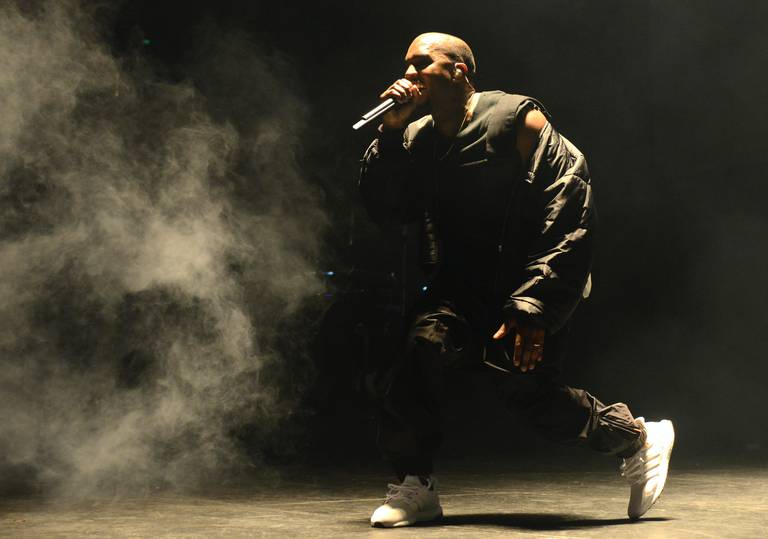

HERZOGENAURACH — When Kanye West took the stage at the 2015 Billboard Music Awards in Las Vegas, he was a shadowy silhouette in a fiery haze. For millions of people watching along on television, the first glimpse of the controversial American rapper was his sneakers: all-white Adidas Ultra Boosts popping through the pyrotechnics.

The all-white colourway with black soles had never been seen before in public. And though West’s performance lasted only 5 minutes and 18 seconds, it was enough to spark a frenzy among sneakerheads around the world that would ultimately send sales of Ultra Boosts soaring by 98 percent that year.

“After that day, every single pair of Ultra Boosts sold out. No one could keep them in stock,” recalls sneaker guru Yu-Ming Wu, founder of Sneaker News, a top resource on sneakers, and co-founder of Sneaker Con, the world’s biggest sneaker trade show. “This moment changed the game for Adidas. Kanye made the three stripes cool. That’s when the brand started to catch fire — and ultimately it became this wildfire that’s burning globally.”

But no single moment reflects the German sportswear giant’s recent success quite like the launch of its Adidas Originals NMD. The sneaker was first unveiled in late 2015. When it was re-released in additional colourways on 17th March 2016 in response to high demand, large queues (sometimes in the thousands) formed outside the company’s retail stores. The brand sold 400,000 units that day — and this without any major celebrity endorsement. “The NMD was another perfect storm for Adidas. In Shanghai, 5,000 people lined up at the Adidas Originals store — and they sold out worldwide,” recalls Wu. “Now almost everything Adidas puts out is cool.”

In the global market for sneakers, being ‘cool with the kids’ is a critical driver of business performance. The US accounts for about 45 percent of the $55 billion in worldwide sneaker sales, but only one-quarter of Americans buys sneakers for athletic use, according to research firm NPD. “Seventy-five percent of people buy sneakers because of their aesthetic and lifestyle features — and the younger you go, the more important footwear becomes. It’s the ultimate status symbol for kids,” explains David Fischer, founder and chief executive of influential streetwear and youth culture title Highsnobiety, which named Adidas “most relevant brand” in 2016, when it accounted for over 9 percent of all traffic to the Highsnobiety site. That same year, Adidas reported exceptional results, earning net income of more than €1 billion for the first time in its history. Critical to this success were sales of lifestyle items, which grew by 45 percent year on year.

It wasn’t always this way. Back in 2012, Adidas’ share of voice on Highsnobiety was below 2 percent, meaning the brand was decidedly uncool.

At the time, the cool kids wore Nike. “I would see what consumers were buying at Sneaker Con. The only sneakers people wanted were Nikes, especially Air Jordans,” remembers Wu.

Whereas other footwear brands are extremely protective of their DNA, Adidas is going the opposite direction with collaborations that are more open-minded.

2014 was a particularly miserable year for Adidas. Revenues linked to the World Cup should have buoyed sales, especially as the Adidas-sponsored German team won the tournament for the fourth time. Instead, two weeks after the final, the company issued a profit warning and walked back from its 2015 goals. At the time, Ingo Speich, a fund manager at Union Investment, a large investor in Adidas, called the company’s performance “catastrophic.” The stock price plunged by 16 percent. By the end of the year, Adidas had dropped to third place in the US market, falling behind Under Armour.

Something had to change. The company’s turnaround was the product of a deliberate strategy to re-energise its brand and reassert its place in culture.

“Two years ago, we presented our strategy ‘Creating the New’. The focus of this strategy was to significantly increase the desirability of our brands, because only with desirable brands can we sustainably grow sales and improve profitability,” explains Kasper Rørsted, chief executive of Adidas Group. “Our 2016 results are proof positive that ‘Creating the New’ is working. Focusing on our strategic choices ‘Speed’, ‘Cities’ and ‘Open Source’ makes us much more impactful in the marketplace compared to a few years ago.”

