Images and Article from www.theguardian.com.

It had been 20 years since I’d seen my aunt. In that time I’d lived a full life, written a book and had a baby, but as she stared at my bottom, I knew what she was thinking. Then she said it: “Are you competing with Mary?” There was some skill here: in a few words, she’d deftly managed to insult both my cousin and me. The subtext was: you’ve got as fat as her.

Fuelled by post-partum hormones, I decided to tell my aunt, for the first time, how insulting I found this. “I’m sorry,” she said, “if you chose to take offence at what I said.” Ah. The apology rendered immediately void by the word if.

Expecting any apology at all was ambitious, because I come from a family who largely can’t and don’t apologise (strange, given we are all Catholics). The sorrys are either histrionic and overplayed, or never manifest – the idea being, I guess, that if you don’t say sorry, did it even happen? I’ve also always been confused at the very English “never apologise never explain,” maxim, supposedly a sign of status. Because of all this, I’ve had a lifelong fascination with apologies, and a lot of them, including my own, are sometimes lacking. Why is this? Why is it so hard to say sorry?

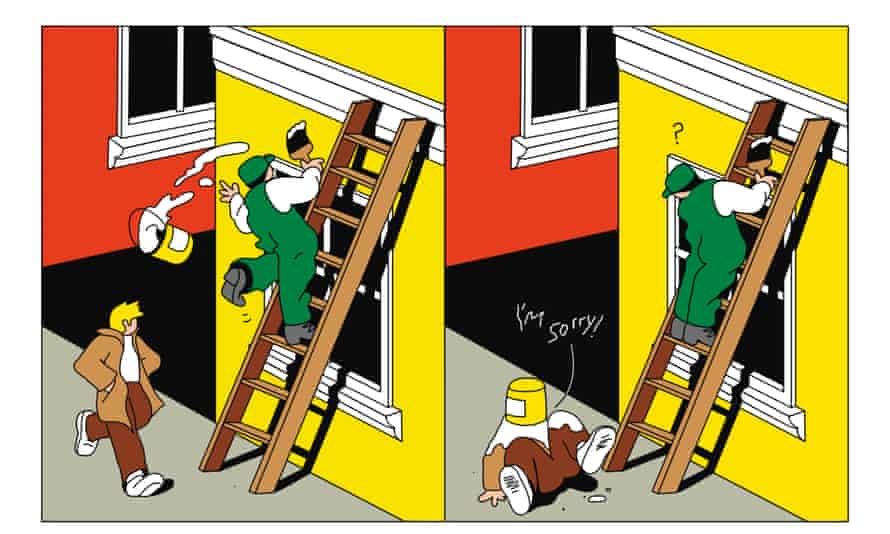

There are several types of apology. The automatic “Sorry I bumped into you”; the “Sorry, after you” in a queue; and the very British sorry for someone else’s misdemeanour, like when they stand on your toe. We say a lot of these silly sorrys. There’s also sorry said in sympathy or sorry to sympathise: “I’m sorry to hear that” or “I’m sorry: that sounds hard.”

But the sorry that matters is the one aimed at healing hurt – when we recognise we’ve done wrong and want to make amends. This is not an easy sorry. It requires more than mere vocabulary, which is why teaching children to say sorry by saying “Say sorry” is not a robust parenting tool. The ingredients for a good apology are: authenticity, recognition, empathy, ability to take responsibility, and, finally, a good dose of vulnerability and humble pie. It’s a grownups’ word, yet few grownups use it well.

If it lacks these things, it doesn’t “land”, said child and adolescent psychotherapist Alison Roy. This is why we so often feel short-changed after an apology, especially an official one: we were wronged with the original fault, and wronged again in the supposed apology. In fact, we can end up feeling manipulated. Corporate-speak is now so clever: we are apologised to with such regularity, yet never feel anyone has really said sorry. Train companies: I’m looking at you.

“An apology has to be meaningful if anyone, but especially children, is going to make sense of it,” said Roy. “It should be a way to reconnect [with the person you’ve wronged]. But coping with feelings of shame, of having got something wrong, of being a flawed human being, is quite a sophisticated thing. These are not easy emotions and experiences, so we can’t just expect our children to understand by giving them a word. We have to model it for them.”

In other words, we need to practise what we preach. It’s important to start with children because it is usually in childhood that most of us learn to say sorry, or not. It tends to be either modelled well, or not at all. We realise how it leaves us feeling – wretched – and resolve to do better.If we learn to say sorry without thought, all we learn is that sorry is a quick way to get off the hook. There’s no reflection. This often leads to an apology with no change in behaviour, which is pointless and infuriating. And forcing anyone, especially a child, to say sorry to an audience without first finding out what happened can lead to resentment and humiliation: never good in a growing brain.

