As the fashion industry races into a digital future, the schools training its next generation of workers are hurrying to catch up.

The presence of emerging technologies in fashion curriculums has at times proved scattered and uneven. While there are some schools taking up the challenge, many still have not.

A recent survey found only five of the eight top fashion schools looked at included 3D design — perhaps the most common new skill students are learning — as part of their core curriculum as of October 2021, according to Peter Jeun Ho Tsang, who worked with IFA Paris to create its MBA in fashion tech and is the founder of Beyond Form, a venture studio specialising in fashion and technology that partners with startups to launch their businesses. One of Tsang’s students conducted the research.

The reasons for the delayed uptake of the latest technologies can vary. Some tradition-minded schools can be slow to embrace new ways of working, and cutting-edge tools can require costly upgrades to equipment. Updating a curriculum can be a drawn-out process, not to mention risky if it involves technologies that might become quickly outdated.

But a shift may be underway.

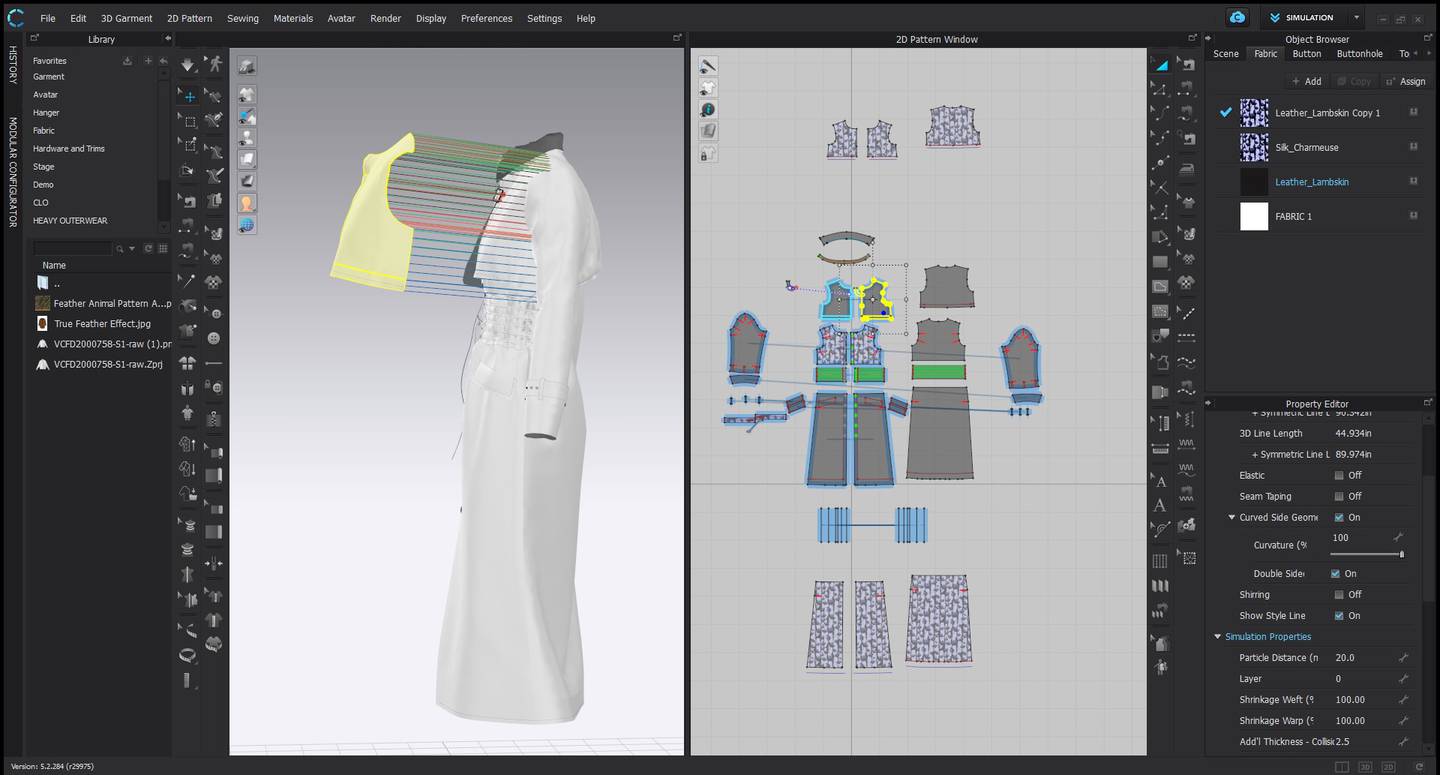

Parsons in New York has begun teaching the 3D-design tool Clo3D to all students beginning in their third year after running trial courses in 2019 and 2020. The Institut Français de la Mode (IFM) in Paris said advanced training in Clo3D is now part of its curriculum for all design and pattern-making students as well. It also offers a six-month programme on “virtualizing” the value chain, from material design through marketing, and a master’s degree in fashion management with courses covering data science and analysis.