Open Source, Speed, Cities

“Open Source” may be the most powerful component of the strategy. It refers to a new operating principle rooted in openness and collaboration. Adidas has applied “Open Source” both internally and with external suppliers, from manufacturing partners to advertising agencies. But the principle has been most visibly — and successfully — put into practice in the way the brand collaborates with creators like Kanye West.

“We want that dialogue with like-minded people in fashion, music, art… because that leads to something totally new,” explains Torben Schumacher, general manager of Adidas Originals and Style, the lifestyle divisions where many of the brand’s creative collaborations are housed. “We’re not afraid to ask very open questions and get unexpected answers. I think the key is authenticity and that’s always been the thread with Adidas, from Run-DMC to Kanye. We now call this ‘Open Source’ but collaboration and our link to communities and culture and different creators has always been really important.”

One thing that’s certainly changed is the sheer volume of the brand’s partnerships with third parties. In recent years, Adidas has opened up to an army of collaborators from Kanye West and Pharrell to American artist Daniel Arsham and artisanal Japanese sneaker label Hender Scheme. Then, there’s Raf Simons, Rick Owens, Alexander Wang, Gosha Rubchinskiy, Palace Skateboards, Kolor, White Mountaineering, Porter, Wings + Horns, Mastermind Japan and BAPE, not to mention funky Swedish children’s brand Mini Rodini and Parley for the Oceans, an organisation committed to ending the destruction of marine life. And that’s on top of longstanding collaborations with Yohji Yamamoto and Stella McCartney.

“This willingness to collaborate is very modern. To a large degree this is what caused the massive revival of the brand,” says Fischer. “Whereas other footwear brands are extremely protective of their DNA, Adidas is going the opposite direction with collaborations that are more open-minded.”

Adidas even allowed Alexander Wang to play with core elements of the brand’s iconography, including its three stripes and trefoil logo. “The simple acts of turning the trefoil upside down or the stripes inside-out, for example, were our ways of illustrating what the collaboration is all about,” says Wang. “Everything about the collection stems from the idea of flipping brand conventions on their head… overturning commonly accepted rules and traditions of iconography and branding.”

“I think the danger becomes when you make something that becomes successful and you say: ‘Now it’s perfect, so I need to protect it.’ I don’t want to be perfect and make a big temple for Adidas. I want to be in dialogue,” explains Nic Galway, vice president of global design at Adidas Originals and the mastermind behind many of the company’s most popular models. “It has to be a genuine creative collaboration from the start, not just an endorsement.”

“Our open source approach provides a base for creativity,” adds Alegra O’Hare, global vice president of brand communications at Adidas Originals and Style. “There would be no creativity with a top-down approach.”

“Adidas gives me the freedom to create. They support individuality and creative expression and encourage you to push the bounds,” testifies Pharrell Williams. “It’s a relationship based on shared values and knowing that we have the ability to advance culture in whatever we do.”

In fact, before Kanye West partnered with Adidas, he worked with Nike, but found the company rigid in its approach to collaborations. When Nike refused to give him royalties on the sales of the “Air Yeezy” sneakers he designed with the brand, West responded by pulling the plug and signing a deal with Adidas. Announcing the move on Hot 97, a hip-hop radio station based in New York, he explained: “Nike told me, ‘We can’t give you royalties because you’re not a professional athlete.’ I told them, ‘I go to the Garden and go one-on-no-one. I’m a performance athlete’.”

According to StockX, a pricing guide and live marketplace for buying and selling sneakers, in December 2016, the average resale price of West’s popular Adidas Yeezy 350 Boost model was $992, up from $220 at retail.

“Looking ahead, we want to embrace the next generation. In the future, we might be empowering younger, lesser-known designers,” adds Galway. “Adidas doesn’t have all the answers. There’s a kid that knows what’s happening on the internet right now — and you’ll be out of date tomorrow. So, you have to open source. That was the change in thinking.”

Indeed, as consumer culture becomes increasingly fragmented and fast-moving, creating a proliferation of niche markets and a near-constant thirst for newness, “Open Source” has enabled Adidas to innovate and drive cultural relevance at a scale — and speed — the brand could never achieve alone.

“Speed to market is incredibly important,” says Fischer. “The market expects so much from a brand today. The attention span has become so short. Adidas alone probably releases new models three to four times a week.”

Speed is another key pillar of the company’s strategy. “Trends are happening a lot faster now and you want to be able to react quickly and bring your spin on a certain trend or happening or cultural moment, so you’ve got to be technically faster in your lead times, in your ability to launch products,” says Schumacher, citing the company’s “Speedfactory” in the Bavarian town of Ansbach, where Adidas is deploying new manufacturing processes like robotic cutting, digital knitting and 3D printing. A second Speedfactory is currently under construction near Atlanta, Georgia.

