NEW YORK, United States — At a news conference Monday morning, livestreamed on YouTube and emceed by the actress Anne Hathaway, Valentino Garavani and long-time business partner Giancarlo Giammetti unveiled the Valentino Garavani Virtual Museum, a downloadable desktop application that showcases almost five decades of the designer’s work, drawing on a database of over 180 videos and 5000 images, including Valentino’s original sketches. A fashion first, the digital museum invites users to navigate a series of immersive galleries, organised by theme and rendered in 3-D, that in the physical world would stretch over 10,000 square meters.

Funded entirely by Mr. Giammetti and Mr. Garavani at a reported cost of several million dollars, the virtual museum, which is free to access, serves no direct commercial purpose — the duo no longer have a financial stake in the Valentino business, which is owned by private equity firm Permira — and exists for the sole aim of securing the designer’s legacy.

But the Valentino museum launch comes at a significant moment for the industry. Public interest in fashion exhibitions is surging. This summer’s record-breaking Alexander McQueen exhibition at The Metropolitan Museum of Art attracted over 650,000 visitors. Meanwhile, big luxury brands like Louis Vuitton, Chanel and others are moving to control and communicate their heritage by staging large-scale exhibitions at major museums in emerging markets. Gucci has even opened a private museum of its own in the heart of Florence.

While lacking some of the inherent experiential value that comes with exploring a physical space, the Valentino virtual museum offers obvious advantages in terms of cost and reach — no small points in the context of today’s globalised and uncertain economy — and the initiative’s strengths and weaknesses are sure to be examined closely by other fashion brands in the weeks and months to come.

Having previewed the Valentino Garavani Virtual Museum in the days prior to launch, BoF sat down with Mr. Giammetti just before the press conference to discuss the vision behind the world’s first digital fashion museum.

BoF: Why did you decide to make this museum a digital experience instead of a physical one?

Giancarlo Giammetti: I’m passionate about virtual tours. I remember years ago going online to the website of the Barnes Foundation. I was fascinated by this virtual tour, which was a camera going around the rooms of the gallery. You could move and focus on paintings. This was always in my mind. And when we started to think about what to do with this huge archive of forty-seven years, which was quite well organised, I wondered how to make it available and how to keep it together and also how to keep it as a memory for ourselves. So the idea of a virtual museum was born.

We have a small museum in France, but it’s very small. There are not hundreds of dresses there. Also, it’s not in Paris, but about one hour from Paris, so it’s much more difficult to bring people there. I respect real museums very much. I think, especially in this country, fashion museums are doing an amazing job. But for one designer to have his own museum and be sure that it will live forever and not one day look dusty and instead keep fresh — how will this happen? Digital is also the language of today, so whomever will come after us can still see it, because it’s something modern, not something related to a model of the past.

BoF: We understand you worked with the digital agency Novacom Associés-Paris, as well as the architects Patrick Kinmonth and Antonio Monfreda, to bring the museum to life. What was the brief you gave them?