I once taught a writing workshop in a secondary school. One day I did something wrong and said: “Gosh, I’m so sorry.” The class fell silent. “Teachers never say sorry to us, miss,” they told me. This is a common lament among young people: “Adults expect us to say sorry but they never do.”

You have only to listen to debates in parliament to tell the good apologies from the bad, and hear how very “playground” some of them sound. In the past 12 months there have been 1,812 “I’m sorry”s from both houses, and counting (the House of Commons tips the Lords at 1090/722), and 1,273 “I apologise”s. Most of these are mere punctuation, and in the case of Boris Johnson, even when he does apologise – and he apologises more than people think – and uses good phrases such as “I take full responsibility” and “I am truly sorry”, it just doesn’t “land”. I often wonder how Johnson was taught to apologise as a child.

It’s rather shocking how many of these apologies try to shift the real responsibility: “I’m sorry” followed by a conjunction (if/but/that). Examples include: “I’m sorry that you feel that way,” and “I’m sorry if you took offence.” Familiar, aren’t they? That’s because they are everywhere. Hansard is full of things like, “I’m very sorry to the noble Baroness … that she feels that way.”Is that really being sorry?

“It’s the worst kind of apology,” said mediator and conflict resolution expert Gabrielle Rifkind. “Saying ‘I’m sorry you feel that way’ is not a genuine apology. It’s not taking responsibility for your actions; it’s putting the blame back to [the wronged person].”

Sign up to our Inside Saturday newsletter for an exclusive behind the scenes look at the making of the magazine’s biggest features, as well as a curated list of our weekly highlights.

Rifkind once gave me a wonderful tip about building bridges. It involved starting with words to the effect of: “You really matter to me and I want to work out what has gone wrong, so I’m going to do nothing but listen to you for the next 15 minutes.” When was the last time someone said that to you? Exactly, but it’s seductive isn’t it? I’m not sure I would even need an apology with that sort of starter.

But it is hard to apologise if we fear reprisals: fear and shame are the enemies of a confident apology. To bloom, apologies need safety and the prospect of being understood. Safety is often lacking because we fear that saying sorry could cost us our relationship, our job or a heap of money. One of the things we’re taught as new drivers is “don’t admit fault” if there’s an accident, even if it is your fault.

Psychoanalyst Stephen Blumenthal thinks authentic apologies are more likely in “horizontal, more democratic relationships” – if the person saying sorry and the person wronged are on the same level – than in a more vertical relationship such as boss and employee. This is why siblings and co-workers are more likely to admit to wrongdoing to each other than to parents or bosses, unless of course, they fear being ratted out.

“A genuine sorry,” he said, “emanates from a place of wanting to validate and care for the other person, not shame them. We live in a culture of inquisition rather than inquiry, more concerned with identifying a person with an action [of wrongdoing] than curiosity about what’s gone wrong or why.”

Some people see it as a sign of power to not say sorry. But the inverse is true. At some point I realised that a good apology, confidently delivered, was like having a superpower. Even something short like “I got it wrong – I’m sorry” can be potent and calming. Or, if you want to go longer: “I can see I’ve upset you and I’m very sorry. I made a mistake. It won’t happen again. What can I do to make it a bit better for you? What do you need?” Notice the use of the “I” word, and “you” only in terms of needs. It isn’t an apology if you shift the blame.

One of my favourite apologies of all time was given by former MP Louise Mensch in 2011. She not only owned her behaviour and apologised, but killed any further discussion stone dead. She’d had an email from an investigative journalist accusing her of taking drugs, being drunk and dancing with a famous violinist, all “in front of journalists”. It was done to shame her. Instead of running away from it, she published the email, adding that the incident sounded “highly probable” and that she was pretty sure it was not the “only incident of the kind”. She apologised “to any and all journalists who were forced to watch me dance that night”. A little bit of humour did her no harm, but the power was in her ownership of the incident, leaving no ammunition with which to take further aim at her.

Sorrys are not dissimilar to thank-yous. Both are small but mighty. So much grace and joy can be handed over if you use them with meaning, and they can both deliver much misery and hurt if misused, or not used at all.

Sometimes, however, people make an apology but it comes too late or is too small, and it can feel hard to accept or move on. Questions to ask yourself here would be: instead of making the sorry the end of something, could it be the beginning of a bigger discussion, along the lines of, “What do I need to do to make it better?” or “Can anything make it better?” If the answer to the latter is “no”, perhaps the sorry is being asked to do too much heavy lifting right then. Time may be needed for healing. But can it start without sorry? I don’t think so.

I’m writing a series of children’s books. One is about saying sorry: the protagonist fears that every time they do so, a piece of them goes with the apology and they will lose themselves. The opposite is true – with every genuine sorry, we grow, the other person grows, and so does the connection between us.

Series two of the Conversations with Annalisa Barbieri podcast is out now

Article shared from www.theguardian.com