Who, exactly, is responsible for the “loss and damage” caused by climate change? At this year’s UN climate summit, the divide between the Global North and the Global South, where poor countries are demanding compensation, broke wide open with big implications for the fashion industry.

Fast-fashion, sportswear and “affordable luxury” brands based in the Global North typically source their products in some of the world’s most climate-vulnerable countries such as Indonesia, Vietnam, Cambodia, Bangladesh and Pakistan, and are no doubt responsible for a share of loss and damage there. Quantifying the impact with precision is notoriously difficult but from the vast volumes of production inputs — cotton, polyester, dyes, water, carbon-based energy — we know this share is enormous.

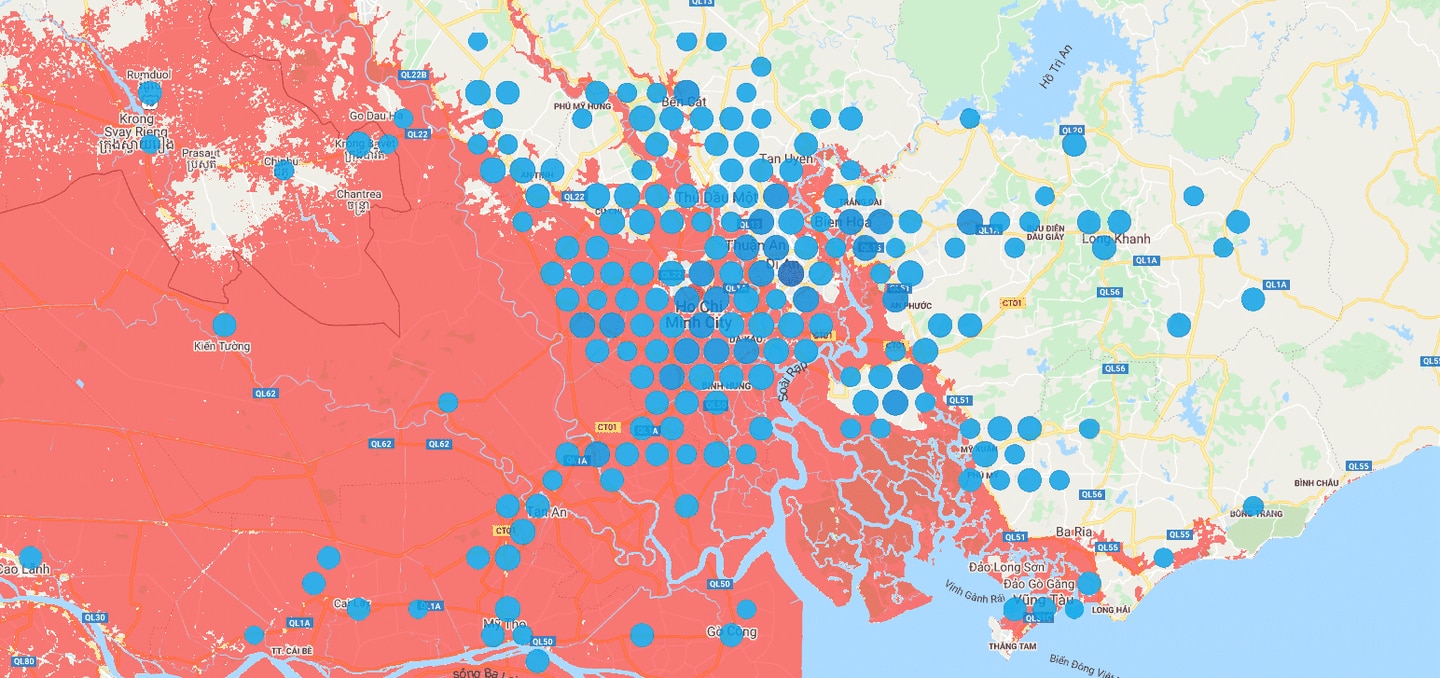

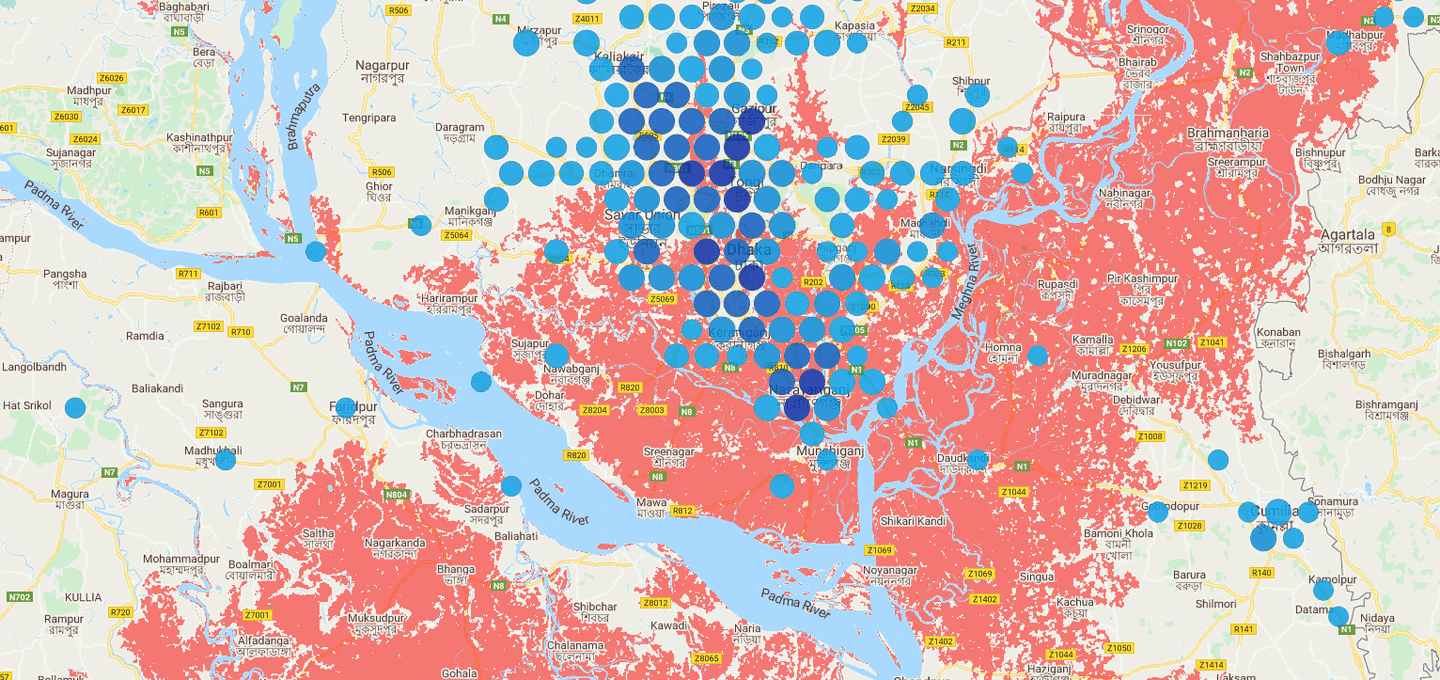

The fashion industry has largely framed its climate responses around environmental issues, such as recycled fabrics, water usage and greenhouse gas emissions. But the industry is ignoring climate impacts that are directly and dramatically affecting apparel suppliers and their workers. Last year, we released analysis showing how projected increases in flooding, extreme heat and humidity will affect workers and production in some of fashion’s top sourcing hubs: Bangladesh, Cambodia and Vietnam.

Life, let alone work, will become very difficult in these areas and a dozen other hotspots that brands and retailers depend on for their production. Alarmingly, these risks are not part of the fashion industry’s sustainability plans because brands and retailers have spent decades keeping groups such as factory workers, unions and regulators at arm’s length. And as a result, costs and risks are pushed beyond the boundaries of the firms’ legal liability. In fashion, these problems become externalities that belong to workers, manufacturers and their governments.

Fashion’s business model isn’t built to solve complex problems like those posed by climate change. In fact, many argue that the model is designed to avoid them.

Relief and remedy must include cooler workplaces and industrial areas, renewable and reliable energy, flood mitigation, work routines that protect workers’ health and the right to organise unions and bargain for these things. And in Bangladesh — now the number two producer of European apparel — it will have to include the basics: a social protection system, building codes and maximum workplace temperatures.