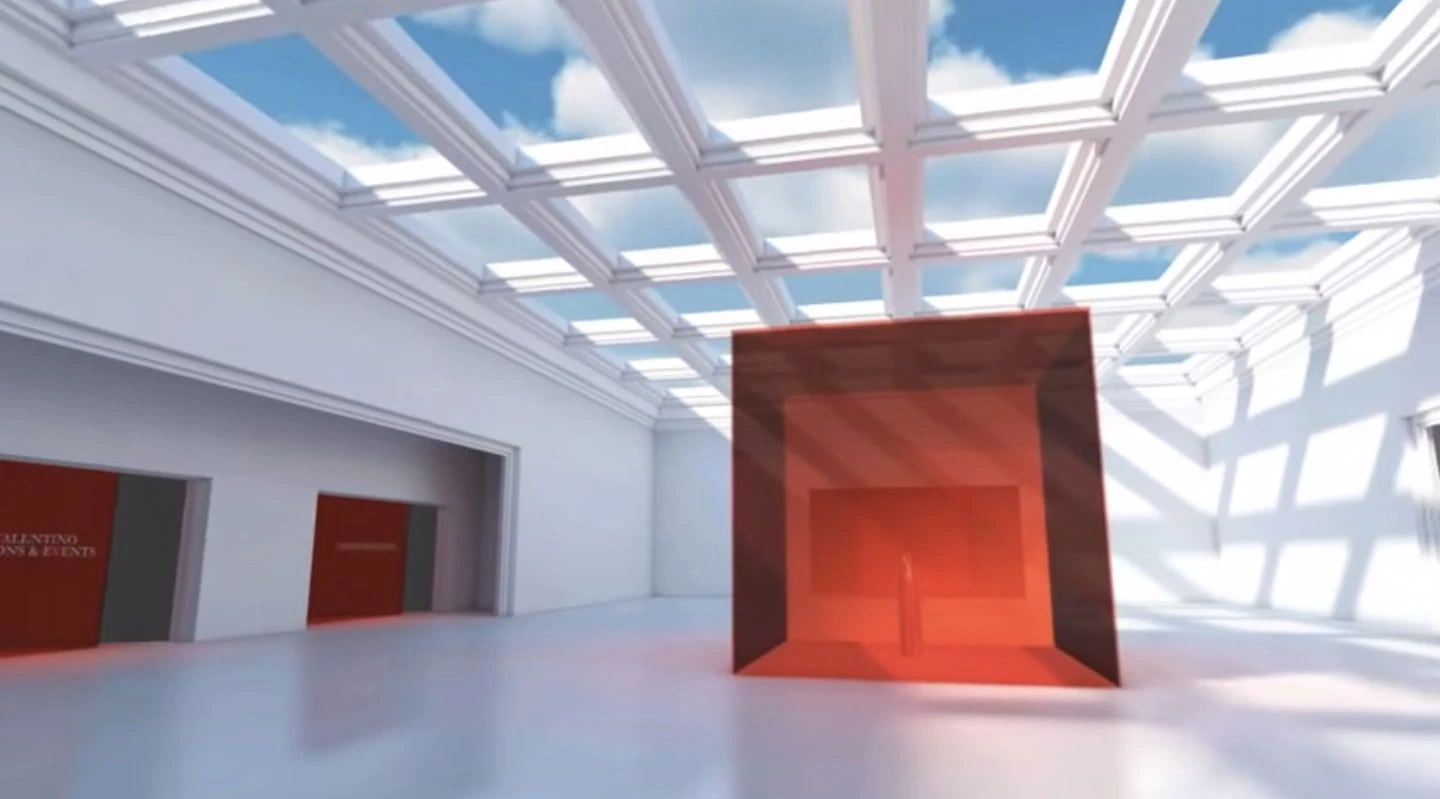

GG: The brief was, first, to create the architecture. I wanted something very modern, very simple. But I wanted to keep the idea of a room and have a blue sky with clouds moving to simulate the breeze of Rome, so we have skylights. As it’s an archive, of course you want to see the dresses, you want to see the photography, you want to see the people. There is a master class [where Valentino explains his creative process]. There is an interview in which I describe our adventure together. I wanted to keep it something classic, but bring it to a different reality. In the end, we wanted a real museum, but in a virtual way.

BoF: The museum features an impressive array of content. What is your favourite part?

GG: My favourite part is “Very Valentino” where you see five decades of clothes. There is one dress, for example, and behind that you see Monica Vitti wearing the dress in L’Avventura, the movie by [Michelangelo] Antonioni. And then you see a picture by Helmut Newton of Valentino and Monica and Antonioni in the Caffé Greco in Rome, along with the original Valentino drawing of the dress. All this together — this is the world of Valentino, this is the world of that dress. For every garment, you can see a video — if there is a video, because don’t forget video began in the 1980s — and the original drawing, press clippings, advertising, all linked together.

BoF: Alongside the museum itself, you have launched a presence on Facebook, Twitter and YouTube. How will these channels complement the experience?

GG: On Facebook, there were so many Valentino Garavani fakes, like for every celebrity I would imagine. I wanted to create [an authentic Facebook presence] myself, so I started with The Real Valentino Garavani. It was more for our friends; it was not huge, just four thousand people. But I started to put a lot of material there; of girls, models, press. And then it was normal to move to Facebook for the museum and then to Twitter.

BoF: In terms of the museum, one thing we haven’t talked about as yet is the audience. Who are you trying to reach? Are there people you hope to reach with a digital museum who may not have visited a physical archive?

