I did a figure called “Nosferatu.” That movie’s out right now.

JACOBS: Yeah.

FUTURA 2000: But Nosferatu had always been a thing.

JACOBS: That was the original name for Dracula, right?

FUTURA 2000: Exactly. I’m a sucker for history, and I’m also old enough to have grown up with some of those references when I was young. Things just get rebooted and everything is back again. But when during the Nosferatu moment, that’s when I adopted the look. The nails are very conscious of that. I was in the UK in the ‘80s. I worked with The Clash at some point. I know all about the punks. Loved John Lydon, a weird character. I didn’t really go there then, but later I did. Because, like you said, you want to defy perceptions, and make people double-check that at the door.

JACOBS: Maybe I’m making this way too simple, but when I first knew of you, that’s exactly what your art was doing. That was such a Duchamp thing of “This can be art.” What you and Keith and other people were doing, there was no question in your mind that you were making art, but the art world thought, “Oh, what we knew as art is being challenged by this.” So constantly fucking with perception, I think, is always a good way to go.

FUTURA 2000: Well, initially when I arrived—unlike Keith, Kenny, Jean-Michel, these people who had a bit more art knowledge, whether they went to school or had read books about art history—I was a bit more ignorant then, because it simply wasn’t my backstory. I didn’t go to art school. I couldn’t get into Art and Design [High School].

JACOBS: That’s where I went.

FUTURA 2000: A&D?

JACOBS: Yeah.

FUTURA 2000: Growing up in New York, my thing in the ‘70s was not art, but graphic design. I thought that was the future, and I was trying to present myself as a graphic artist, but it just got shut down.

JACOBS: Do you remember what your first artistic expression was? Or what compelled you?

FUTURA 2000: It was 1980 when I made my first “painting,” something static and not illegal. I had a studio with Fred Brathwaite, aka Fab 5 Freddy, on 2nd Street and Avenue B. Truth be told, Freddie contacted me recently saying, “Hey man, I’ve got this painting of yours.” I think it’s one of your first paintings that I made for him at this other studio we had up in the Upper West Side. He said we’re going to try to get it in the Brooklyn Museum.

JACOBS: Oh, wow.

FUTURA 2000: So that’s kind of cool. But even that piece was a gift. Everything then was just spontaneous flow. There was no economics, there was no money. It was just all so much fun and cool. “Oh, yeah, here, wow, you like it, please have it.” Little did I know that painting has a value.

JACOBS: As an artist, do you think you can still tap into that naive, wonderful energy that you had back then?

FUTURA 2000: If the circumstances are such where it isn’t altered by some sort of a transaction. I like it if I’m just coming to your place and you’re like, “Hey, Lenny, do you want to spray up the wall here or whatever?” Public art works the best. There’s nothing to do, but do the thing. Transaction changes everything.

JACOBS: Right. In terms of our collaboration, there was a plan, it wasn’t a surprise that this would be for commercial consumption. But can you still tap into being free within that structure?

FUTURA 2000: Yeah, I do. This is different. Moving forward, I still want to be there to contribute energy. Whatever it takes to really see it through. I want to be very much engaged in the drop. The reward isn’t always in the paper. That doesn’t move me. And to be honest, I think the fact that it’s taken me this long for these things to happen, whether it’s collaborations or getting into an institution… I’m not ignorant. I’m actually good with numbers. So if I wanted to do that, I feel like I could have done that. But along the way, it’s been about my integrity and what really motivates me. That’s a problem I think I’ve always grappled with. I can sell a painting now, and it would’ve taken my dad two or three years to earn that. Those things still touch me. My people left, so they had no idea, they saw none of this. However, I remember not just the love, but the difficulty and the struggle. I always wanted to try to find a way to improve all that, to make it less stressful. And I’m an only child, so it wasn’t like once my people were gone, I had an extended family. I’ve been a loner, and now I have two beautiful children, and obviously my wife, she’s my most important person and collaborator.

JACOBS: It’s crucial. I know. The guy who recognized me at my Parsons School of Design fashion show was the one who went to bat for me when the company he worked for needed a designer. He was like, “I know this guy has no experience, and he’s just a cool kid from New York, and I think you should give him a shot.” When there were forces that were trying to water me down or gear it in one direction or the other, he would fight for me. So as you were describing the collaboration you have with your wife, I was thinking that it’s so important to have somebody who believes in you, who loves you, and who’s taking care of stuff so you can do what you do.

FUTURA 2000: Yes.

JACOBS: But when you were talking about those that left, I thought of my grandmother who raised me. My grandmother died just before I got this incredible job to do Perry Ellis when I was 25 years old, and she was my biggest supporter. This is when the Upper West Side was a no man’s land. It was like Needle Park, and there was the butcher and the hardware store and the dry cleaner. I’d go with her to the butcher, and she’d tell them, “My grandson’s going to be a great designer someday.” And we went to the supermarket and she’d say, “My grandson’s going to be a great designer someday.” And unfortunately, she wasn’t around to see what happened. So I could really relate when you were talking about that.

FUTURA 2000: Do you sense that she is still in the afterlife?

JACOBS: Oh, yeah. My dad died when I was 7. My grandmother was his mother. I totally feel that they are aware of what’s going on with me.

FUTURA 2000: Well, we’re on this path and the machine is moving efficiently, then it’s like, “Where can we take it?” That’s part of the ongoing journey. All things have consequences. I very much am awed by what you guys created by putting my stuff onto pieces that I would’ve never envisioned. Even when you came out to the studio, mid-pandemic—

JACOBS: Was it?

FUTURA 2000: It was like, 2021. It was organic. We got to meet and chill and talk about what could be. Now we’re having this chat about what is. Your ability to generate this exposure is exciting. Some of your clients are going to learn about me for the first time.

JACOBS: Yes.

FUTURA 2000: And I never know where people enter that door. It could be a record cover, it could be a commercial project, but for a lot of people, it’s going to be through Marc Jacobs.

JACOBS: Some, for sure.

FUTURA 2000: I think so. And it’s just a great look back to the show. We’re going to be very close by September. I look forward to that, Marc.

JACOBS: Me too. It all has to start somewhere.

FUTURA 2000: Yes, it does. I’m going to send you a photo of my Nosferatu moment.