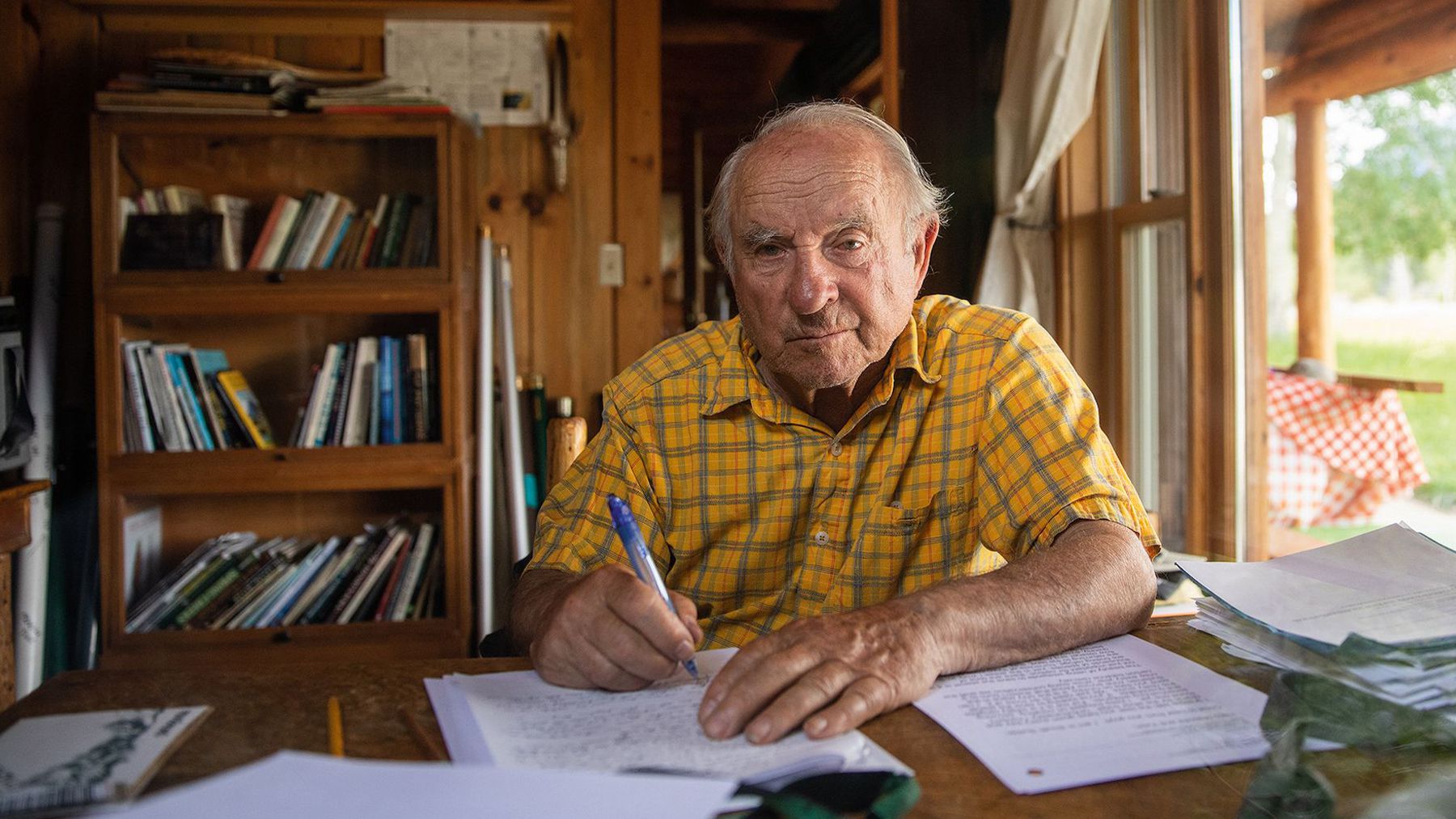

Patagonia founder Yvon Chouinard may be the world’s most reluctant billionaire.

For 50 years, the rock climber and environmentalist has tried to chart a tricky course, becoming a poster child for an unconventional form of capitalism that seeks to balance profit and purpose.

Patagonia is now one of the world’s most successful outerwear brands, with sales of its fleeces, windbreakers and flannels topping $1 billion a year, according to The New York Times. But it’s also blazed a trail for responsible business practices; the company has donated 1 percent of all sales to environmental groups since the ‘80s and was among the earliest companies to qualify for B-Corp sustainability certification. Patagonia’s mission statement: “We’re in business to save our home planet.”

Now the 83-year-old Chouinard has found a way to sustain and push that commitment even further: he’s giving the company away. Going forward, almost all of Patagonia’s shares will be held by a non-profit organisation tasked with reinvesting its profits (projected at some $100 million a year) in fighting the climate crisis.

“Earth is now our only shareholder,” Chouinard wrote in an open letter posted on the company’s website.

It’s a near-unprecedented move that sets an intriguing new benchmark for responsible business models. It also points to just how broken the existing system remains.

Chouinard’s bid to recast capitalism in service of the climate comes at a time of turmoil for corporate crusaders. Though the notion that businesses should consider people and planet alongside profit is increasingly mainstream, the extent to which companies and investors are actually living up to lofty commitments to incorporate this into spending plans and strategies is under increasing scrutiny.

In announcing his decision to structure his succession plan as what amounts to a massive donation, Chouinard also took down other, more traditional, exit options.

The founder could have sold the company and donated all the money, but then there would be no guarantee the new owners would continue to operate in line with Patagonia’s existing values. A public listing was a non-starter. “What a disaster that would have been,” Chouinard wrote in his open letter; public companies face too much pressure to prioritise short-term profits over everything else.

“There were no good options available. So, we created our own,” Chouinard said.

Here’s how the new structure works: while Patagonia will continue to operate as a for-profit company, it will be owned by a combination of a trust and non-profit organisation.

The trust, which will control the company’s voting shares (two percent of the total), will be responsible for ensuring Patagonia continues to balance profits while serving the planet. The non-profit will own the rest of the company, receiving all profits that are not reinvested in the business as an annual dividend to be spent fighting the climate crisis.

In transferring their ownership, Chouinard and his family have given away shares worth about $3 billion, according to The Times, which was first to report the news. Even more unusually, the ownership transition was not organised for tax efficiency (often companies or individuals stand to receive significant tax benefits from outwardly altruistic initiatives). The restructuring will in fact cost the Chouinard family about $17.5 million in taxes, The Times reported.

Coming up with a structure that would both protect Patagonia’s current operating model and guarantee ongoing funding for environmental causes took two years, Patagonia CEO Ryan Gellert said in a statement.

Whether this new structure can inspire broader change remains to be seen. “This is not “woke” capitalism. It’s the future of business,” Patagonia chair Charles Conn wrote in Forbes.

It certainly offers a new template that might previously been unimaginable for many in the business world. Chouinard has form in turning radical acts into established models; Patagonia’s practice of donating one percent of sales each year is now formalised in the 1% for the Planet movement and has nearly 5,000 business participants.

But companies that are publicly owned or lack shareholders with values as aligned as the Chouinard family are unlikely to be able to follow Patagonia’s radical restructuring – the approach is unique and not easily replicable for conventional businesses.

Patagonia must also prove that this new model can deliver a balance between profit and purpose – and contend with the tension that still exists between the sales that fuel its profits and their contribution to the very problem it is fighting to address.

For more BoF sustainability coverage, sign up now for our Weekly Sustainability Briefing by Sarah Kent.