GG: Yes. That’s why you get the application for free. We didn’t want people to have to pay to get into the museum. We didn’t want any sponsors. All the investment is [from] Valentino and myself. In 2008 or 2009, we did a show at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris. It was beautiful to see all these young people sitting on the floor and drawing. That’s who we want to reach here. But Les Arts Décoratifs is small. This can be huge.

BoF: You mentioned as we were sitting down that this was your first experience working in digital. Can you describe what that experience has been like and one lesson that you have learned?

GG: It never stops! When I started working on this, I thought when you have finished you take a break. You have done it and it’s there. But no! We want to evolve it. I’m already thinking that the master class of tomorrow will be done by an important journalist, or I will have somebody witty — I already have somebody in mind — who writes a blog, so I’ve learned that it seems easy, but it’s not.

OUR THOUGHTS:

Expectations? When we first heard that the legendary Mr. Valentino and Mr. Giammetti were launching a virtual fashion museum, we were excited. In the context of the physical exhibitions currently being staged by a number of luxury brands, here was a new digital format that offered both practical advantages and new creative possibilities. Expectations were high.

First impressions? As soon as you enter the museum, the ambitious nature of the undertaking becomes clear. The digital architecture is stately and there is a vast amount of rich content to explore. But the videogame-like experience is a far cry from the standards of popular gaming titles and the 3-D graphics feel dated. One of the major advantages of a virtual museum is greater accessibility and one of the key audiences the experience aims to reach are young people, who are highly mobile and constantly bombarded with a vast array of media experiences competing for their attention. Therefore the decision to create a downloadable desktop application rather than a web app that can be easily enjoyed across devices and during quick bursts of media-snacking is unfortunate. Of course, this choice stems from the choice to apply the metaphors of a physical museum to a digital experience. It’s one thing to make physical museums digitally accessible à la Google Art Project. But when creating a digital museum completely from scratch, why follow the conventions of a physical gallery?

Most potential? Conceptually, the core idea of a digital fashion archive is strong. Not only does a digital experience have the potential to be far more accessible and cost-effective than a bricks-and-mortar museum, but the flexibility of digital media enables users to more easily explore the web of interesting relationships and interconnections between pieces of archival content. For each garment there is a rich back-story of videos, editorial images and sketches.

What’s more, unlike a physical museum that has certain fixed properties, a virtual museum can be updated at the pace of a blog, an opportunity Mr. Giammetti appears eager to seize. Indeed, if Mr Giammetti and Mr Garavani commit themselves to the kind of constant experimentation and rapid innovation that digital allows, they have the opportunity to create something that no fashion house has yet achieved: a living and breathing archive that’s globally accessible and ever-evolving. This is a powerful way to secure the legacy of one of the world’s greatest fashion designers.

What’s missing? The virtual Valentino museum is a closed system, isolated from the social web. None of the archive’s rich content is sharable and there is no integration with leading social platforms like Facebook and Twitter. This is a missed opportunity to spark conversation amongst fans, and indeed to drive more people to explore the museum, especially after the initial media buzz has faded.

Furthermore, a visit to the virtual Valentino museum is a solitary experience, where it’s impossible to see, be influenced by or interact with fellow visitors. One of the most powerful ways to create the kind of digital archive that Mr Giammetti envisions — never dusty, always fresh — is to harness the energies of visitors. For example, why not let users curate a selection of their favourite dresses, remix them with other archival content and share this record of their experience, both within the museum and beyond? The possibilities are endless.

But perhaps the single most powerful and forward-looking thing that Mr. Giammetti and Mr. Garavani could do to unlock the creative potential of their substantial archive is to develop an Application Programming Interface or API. Technology companies like Google, Facebook and Twitter often publish APIs — interfaces that enable software to interact with other software — making their platforms available to external developers who can leverage them to build new experiences and applications. For example, in August, luxury retailer Bergdorf Goodman used the Google Maps and Instagram APIs to create Shoes About Town, an interactive map featuring geo-tagged images of covetable footwear. In a similar way, a Valentino museum API could give select developers access to the vast amounts of content currently housed in the digital archive — dresses, images, videos, text — with which they could build new experiences and applications to add to the virtual museum project and bring the designer’s legacy to life in previously unimaginable ways.

In Digital Scorecard, BoF’s editors review the most innovative digital initiatives from across the world of fashion.