For apparel workers, relief will also mean wages that allow them a chance to get ahead of soaring food costs, lack of drinking water, the rise of heat-related illness and more.

This kind of change requires redistributing costs and risks, including those of climate breakdown, away from workers and their employers and back towards brands. Or, in the language of COP27, from the producing countries of the Global South to their Global North trading partners.

We see two new forces attempting to move the industry in this direction. The first is regulation, most importantly the European Commission’s new due diligence requirements and pro-worker trade policy in the United States. New rules could mean legal liability by brands and retailers for violations of environmental and human rights standards along their supply chains.

The second is the global cooperation on display in campaigns like #payyourworkers and organising by apparel and footwear suppliers in schemes like the Sustainable Terms of Trade Initiative. These efforts start from a new premise: climate breakdown and the damage it is bringing are not a series of technical problems for fashion’s countless working groups to debate; they are, at their root, problems of power and mal-distribution.

The part of the industry that is not serious about its environmental and social impacts will have to be swept up by new rules about due diligence and legal liability for adverse environmental and social impacts on workers.

And the fashion brands and retailers serious about mitigating climate breakdown in Bangladesh, Cambodia, Honduras and Vietnam — as with the Accord signed in Bangladesh by unions and global firms after the Rana Plaza crisis — must commit to stay, negotiate and adapt.

Those commitments must be based on evidence-based answers to a new, broader set of questions about climate breakdown: How much of fashion’s annual production will be lost to extreme heat and flooding under different climate scenarios in 2030? In 2050? What about losses in export earnings and national income? What is the likely loss and damage in terms of jobs and income, workers’ health and their food security? What will relief and remedy costs look like and who will pay for it?

Fashion can start collecting and sharing data to help measure these impacts now. Tackling these questions is only possible when the industry recognises that it needs to negotiate a new future.

Jason Judd is executive director and Sarosh Kuruvilla is academic director of Cornell University’s Global Labor Institute. The next iteration of the GLI’s analysis is due to be released in early 2023.