The 24 hours after the first moon of the lunisolar calendar are a chaotic multi-stop itinerary for Junda Khoo, chef and co-owner of Sydney’s Ho Jiak restaurants. On Sunday 22 January (lunar new year) he will juggle duties as a father, husband, chef, employer … and lion tamer.

It begins at home, where his three children kneel before Khoo and his wife, Sharon, to wish them a healthy and happy new year. In return, the kids receive lucky red envelopes filled with cash. “We kiss, we hug, and then I’ll make breakfast,” says Khoo.

At lunchtime, he visits his Chinatown restaurant to give more red packets to staff and oversee the booked-out lunch service for 110 diners. That is, until a three-person Chinese lion dance bursts into the kitchen, running riot between the pots and pans, and spraying the place with chewed-up iceberg lettuce. “If you catch it, then your dreams and wishes will come true,” says Khoo.

In the late afternoon, he heads home where his children are hosting a kids’ lunar new year party, before winding down with a dinner banquet with family – yes, he’s cooking that too. “After dinner, then I get to chill.”

Sunday is normally his day off. But the rush is worth it. “You only do it once a year and I love it. It’s my favourite time of the year,” Khoo says.

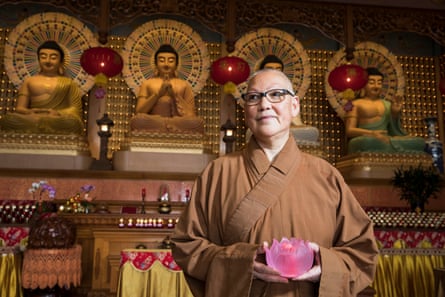

At Nan Tien Temple near Wollongong, a 90-minute drive south of Sydney, Venerable Miao You is preparing for thousands of visitors to descend upon the temple.

Not all Buddhists observe lunar new year. Buddhism was founded in the late sixth century in the land we now call India, but Chinese Buddhists have long incorporated the cultural festival into their faith. “It becomes a custom, a culture, enmeshed with religion as well,” says Venerable Miao You.

On Saturday night – lunar new year’s eve – the temple holds two evening prayer ceremonies farewelling the old year, and welcoming the new. The Venerable’s duties don’t finish until about 2am. They recommence just hours later when the temple gates open at 8am.

A highlight of her morning is the new year blessing ceremony in the main shrine. The abbess (the “CEO of the temple”) leads a congregation, chanting 1000 names of past, present and future Buddhas. “It helps remind us that we too one day could be enlightened and be a Buddha,” she says. “When we chant the names of the Buddhas and pray to the Buddhas … it helps remind us that we too one day could be enlightened and be a Buddha.”

The new year symbolises new beginnings, she says. “If you approach the year with positiveness, positive things will emerge in your life. You know, it’s kind of the law of attraction, isn’t it?”

“This is what the Buddha says: what you think, you become. So if you fill yourself up with positive energy, then you know the positive things will come to your life.”

The celebrations continue for 16 days in total, concluding with a light-offering ceremony. Visitors place lit candles, symbolising clear-mindedness and wisdom, at the base of the Buddha statue. The candle, “is to light up your own life”, says the Venerable. “Buddha doesn’t need that offering from you, because Buddha is already enlightened, right?”

There is no singular way to mark lunar new year, but food is a fixture of many celebrations. At Nan Tien, Buddhist visitors typically won’t eat until noon, after a food offering has been made to Buddha, but the Venerable says in the interests of inclusivity and hospitality, vegetarian food is available to visitors from 10am. “A lot of people that come to the temple, they are not Buddhists … Maybe they’ve just come for the first time in their lives, [to] see what it’s like.”

In Sydney’s inner-west, university student Nina Nguyen skips breakfast – “it’s just too chaotic in the morning” – anticipating the long lunch she will co-host for her extended family.

Nguyen was raised Catholic, though she no longer practises. Compared to Christmas, lunar new year resonates more strongly with her identity as a Vietnamese Australian.

By 1pm, the Marrickville home she shares with her brother, father and grandfather becomes a multi-generational hub of activity. Children playing on the floor, cousins chopping ingredients in the kitchen; her brothers are “smashing up the ice” in the back yard while uncles cradle Coronas, “gathered around talking shit”. Nguyen’s father – who migrated to Australia from Vietnam in the 90s – sets up the outdoor wok-burner. His “pride and joy” dish is lobster XO noodles.

Everyone dresses in red. “It’s for the aesthetic, for the photos,” says Nguyen. “Also it makes us feel more connected when we’re dressed in the same colour.”

By 2.30pm, the feast will be laid out on red-clothed tables: platters of sashimi and oysters, fried crab claws, chicken feet salad, crisp roast pork belly, and bánh cuốn (rice noodle rolls filled with pork mince).

To drink – tequila. “Previously we’d go through Hennessy and Martell and right now we’re into our Don Julio phase,” says Nguyen.

After lunch the family plays Vietnamese traditional games including lô tô (similar to bingo), and bầu cua cá cọp, a novelty gambling game with dice and coins, and “lots of yelling and screaming”.

When the families with children have gone home, Nguyen and her brothers’ friends come around. “They’ll come expecting to eat but somehow get lured into drinking.” The party wraps by 10pm so Nguyen’s grandfather can go to bed.

Khoo has fond childhood memories of celebrations in Malaysia, where he was born. “[It was] family time: eating, bonding, drinking, gambling, fireworks, red packets, getting new clothes – all that stuff.”.

But his first lunar new year in Australia was anything but festive. Khoo and his brother moved to Sydney as teenagers for their high school education – without parents or extended family to celebrate with. “I felt very sad and depressed … I had PTSD from that first new year,” he says.

It’s why Khoo feels a responsibility to go all-out at his restaurants with a lion dance, and a luxurious seafood-heavy menu, where the yee sang lo hei (prosperity toss salad) is the headline act.

His celebrations at work and home are a way of honouring his late amah (Khoo’s paternal grandmother), the family matriarch. Growing up “she was the one doing all the work, she was the one doing all the cooking. She [got] enjoyment from serving others,” says Khoo. “That’s how my Chinese new year has evolved, from enjoying it as a kid to now wanting to provide that enjoyment to other people.”

Nguyen’s celebrations also make her proud of her heritage. It fortifies her sense of community with her Asian Australian friends who celebrate. More than any other day, “lunar new year is … special to us”, she says. “Because it’s like our own holiday.”