At IFA Paris, along with training in traditional skills like pattern cutting by hand, first-year students all learn to design digital clothing in tools such as DC Suite. Going into their second year, they cover prototyping — “so 3D printing, laser cutting, body scanning,” said Tsang. The MBA programme, meanwhile, gives students the opportunity to learn programming and artificial intelligence.

“Things are changing — they’re changing quite rapidly,” said Matthew Drinkwater, head of the Fashion Innovation Agency (FIA) at London College of Fashion. “You can see across the scope many schools now beginning to offer courses specifically in digital fashion.”

Graduates of these programmes are entering a job market where fashion companies increasingly value skills such as data analysis and proficiency in 3D tools but often turn to other industries to fill those niches. Levi’s, for one, recently formed its own AI bootcamp as a way to create an internal talent pool after first hiring data scientists from fields like tech and finance. Students may also launch new businesses, or find their way to outside industries like gaming where a knowledge of fashion is valuable. The point isn’t just to ready them for roles in fashion but also to enable them to carry fashion forward.

New Opportunities

The fashion industry’s ongoing digital transformation has many companies steadily, if still sometimes slowly, looking to technology for a competitive edge. On the business side of operations, more brands and retailers are seeking employees comfortable working with the troves of data they’re collecting online to inform decisions on everything from marketing to product development. In the case of 3D design, big labels such as Adidas and Tommy Hilfiger are already using it widely in their businesses, and as more companies adopt it, the more in-demand those skills will become.

“There are a lot of job opportunities for [students] in that space,” said Amy Sperber, an assistant professor of fashion design at New York’s Fashion Institute of Technology (FIT). “There’s product development with the tool. It’s a great tool for sampling. It’s a great tool for the production line. We’re also getting requests for students to work with people that are utilising the 3D outputs in totally different ways.”

Brands are also using 3D assets in their e-commerce or social media, she noted. And then there are uses still emerging, such as virtual fashion.

In 2021, Ravensbourne University London launched what it calls a first-of-its-kind course on digital technology for fashion. Eligible students who enrol learn skills such as modelling digital avatars, virtual garment design and how to create immersive virtual-reality environments.

“I knew that there would soon be a merging of worlds between gaming and fashion design and I pushed Ravensbourne to embrace this opportunity,” said Lee Lapthorne, programme director of the school’s department of fashion.

His prediction is bearing out as more brands tap into the huge and valuable gaming market.

Alexander Knight, who studied fashion design at Ravensbourne and quickly switched to learning digital design when the pandemic interrupted in-person activities, has begun selling virtual garments through DressX, a virtual-fashion startup. He also freelances for another company to digitise their real-world designs. In his experience since graduating in 2020, companies are just starting to look for proficiency in 3D tools when hiring, but he said the demand for digital capabilities is picking up.

“It’s where everything in life is headed,” he said. “Courses need to start teaching it in order to give their students skills that are going to be useful for the future of fashion.”

Obstacles

Even if fashion schools want to integrate new skills into their course of study, they can find it slow-going.

“It’s a two-year process for our curriculum development,” said Sperber.

At FIT, 3D design is still taught as an elective rather than a core skill. Sperber said the pandemic made it “very obvious” FIT couldn’t delay any longer in teaching students 3D, but because it’s a state school and receives public funding, its curriculum has to go through a rigorous review process. Costs are an obstacle too. After introducing 3D design, FIT quickly realised it didn’t have the right graphics cards in its computer labs.

“It requires purchases of hardware, software,” Sperber said. “We’re not talking one machine. We’re talking thousands of machines.”

And there’s no guarantee every cutting-edge tool will become the standard. Students inspired by the metaverse boom to focus their studies on designing for virtual reality could find themselves at a disadvantage if the hype doesn’t pan out.

Running courses as electives “enables us to be very agile in how we respond to emerging technologies,” Drinkwater said.

FIA operates as a creative consultancy in partnership with the fashion and tech industries. It then brings technology to digital learning labs it conducts at London College of Fashion.

It has held courses on artificial intelligence where students learn to code in Python and get access to tools like a photogrammetry rig, which uses dozens of cameras to produce intricate 3D renderings of an object or model. Students can use the 3D assets in virtual experiences they make with game-creation engines such as Unity or Unreal, which is what Balenciaga used to create its Afterworld game and its Fortnite collaboration.

These skills may not currently be needed by every fashion brand or retailer. But Soojin Kang, interim co-director of the fashion MFA programme at Parsons, said teaching students new technologies is also important to prepare them for what’s on the horizon. She pointed to the metaverse, NFTs and the ongoing growth of different digital assets. And these aren’t the only reasons she believes it’s important to give students the best technological tools.

“It’s not just about the industry,” she said. “Once you found a better way, why do you want to go backward?”