Welcome to the Krampusnacht edition of Shock of the Old! I hope you’ve brought your horse skull, horns and whip. If you’re imagining delighted children, jolly gifts and gingerbread, you’ve come to the wrong column: ’tis the season of ineffable terror (yes, ha ha, just like your family Christmas). In European folklore, Krampusnacht, or Krampus Night, falls on 5 December, marking the arrival of Krampus, a half-goat, half-demon that punishes naughty children during the festive season.

Scrolling through pictures of shadowy, ragged, often armed seasonal figures, I’ve been wondering why European winter folklore is so chilling. Why do “season’s greetings” in some parts mean “watch out for the witch with the large and misshapen goose foot – she’ll slit your belly open and stuff it with straw”? It’s fascinating how it’s a time of dread as much as celebration: in Serbia, the 12 days of Christmas were considered “unbaptised” time, when demonic forces were at their most powerful and all sorts of awfulness – yes, worse than braving the Next sale queue on Boxing Day – might happen to the unwary.

I’ve had time to think about this, because I spent 12 years in Belgium, where early December is a time of awful reckoning for under-10s, thanks to the menace of St Nick’s sidekick, the cheerily named Whipping Father or Père Fouettard (Black Pete or Zwarte Piet in Dutch). He hasn’t just been making a list and finding out who’s naughty or nice – he truly lives up to his name. And that’s before we get into the apparently not racist tradition of blacking up to represent him at festive events in Belgium and the Netherlands (because nothing says “not racist” like obstinately sticking to a custom that people have told you they find racist, hurtful and offensive).

It’s hard to trace a clear history for these terrifying traditions. They are a hazy glühwein-fuelled amalgam of pagan, medieval Christian and counter-reformation, plus goodness knows what weird Alpine village lore, but you can see why they were popular. At this time of year, children are … how can I put this? Annoying. Hysterical, demanding, loud. In the days before Bluey and Nintendo Switch, getting a few minutes’ peace during a long, dark winter stuck at home was vital, so traditions emerged offering a reward for good behaviour or an awful punishment for bad, delivered by a nightmarish figure. You better watch out, you better not pout, because, well. At the lower end of the tariff scale of punishment, one German custom says the angry chimney sweep Knecht Ruprecht will “hit you with his bag of ashes”, which seems small fry in comparison to some others. Speaking of bags, if there’s a sack involved, you’re probably going in it, maybe to get thrown into an icy river. Worst case scenario, the Krampus will eat you – he’s basically a goat and goats eat everything.

This makes Père Fouettard, Schmützli, Krampus et al seem like proto-elves on the shelf – a theory Jacob Grimm aired in 1835, describing the festive figures as a version of the pre-Christian “house spirit”. But rather than being toothless narks for Santa, they take matters into their own hands; violent yin to his jolly yang. It’s a peerless behaviour-modification strategy, until the nightmares start.

Time to climb on my knee and open this bulging sack of photographic horrors. I hope you’ve been good this year …

Saint Nicholas, circa 1503-1508

If you don’t know the St Nicholas story, you probably think this picture (from Anne of Brittany’s Book of Hours) depicts a kindly bishop teaching a swimming class for exceptionally ripped children, one of whom looks an awful lot like Matt Hancock. Actually, the saint is admiring his handiwork after miraculously reconstructing these kids, who had been chopped up and pickled by a naughty butcher: a jolly start to our festivities! Note the man in the background who has decided whatever this is, he isn’t getting involved.

Krampus and child postcard, 1900

This is less kid on Santa’s knee and more kid on Satan’s knee – though, to be fair, she seems happy enough. A German seasonal menace, the Krampus may be pre-Christian (although there’s no actual evidence of this), but has long been associated with the devil, what with the horns and general malevolence. Either way, I don’t see him picking up many shifts in the John Lewis grotto.

Perchten parade, 1890

While the 19th-century Perchten festival – an Austrian seasonal demon-driving-out event – does look debauched (and eerily reminiscent of UK mainline stations on Christmas Eve), I urge you to seek out pictures of contemporary parades, which are even worse. If you’ve ever yearned to be harassed by a half-haystack, half-monstrous goat, you know where to go (Austria).

Greetings from Krampus, undated

The standardised Krampus “look” – black, horns, ridiculous tongue – only took hold in the late 19th and early 20th century, when exchanging these cards became a seasonal tradition. Some merry etymology: likely derivations of Krampus are either krampen, German for claw, or the Bavarian krampn meaning dead or rotten.

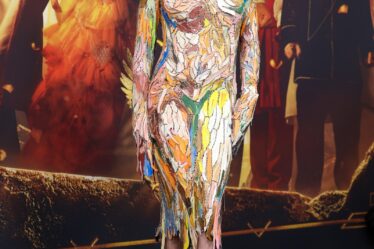

Peruchty, 1910

It’s nice to know seasonal horror can also come in female form. This is a Bohemian iteration of Perchta, an exceptionally horrid winter witch, with a misshapen goose’s foot and a taste for disembowelling naughty children. In the 15th century, the papacy condemned those who left her offerings.