Embracing speed is not just about lead time optimisation, however. “It’s about learning to make decisions faster in constant interaction with the consumer,” explains Schumacher. Together, these elements enable Adidas to be more responsive to market demand, boosting productivity. Adidas expects 50 percent of its overall sales to come from “speed-enabled” products by 2020.

But it’s not all about speed and newness. Adidas has placed equal emphasis on reissuing retro models like its Stan Smiths, Superstars and Gazelles. “You want to be true to who you are and go back to your values. It’s also about celebrating the archives, the old as much as the new,” says Schumacher. Adidas sold 15 million pairs of its shell-toed Superstars in 2015, boosted by aggressive marketing and a collaboration with Pharrell. Last year, the Superstar was the top-selling shoe in the US. “Cultural equity is very difficult to quantify, but it no doubt drives commerce,” says Gary Aspden, a branding expert and consultant to Adidas.

The third pillar of the company’s strategy is a new approach to geography that’s more in tune with how consumer culture is created and disseminated in today’s rapidly urbanising and hyper-connected world. “These days, cities are more connected than the countries,” explains Galway. “Like, the NMD wasn’t right for China or the US on paper. But in reality, it was right for sneakerheads and they live in key cities. So, we think about what the mentality of a key city looks like rather than a country.”

“Key cities are everything,” he continues. “It’s where culture comes to life. It’s where the old codes get broken down and the new codes come to life. Every youth generation wishes they lived in those cities and they all reference those cities. It’s always shifting, but today it’s New York, Tokyo, Paris, London, Los Angeles, Shanghai, Seoul… They’re really shaking up the establishment.”

In August, Adidas reported strong performance in the second quarter of 2017, with revenues growing 19 percent on a currency-neutral basis. Momentum was especially strong in key markets like Greater China and North America, where revenue grew by 28 percent and 26 percent, respectively. As a result, the company raised its outlook for the year.

“The big question will be, can they continue at that pace? Can all these new initiatives continue to work as well for them? What I’m impressed with so far is that I don’t feel like things are getting any slower,” says Fischer.

‘Culture in Every Sport’

So far, the results of the company’s strategy have been most visible in its lifestyle divisions, like Adidas Originals, which, last year, grew sales by more than 80 percent in the US market. But Adidas is now bringing elements of the approach to its core performance categories, which sit at the heart of the brand and constitute a significant chunk of sales revenue.

“There’s culture in every sport. There’s moments beyond the competition in every sport,” says Galway. “I guess we have stopped drawing that clear line: this is just sports and that’s just fashion.”

The shift began with Adidas Football, one of the company’s core performance divisions, which earlier this year unveiled a multi-season partnership with Gosha Rubchinskiy. “The pure sport kids don’t live in a bubble anymore. They know Gosha and Palace and Kith. They’re in a world where music, art, design, fashion and sport have all blurred together,” explains Sam Handy, vice president for design at Adidas and Adidas Football creative director, who oversees the partnership with Rubchinskiy. “My personal feeling is that smartphones have changed things. The way that young people now see their influences through a feed blends things together in their minds.”

“I like the project with Adidas because it’s not just a fashion project,” says Rubchinskiy. “I like to work with real sports like football. It’s the first time for Adidas Football to collaborate with a designer. I’m interested in skaters but also other cultures. Football fans also have an interesting style.”

“The idea of collaborating with great partners from the fashion world has become fairly standard, but to bring that logic to a high-performance category — I believe this is actually the game changer for Adidas,” adds Handy. “It was a big debate within the company, but it’s resonating with consumers. When we announced that [footballer] Paul Pogba was joining the team, we didn’t use a video of him taking a free kick. We showed him dancing with [rapper] Stormzy. It’s a different approach. I would like to see it spread.”

I guess we have stopped drawing that clear line: this is just sports and that’s just fashion.

“I’m not interested in the evolution of fashion collaborations. I’m interested in the evolution of sport in the mind of young consumers,” continues Handy. “I don’t know the answer; the kids know the answer. The most important thing about ‘Open Source’ is dialogue with the people who buy your product.”

But Fischer sees risk. “To a certain degree, this is what killed Puma a decade ago. They lost their significant to sport. What you see right now with Gosha and Adidas Football seems like a strong collaboration, because it’s genuine. But it’s still a big risk to go down the lifestyle route with your most important sports categories.”

“If you look at the Ultra Boost, it was marketed as a running shoe. But naturally it made its way into lifestyle because Kanye wore them on stage. But it’s a slippery slope. For now, I don’t think Adidas will make the same mistake as Puma, as they’re very aware. But they need to keep a close eye.”

Disclosure: Vikram Alexei Kansara and Christopher Morency travelled to Herzogenaurach as guests of Adidas.

This article appears in BoF’s latest special print edition: “Generation Next”. The issue is available for purchase at shop.businessoffashion.com and at select retailers around the world.

Did you know that BoF Professionals receive our print issues first? Annual BoF Professional memberships also include unlimited access to articles, exclusive analysis, invitations to networking events and the members-only app. Not a BoF Professional? Subscribe here.