If you’re a millennial or have parented one, you know the look: advertisements with shirtless men, sculpted abs above low-cut jeans, a melange of thin and tan and young white bodies in minimal clothing. A store at the mall mostly obscured by heavy wooden blinders, music pulsing from within. Faded jeans and polo shirts in middle and high school, all featuring the ubiquitous moose.

White Hot: The Rise & Fall of Abercrombie & Fitch, a new Netflix documentary on the ubiquity of a once zeitgeist-y brand’s limited vision of “cool” and its culture of discrimination, is easy catnip for adults re-evaluating the influences of their youth. The brand of barely there denim miniskirts and graphic T-shirts was “part of the landscape of what I thought it meant to be a young person”, the film’s director, Alison Klayman, told the Guardian. (Klayman, a millennial, grew up in Philadelphia.) That’s true for many US adolescents in the late 90s through the 2000s, as Abercrombie stores anchored most mainstream malls across America, including my hometown middle school hangout in the suburbs of Cincinnati, Ohio.

Anytime Abercrombie comes up in conversation, “you immediately cut right to stories about people’s identity formation”, said Klayman. How much money you could or could not spend on clothing, body insecurities, memory imprints from hangouts at the mall. The overpowering smell of its cologne, Fierce, liberally applied to every surface. The messages one received on what was cool, on whose bodies met the right standards and whose did not.

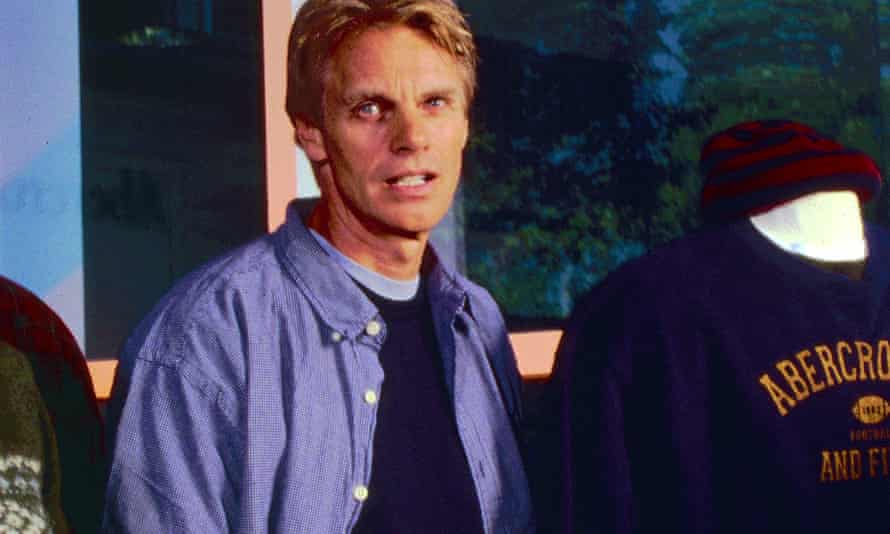

As White Hot traces through a succinct and wide-ranging survey of the brand’s evolution and sales tactics, Abercrombie & Fitch, a company hinged on a vision of “preppy cool”, kept those messages pretty overt. To quote former CEO Mike Jeffries, who oversaw the brand’s precipitous rise in the late 90s and 2000s, in a now infamous interview from 2006: “We go after the cool kids. We go after the attractive all-American kid with a great attitude and a lot of friends. A lot of people don’t belong [in our clothes], and they can’t belong. Are we exclusionary? Absolutely.”

Translation: a brand that was “white hot” not only in a financial sense, during a period of cultural ubiquity at the turn of the millennium, but also one that promoted, internally and externally, an exclusively white vision of beauty and style. That “all-American” is doing a lot. (The brand also famously refused to carry plus sizes for years, until after Jeffries departed in 2014.) As White Hot recounts through first-person interviews with several former staff members and cultural academics, this is a brand that once sold graphic tees branded with a racist depiction of Asian people and the words “two Wongs can make it white”. The brand that, in corporate materials, banned store staff from having dreadlocks, that ranked employees on appearance and skin tone, faced a class action racial discrimination case in the early 2000s and argued before the supreme court in 2015 that it was legal to deny employment to a woman with a headscarf because the religious garment violated its “look policy”. (The company lost in a 8-1 ruling.)

