Subscribe to the BoF Podcast here.

As curator-in-chief of the Anna Wintour Costume Centre at the Metropolitan Museum, Andrew Bolton has long had the power to shape the fashion conversation with the exhibitions he creates. “Savage Beauty,” 2011′s scorching celebration of Alexander McQueen, is still the most famous; “Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and the Catholic Imagination” (2018) was the most popular, with 1.6 million visitors; and “Camp: Notes on Fashion” (2019) the most zeitgeistlich.

It’s always all about the zeitgeist with Bolton. He insists he cares less about mounting blockbusters than he does about making something that will have a timely emotional resonance with museum goers. One of my enduring memories of the McQueen exhibition is the middle-aged couple from Honolulu I met in the massive queue that snaked around the Met and into Central Park. They knew nothing about fashion, not much more about McQueen, but they’d been drawn by the promise of heartfelt engagement with a story whose rockstar ingredients — young genius whose life was tragically truncated — have proved irresistible time and again.

When I talked to Bolton in Paris recently for The Business of Fashion’s latest podcast, I asked him whether he thought there’d be a similarly transcendent mass appeal to the subject of his latest spectacular, “Karl Lagerfeld: A Line of Beauty.” True, Lagerfeld had a peculiar rockstar gloss with his omnipresence, his avatar-like image (Met Ball attendees should have fun with this one) and his groovalicious retinue, but there seemed nothing but a life fulfilled, on the surface at least, in the saga of a polymath who died at the age of 85 after more than six decades of success as a designer.

“It’s the mystery of Karl,” Bolton suggests. The mystery of a man who consumed life at a furious pace at the same time as he insulated himself from quotidian human dramas, drolly observing the passing parade from behind his impenetrably dark signature shades. What was he protecting? Bolton wondered. He claims he was shocked by the vulnerability he saw in Lagerfeld’s eyes on the rare occasions he wasn’t wearing sunglasses. “But I didn’t want to get into that rabbit hole of trying to sort out what was truthful in his life and what wasn’t,” he says. “I thought the one thing that was authentic, that was real and tangible, was his creative output.”

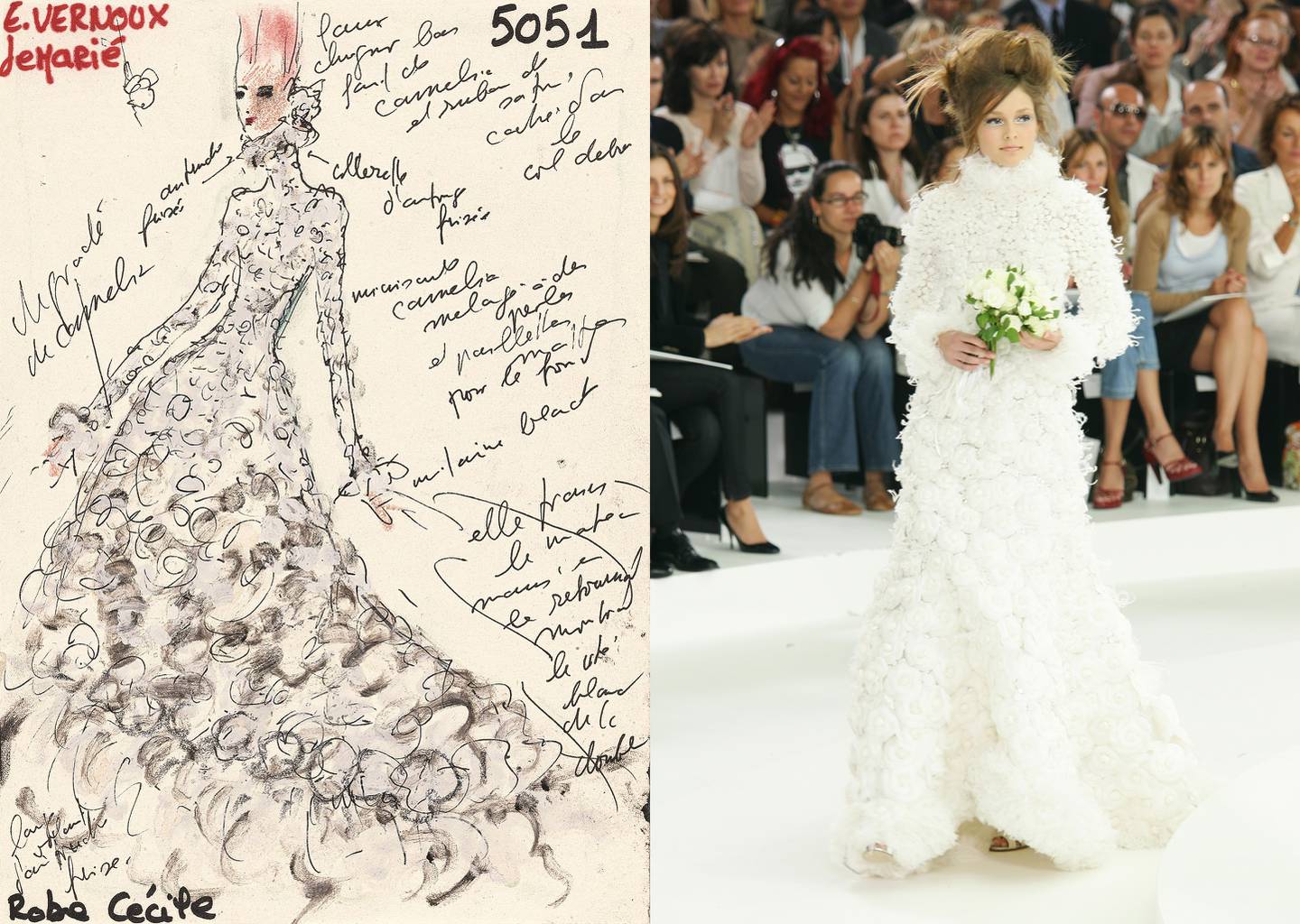

So the exhibition is solidly focused on Lagerfeld’s work, for Chloé, Fendi, Chanel, his own label, all the tributaries which helped create what Bolton calls “the blueprint of the modern design impresario.” The line of beauty could refer to the creativity that elicits order from chaos, and it would be hard to find a more zeitgeistlich notion than that right now, but it is, in fact, a direct reference to Lagerfeld’s hyper-linear sketching technique. He was often drawing while you were talking to him. Picasso would do something similar with his lunch guests, then, at the end of the meal, ask if anyone wanted to buy his drawing. If there were no takers, he’d rip it up. Lagerfeld never offered, and I certainly never plucked up the nerve to ask him for the sketches he’d make during our conversations. What happened to them all? That’s another mystery, and not one that’s likely to be solved by the show.

Still, Bolton promises surprises for those who care to delve, even if his exhibition concentrates on Lagerfeld’s creative process, rather than any juicy autobiographical marginalia, “I always felt Karl’s clothes were confessional,” he muses. “They were his own psychoanalysis.” His greatest consolation, even. And that constitutes revelation when you’re dealing with a man whose relentless decades-long coverage would suggest there was precious little left to say. “You end with this jigsaw puzzle that invites the audience to put it together as a whole,” is Bolton’s fervent hope. And who hasn’t found jigsaw puzzles a curious balm in these fractured times?