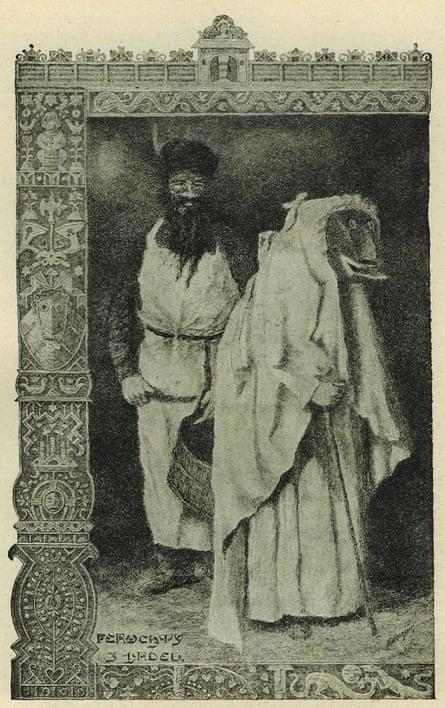

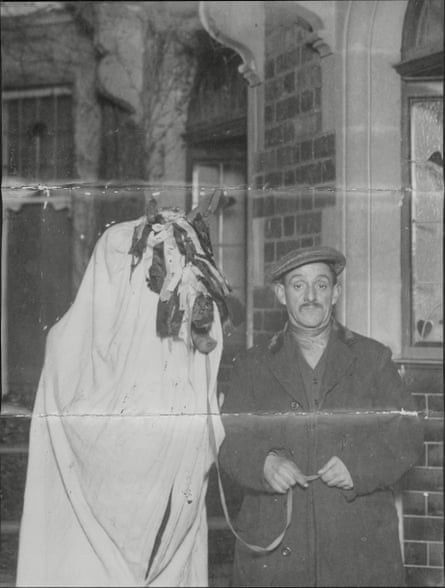

Mari Lwyd, 1921

Mari Lwyd sounds like a 60s singer your grandad had a crush on. But no, it’s a Welsh folk custom whereby a horse’s skull is mounted on a pole, and covered in ribbons and a sheet (under which its operator hides). The Mari Lwyd prances around villages, singing, biting and demanding food with menace. You might enjoy a 1966 BBC Wales documentary in which three smartly dressed, sombre men escort a Mari Lwyd to perform a haunting dirge outside some unfortunate’s door. You’d rather sleep tonight? Fair enough. The earliest written record of the tradition dates from 1800 but it, too, might have pagan origins. Where are they getting all these horse skulls? No, don’t tell me.

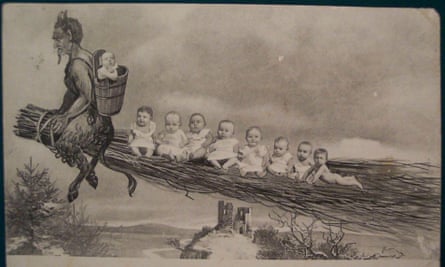

Krampus takes the children, undated

This not-so-scary Krampus looks like a put-upon Mr Tumnus from CS Lewis’s Chronicles of Narnia books, his sweet little hooves and tail dangling as he whisks nine children away on his broomstick. There’s a Kindergarten Cop-style feelgood Christmas movie in this.

Saint Nicholas and helpers, 1935

An examination of St Nicholas’s relics in 1957 revealed that he was of “slender-to-average build”, probably vegetarian and suffered “severe chronic arthritis” and headaches. So it’s hard to imagine him enjoying hanging out with this entourage of exhausting-looking wrong ’uns , probably “tuifl” (devils) from Tirol, western Austria. Their vibe is part Where the Wild Things Are, part the kind of seasonal lads’ night out that ends up with someone vomiting into a Santa hat on the Piccadilly Line at 11:45pm.

Hans Trapp, 1953

Hans Trapp, also known as Hans von Trotha, actually existed – he was a 15th-century knight who fought with some monks and petulantly flooded a town – but gets conflated with Knecht Ruprecht and Père Fouettard in parts of eastern France when it comes to seasonal child-scaring. The picture itself is low on terror, but as Chekhov didn’t exactly say, if you bring a whip to act one, you better be chastising children with it by act two.

Mummers at Brick Lane market, east London, 1966

It’s nice that England has its own festive folk horror in the form of the mumming play, or, in this case, morris dancers that someone has put through a shredder. Mummers were originally bands of masked people who paraded the streets during winter festivals. Mummer plays probably had pagan origins, and are definitely ancient; they were already a traditional Christmas celebration at Edward III’s court in the 14th century. I like the one who has decided to give up and have a lie down (OK, he’s probably the character who traditionally gets killed in a swordfight); many of us will be that horizontal mummer at some point this month.