The 88-minute film offers its fair share of nostalgia bait – the opening sequence plays alongside Lit’s My Own Worst Enemy, and the signature scent is subject to plenty of good-natured ribbing – but focuses on taking scalpel to the company’s finely tuned, if now stale, image. “We wanted to focus on the everyday people who were affected by this company,” said Klayman.

Taking a more objective look at Abercrombie offered the opportunity to examine “abstract forces that impact us in life, things like beauty standards or structural racism”, and peek behind the curtain to see “exactly how this was a top-down system that relied on existing biases”.

That system, the film explains, was both a reflection of American culture and executed under the exacting watch of Jeffries, who took over as CEO in the early 1990s. The Abercrombie & Fitch name was established (as the shirts often boasted) in 1893 as an elite sportsman’s store (think a Teddy Roosevelt-esque gentleman hunter). It became the famous moose polo version after retail magnate and Jeffrey Epstein financier Les Wexner purchased it, moved its headquarters to Columbus, Ohio, and handed the reins to Jeffries.

It was Jeffries – a mercurial and reclusive figure who declined to participate in the film – who masterminded Abercrombie’s transformation into a clothing brand that united Calvin Klein sexy and Ralph Lauren Americana, sold at aspirational but accessible prices, marketed primarily to adolescents. Jeffries was, by numerous accounts from former corporate employees in the film, demanding, obsessed with youth and a micro-manager who emphasized appearance – as in, thinness, whiteness and Eurocentric features – at the company’s stores. In 2003, under Jeffries, the company faced a class action racial discrimination lawsuit from California which alleged that the company turned down minorities for sales positions, relegated them to stockrooms, and had their hours reduced when managers heard their looks weren’t Abercrombie enough. (Three of the class-action plaintiffs testify to such discrimination, and its emotional damage, in the film.) The company settled the lawsuit for $50m without admitting wrongdoing.

As part of the deal, Abercrombie & Fitch was subject to a consent decree and required to hire a diversity officer – Todd Corley, who appears in the film but defers from revealing his full opinions on the brand’s controversies. As White Hot explains, the consent decree had no enforcement mechanism, and though representation increased behind the scenes, the brand’s exclusionary vision under Jeffries continued. “Discrimination was their brand,” says Benjamin O’Keefe, who started a viral petition to boycott the brand in 2013 until they made their clothing for teens of all sizes. “They rooted themselves in discrimination at every single level.”

Jeffries certainly meets the “eccentric bad CEO” criteria now popular in TV shows, from WeCrashed to The Dropout to Super Pumped, and its depictions of millennial hustle culture (“Abercrombie was definitely doing work hard, play hard,” said Klayman.) But as titillating as it can be to focus on his oddities (his comically exaggerated plastic surgeries, for example), such focus can end up being “exculpatory”, said Klayman. “It kind of lets all of us, the collective, off the hook, not to mention the entire company that was facilitating this exclusionary vision for decades.

“It’s really convenient to put all the sins on Mike [Jeffries] and that era because he was so closely associated with the company’s rebirth in the 90s and early aughts,” she said. “And he definitely deserves real criticism, but it takes more than one guy to do what A&F did.”

Since Jeffries left in 2014, the company has changed tack. Under CEO Fran Horowitz, appointed in 2017, the company’s sales have rebounded from its mid-2010s nadir and a rebrand of its image to one of inclusivity, one more in line with the politics of Gen Z. “We run a company very focused on diversity and inclusion,” Horowitz has said. The company has developed a cult following for its Curve Love jeans in a range of sizes.

Their marketing now “puts them in line with what good business looks like today”, said Klayman. But “it’s important to talk about it holistically, and I don’t know how much they’ve truly reckoned with their past”. That reckoning, the film ultimately argues, goes beyond a corporate rebrand; the brand was not so much exceptional as illustrative. It was not the pioneer of exclusivity nor whiteness but, for a time, one of the best at profiting on it – which, to be fair, is pretty classically all-American.