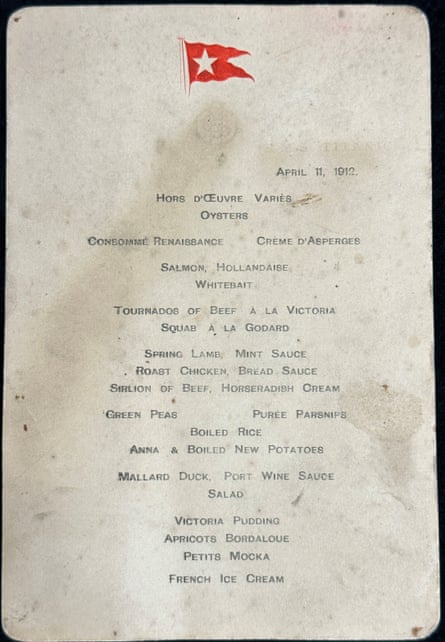

It was not quite the last supper for the first-class passengers on board RMS Titanic, but very nearly. A unique surviving ship’s menu from 11 April 1912, going under the hammer this weekend, has revealed the treats that were served on the doomed liner just three days before it hit an iceberg on its maiden voyage across the Atlantic.

Expected to sell for up to £70,000, the bill of fare poses some interesting questions: among them, who grabbed a menu while making for the lifeboats, and what is Victoria pudding?

The second is more easily answered. The boiled dessert, which was offered accompanied by apricots and French ice-cream that evening, is made by mixing flour, eggs, jam, brandy, apples, cherries, peel, sugar and spices. On 11 April, it followed oysters, salmon, beef, squab, duck and chicken, served with potatoes, rice and parsnip puree; dishes all listed on a water-stained card beneath a White Star logo.

The menu details the meal served the day after the ship left Queenstown, Ireland, heading for New York, and is being sold by Henry Aldridge & Son of Wiltshire, alongside other rare Titanic lots, including a tartan deck blanket. The menu was found in a photo album from the 1960s that once belonged to Len Stephenson, a community historian in Dominion, Nova Scotia.

Andrew Aldridge, manager of the auction house, believes that while a few other first-class menus survived the wreck that led to the death of 1,500 people, none for this evening are known. “I’ve spoken to several museums globally, and I’ve spoken to a number of our Titanic collectors,” he said, “I can’t find another one anywhere.”

At auction, Titanic mementoes fall into broad categories, each with different status. Some were recovered from the wreck, some are owned by survivors, and some, like the opulent dinner menu for 11 April, are likely to have been removed from the ship as keepsakes.

For Harry Bennett, an associate professor of maritime history at the University of Plymouth, items thought to have been recovered from the bodies of victims were particularly disturbing and raised “a question of personal morality”. “These things are really probably better in museums than actually in private hands because it at least creates a kind of a context for it where issues of profit are rather taken away from it,” he told the New York Times this weekend.